For the past decade or so, I have worked with students to help them prepare essays for applications to America’s top colleges and universities. Many of my students have historically matriculated to Ivy League and other top-tier universities, and every year, we continue to send a handful of Invictus Prep students to America’s most coveted colleges. Yet, over the past several years, I have noticed an alarming trend amongst my seventeen-year-olds: no one knows how to write anymore.

Don’t get me wrong. There are always exceptions. Every year, several students will shine as the rest prove to be average. That is expected among any sample size of students—a normal distribution of IQ or however you would like to measure intelligence. But what is alarming is not that we are not producing twenty-first century Shakespeares en masse—for that is never the case in any society. What is alarming is that what constitutes “average” writing quality is starkly declining.

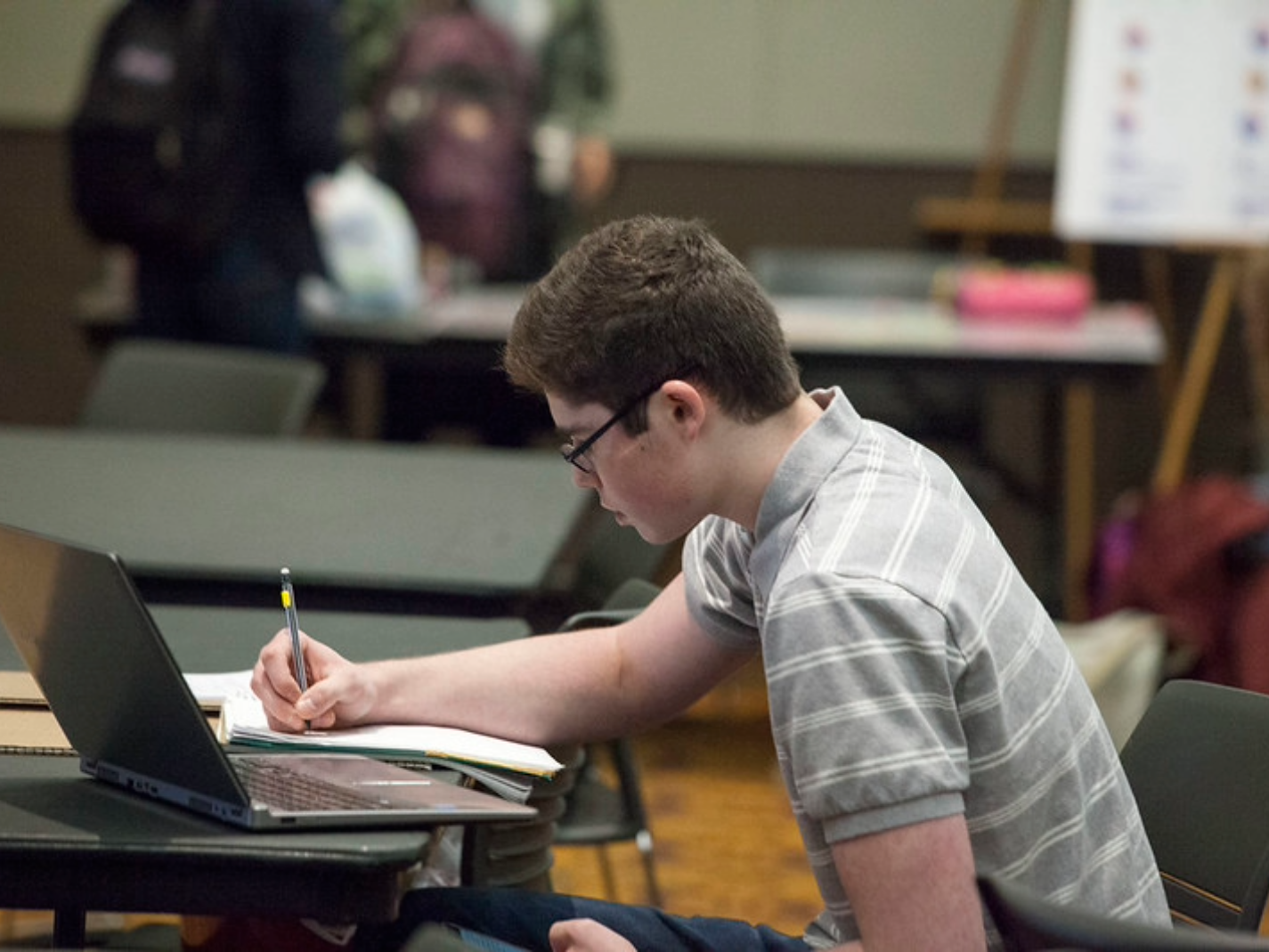

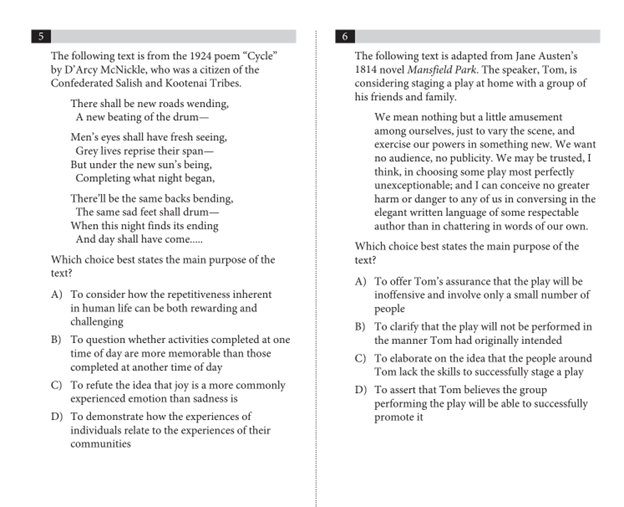

Years ago, many of my students could walk into an SAT testing center and produce a hand-written two-page essay in less than an hour. This sort of skill was not the exception but the norm. Indeed, back when I applied to college in 2015, the SAT required an essay portion that proved to colleges that you were at least capable of stringing basic thoughts together. Not anymore. In 2021, in the wake of the pandemic, the College Board dropped the essay from the SAT before overhauling the exam entirely in 2024. The new version of the SAT is a chilling reminder of the continual erosion of Gen Z’s reading and writing skills. Compare a “literature” reading task from the previous 2016 SAT with the new 2024 digital version:

2016 sample

2024 sample

[RELATED: Lowering the Bar Isn’t Equity—All Students Deserve High Standards]

In the 2016 SAT, students are asked to read and digest a longer chunk of text—often from great literary works—and answer questions that require them to deeply comprehend the subject in question. The new 2024 SAT, however, catering to the abysmal Gen Z attention span, asks students to sit with less than a paragraph of text, shows them exactly where to find the answer to the question, and then prompts them to move on without giving each passage a second thought. And while literature still occasionally appears on the new digital test—though not as consistently as on the previous exam—test takers are primarily fed easier passages from our contemporary world, removing the necessity for students to learn how to understand older literature.

College readiness no longer entails the ability to think critically or to write well.

I have written extensