Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the soon-to-be-published National Association of Scholars report, Rescuing Science. It has been edited to align with Minding the Campus’s style guidelines and is cross-posted here with permission.

Indirect costs are a hot topic right now, set off by the Trump administration floating a proposal for the National Institute of Health (NIH) to cap indirect costs rates at 15 percent. Prior to that, indirect costs were one of those bits of research funding arcana that no one had ever heard of. Now, everyone is talking about them.

Here is the issue. Indirect costs are surcharges on research grants that ostensibly cover a university’s overhead expenses for supporting a research project. These can include administration, compliance, building maintenance, and equipment depreciation, Indirect costs are assessed as a percentage of the direct costs of a research grant, which are the costs to support the research itself: salaries of scientists, students, and support staff, equipment, supplies, travel, publication charges, that sort of thing.

Presently, the national average for indirect costs rates is 53 percent of direct costs, although these can range up to 70-80 percent of direct costs at certain universities. In FY2023 (Table 1), federal funding of university research grants was about $60 billion, which covers both direct and indirect costs. A 53 percent indirect costs surcharge on $60 billion amounts to about $20 billion. Add to that another $5 billion from state and local governments to support university research and about $6 billion plus change from businesses, and there is an additional yield of $4 billion in indirect costs revenues. Add all that together, and universities nationwide are able to tap into a $24 billion revenue stream for overhead costs. Cutting indirect costs rates to 15 percent would reduce that revenue stream to about $9 billion, a 64 percent reduction.

Table 1. FY 2023 R&D expenditures by source.1 Sources tagged with asterisks are subject to indirect cost assessments.

(Millions of dollars)

| Source | FY2023 Expenditures |

| All R&D expenditures | $108,841 |

| Federal R&D* | $59,679 |

| State and local R&D* | $5,447 |

| Institutional R&D | $27,702 |

| Business* | $6,230 |

| All other | $9,782 |

You can see why universities would object, but harder to see why scientists would. The FY2025 research allocations are reduced by about $7.5 billion (Table 2), about 95 percent of which is in defense research. For the NIH, National Science Foundation (NSF), Department of Energy (DOE), and Veterans Affairs, there were no changes in research funding from FY2024 to FY2025. There were modest reductions in the research allocations for NASA, the USDA, Department of Commerce, and the Department of the Interior, less than 4 percent.[2]

Table 2. All federal expenditures for research and development by federal agency for FY2024 and FY2025. These expenditures support both intramural and extramural research.2 Sources tagged with asterisks are agencies where there was no change in allocations from 2024 to 2025.

(Billions of dollars)

| Source | FY2024 R&D | FY2025 R&D | FY2025 to FY2024 | |

| Defense | $109.22 | $102.12 | -$7.10 | |

| HHS* | $45.48 | $45.48 | $0.00 | |

| Energy* | $12.74 | $12.74 | $0.00 | |

| NASA | $12.41 | $12.40 | -$0.01 | |

| NSF* | $7.40 | $7.40 | $0.00 | |

| USDA | $3.52 | $3.42 | -$0.10 | |

| Commerce | $3.85 | $3.70 | -$0.15 | |

| Interior | $1.26 | $1.17 | -$0.09 | |

| Veterans* | $1.70 | $1.70 | $0.00 | |

| Others | $3.26 | $3.25 | -$0.01 | |

| Total | $200.84 | $193.38 | -$7.46 |

At the current rate of 53 percent indirect costs, universities can skim about $22 billion of that in overheads (Table 1). Cutting the rate to 15 percent will reduce universities’ take to $8-9 billion. That’s the bad news for universities. If there are no reductions in overall research spending, as is the case for the DOE, Department of Health and Human Services, and the NSF, this is good news for researchers. Reducing indirect costs rates to 15 percent will increase the funds available for direct costs—the money that funds the actual research work—by about $14 billion.

In 2017, the first Trump administration attempted to reduce the NIH’s indirect costs rates to 10 percent. Furious doom-mongering followed. The President of Johns Hopkins University—indirect costs rate of 62 percent—declared the change would deal a “staggering blow to the nation’s vital interest.” The president of the Association of American Universities (AAU), a lobbying group for university administrators, jumped in to assert that the proposal would “literally turn out the lights in labs”. The Trump budget proposal failed, Congress increased the NIH budget by roughly nine percent, indirect cost rates remained high, and indirect cost revenues streaming to universities from the NIH were boosted by about $550 million. The current proposal to cap indirect costs rates to 15 percent has elicited a similar negative reaction.

To be clear, overhead costs are a legitimate expense for doing research. What is unclear is the correspondence of actual overheads to the monies generated through indirect costs. Clarifying that turns on two questions. First, what is the actual impact of a reduction of indirect costs on a university’s finances? Second, are the current high indirect costs rates appropriate for the financial burdens universities undertake for supporting research? I will explore the second question in a separate article.

To answer the first question, I turn to a case study, focusing on the finances of a typical mid-level research university that has a robust research program. I will not identify the university here. Let us call it X University, or XU. Like any organization, universities compile regular financial reports and audits, usually through private accounting firms. The XU case study is derived from XU’s 2023 financial report. I add a disclaimer: I am neither an accountant nor an auditor.

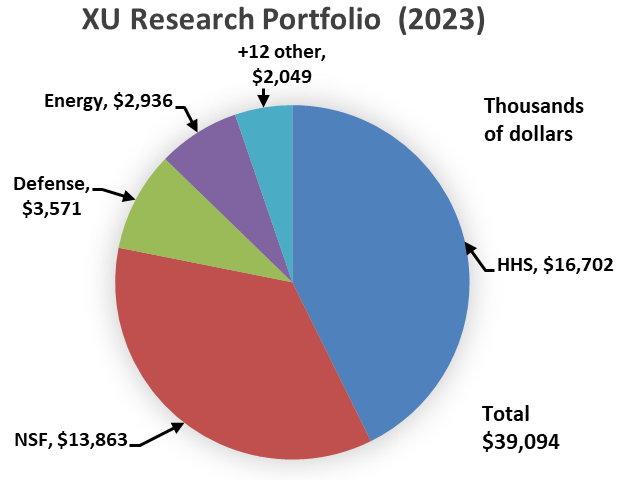

Figure 1. Research portfolio of XU for 2023. Source: XU financial report for FY2023.

(Thousands of dollars)

XU’s research portfolio is supported by about $39 million of annual revenues in grants and contracts from sixteen public and private sources (Figure 1). Roughly 95 percent of that is drawn from four federal agencies. Two (Health and Human Services, which hosts the NIH, and the National Science Foundation) account for roughly 78 percent of XU’s total research portfolio. Two other federal agencies (the Departments of Defense and Energy) account for the additional 17 percent. The remaining five percent comes from twelve other sources, both government and private.

XU assesses indirect costs at a comparatively modest rate of 49 percent of direct costs (the national average is 53 percent). This yields indirect costs revenues of about $13 million. A reduction of indirect costs rates to 15 percent would reduce XU’s indirect costs revenues to $5 million, a shortfall of about $8 million. Assuming true overheads of $13 million, XU would have to make up the shortfall from some other source. Could it do so?

Table 3. XU total assets and liabilities for FY2022 and FY2023. Source: XU financial report for FY2023.

(Thousands of dollars0

| FY2022 | FY2023 | Change | |

| Assets | $4,031,067 | $4,263,542 | $232,475 |

| Liabilities | $1,228,979 | $1,227,282 | -$1,697 |

| Net assets | $2,802,088 | $3,036,260 | $234,172 |

In 2022, XU listed its net assets (assets minus liabilities) as $2.8 billion (Table 3). In 2023, those grew to $3.0 billion, an increase of about $234 million. The predicted shortfall of $8 million in indirect costs revenue amounts to three percent of this increase.

Table 4. XU operating revenues and expenses for FY2024 to FY 2025. Source: XU financial report for FY2023.

(Thousands of dollars)

| FY2022 | FY2023 | Change | |

| Operating revenues | $1,157,869 | $1,287,098 | $129,223 |

| Operating expenses | $1,089,983 | $1,171,328 | $81,345 |

| Net | $67,886 | $115,770 | $47,884 |

In both 2022 and 2023, XU’s operating revenues exceeded operating expenses (Table 4). From FY2022 to FY2023, XU’s operating surplus increased by about $48 million. The $8 million shortfall in indirect costs revenue amounts to about 17 percent of the increased surplus.

Whether the indirect costs shortfall could be absorbed in operating expenses depends upon XU’s administrative priorities. Salaries are usually the largest item in any organization’s budget. University administrations are usually the largest consumer of salaries, which have become bloated in recent years. Perhaps the $8 million shortfall in indirect costs could be covered by trimming administrative positions or salaries?

According to XU’s IRS Form 990 for 2023, the compensation for XU’s top paid administrators totals to $17 million. Form 990 also lists more than 1,100 employees with compensation greater than $100,000 (Form 990 does not distinguish between administrative and faculty employees). XU also lists more than 70 administrative lines, which carry salaries up to $50,000-$100,000. Perhaps $8 million could be found through cuts in administrative staffs?

Other administrative choices are open for XU to cover the expected shortfall. From 2022 to 2023, for example, XU increased its holdings in buildings and equipment by about $115 million. XU also sits on an endowment of roughly $5 billion. Could $8 million be squeezed out of that? Probably.

Thus, there does seem to be sufficient capacity in XU’s finances to absorb the indirect costs shortfall through adjustments in salaries, the number of administrators, and slowing real property acquisition and capital projects. It is difficult to square this with the apocalyptic language swirling around reductions of indirect costs.

All of these calculations assume that the current 49 percent indirect costs rates actually cover overheads. There is reason to believe that indirect costs rates for universities are too high. Indirect costs rates in the United States are 2-4 times higher than for other countries with national science programs. Private R&D and charitable foundations usually get by with considerably lower overheads. Charitable foundations typically impose their own caps of 10 percent on grants they give to universities. This will be the topic of a separate article. There is a deeper cultural issue at play, which I raise now.

The core mission of a university is teaching and research. Prior to World War II, universities funded their core mission through institutional funds, philanthropy, and tuition. Federal support for education and research was minuscule. After World War II, the federal government moved to federalize university teaching and research, which has been doubling roughly every seven years for more than seven decades. Federal support of teaching and research has now grown to the point that the federal government is the major funder of universities’ core mission. We have come to the point that universities look upon federal revenue as an entitlement, upon which they have become utterly dependent. The hysterical reaction to any proposal to wean universities off this sense of entitlement is evidence of this dependency.

Cuts in indirect cost reimbursements signal to universities that it is time to step back from that entitlement mentality and take more responsibility for funding their core missions: to return to the independence they enjoyed prior to World War II. The example of XU indicates that they are more than capable of doing so.

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Image: “NIH Campus: North” by NIH Image Gallery on Flickr

The cut to 15% is even less than you are making it out to be. Currently, it’s 53% (median) of modified direct total costs. With the key word being “modified”. Many costs (tuition, equipment) are not part of modified costs. I’ve seen statistics putting the current rate at closer to 30%, so these universities would have to deal with something like half of indirect costs that they are currently dealing with. Most diversified places, like your university X, will complain, but manage.

There some “research institutes” that are wholly dependent on government funding, usually NIH funding. Those will probably not survive.

Completely disagree with this comment:

>

The current research model was designed in something like 1947 to win the Cold War, which we did in 1990. And now we have this massive Federal funding from a government which is essentially broke.

<

The USSR never had technological superiority over us (or even parity). China, unfortunately, is more than capable of achieving this, with their Wilhelmian governmental organization (and recall the the Second Reich almost defeated the coalition of Russia, Britain, France and the US). This calls for more research monies to be allocated for AI and robotics and laser weapons.

One word: Sputnik.

That was October, 1957 and what a lot of people forget about the space race is that it actually was the ICBM race because an ICBM is just a sub-orbital flight with a survivable re-entry vehicle. (A MIRVed ICBM is one with “Multiple targeted Independent Reentry Vehicles” — or multiple nukes that can be independently targeted.)

The Nazi rocket program was in Peenemünde, which was in East Germany and while we carted off as much as we could quickly grab (along with “operation paperclip”) they got the majority of the research. This came to play in Vietnam where their rockets were shooting down our airplanes.

The Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb on August 1949, and a Hydrogen Bomb in November of 1955. In October of 1961 they touched off the largest bomb that the world has ever seen, the 50 Mt Tsar Bomba.

Khrushchev bragged that they were squeezing out ICBMs like sausages, he lied, but we thought that their capabilities were far greater than they were.

The first student loans were the National Defense Student Loans which were intended to help students majoring in fields such as mathematics, science, and foreign languages.

I don’t disagree about your concerns regarding the PRC, but we really ought not have their army officers in our grad programs learning our research…

You’re spot on about the connection of federal science funding and Cold War geopolitics. See Audra Wolfe’s fine book Freedom’s Laboratory for an excellent account of that. Also, spot on about the expansion of science funding post Cold War, which has gone on expanding exponentially (doubling time of about seven years). Scientific knowledge has not doubled every seven years, however, even though one could argue that the simulacrum of science has. It’s almost like Head Start, a spending program that exists to spend money.

I differ with you slightly about your characterization of Soviet science, however. Again, I’d point to Simon Ings’ book Stalin and the Scientists, as well as Richard Rhodes’ excellent histories, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, and Dark Sun, about the hydrogen bomb. Soviet science was certainly beset with difficulties, but lack of scientific capability was not one of them.

The obvious point to make is that “overhead” is set in order to keep the enterprise or organization functioning, if the market is competitive (which university research is, given there are typically hundreds of labs capable to performing a particular research project). As an example, when I go to a car dealership, they have a labor charge, typically a factor of two over what they pay the person actually doing a labor. I am paying for the tools, the administrative staff, and also profit. I don’t get to go and say that I should only pay 10% of what they are paying the person actually fixing my car.

Now, the question becomes will we actually get more “product” by paying less in overhead. Almost certainly not–universities will adjust because they still have fixed costs to cover. They may admit fewer grad students or fund fewer post-docs (these are the people who actually “fix the car”), and they will charge more for these services in one way or another, or supply less “product.” Now, it might be argued that universities have increased their support staff and ancillary staff way more than is defensible. That is another discussion (and a useful one also).

Another way to look at this is if universities were making monopolistic or oligopolistic rents, individuals or firms would be creating their own institutes and competing for government contracts and could out compete them and get the contracts. We will never see this because the aforementioned post-docs and graduate students are working for wages well below their market value (hence the trend towards unionization on college campuses for these groups) since they are working for a degree also, and can enter into the academic hierarchy (harder and harder to do–another impetus for unionization).

I personally think we should have the staff scientist method of organization, as in Europe, and only train enough graduate students to fill available positions. This means your comparative lit department is going to lose ninety percent of their students. I can live with that. But our current process of having multiple bodies for every possible position creates a problem and their are even theories that elite overproduction has lead us to our current societal structure—see https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2024/nov/30/the-deep-historical-forces-that-explain-trumps-win!

“Another way to look at this is if universities were making monopolistic or oligopolistic rents, individuals or firms would be creating their own institutes and competing for government contracts and could out compete them and get the contracts.”

The current accredition system precludes this — it would be a very different world if think tanks could offer degrees and receive Federal funds. it IS an oligopoly — you can’t submit a grant without an institutional sponsor — otherwise a lot would and prices would come down.

We will never see this because the aforementioned post-docs and graduate students are working for wages well below their market value

Not when you include the free tuition.

(hence the trend towards unionization on college campuses for these groups)

No, there are other things behind this, including greed.

This comment is false:

>

The current accredition system precludes this — it would be a very different world if think tanks could offer degrees and receive Federal funds.

In summary, while NSF primarily supports research and development in startups and small businesses, it also engages with larger corporations through various initiatives like funding for research and workforce development.

Not when you include the free tuition

<

This is in reference to my comments about post-docs and graduate students. Note that post-docs do not pay tuition! Furthermore, most graduate students take no classes past their first or most second year, but are typically in graduate school for five to six years. The "free tuition" is simply a transfer from funding agencies to the university with no educational benefit.

Finally, with regard to unionization

An amazing claim. The “greed” in a university setting is among the tenured professors (who teach less than an adjunct and are paid ten-twenty times as much) and administrators. I was speaking to an MIT graduate student a few months ago and they informed me about a third of the graduate students had to work outside of MIT to make ends meet–this at a premier STEM school.

This is the third time we have dealt with this issue in the past 30 years.

First there were the scandals about how some of this overhead money was being spent, the biggest scandal being at Stanford where it was spent on the university president’s wedding, the university yacht, and office floral displays. As I understand it, this resulted in the rate being capped at 26% in 1994 — when the Democrats held all three branches of the legislature, including a 257-177 majority in the House.

The rates apparently then went up and the Obama Administration unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate a unspecified flat rate.

So we have had two Democratic Presidents attempt to reign in this largess. It’s not just Republicans who want to do this.

“To be clear, overhead costs are a legitimate expense for doing research. What is unclear is the correspondence of actual overheads to the monies generated through indirect costs.”

I respectfully disagree — I would argue that research itself is a cost necessary to generate tuition-related revenue, i.e. tuition, state allocation (if public), and alumni donations.

In other words, should research be a self-sustaining enterprise fund that is at financial “arm’s length” of the university itself, or should it be considered a necessary cost to generate tuition revenue — i.e. it wouldn’t be able to have the students if the faculty weren’t also conducting research. Yes, I’m looking at this as a business.

And I am also asking the public policy issues of funding research — what is the purpose of it, and should we have more teaching and less research in our large universities? (I would say YES!)

The current research model was designed in something like 1947 to win the Cold War, which we did in 1990. And now we have this massive Federal funding from a government which is essentially broke.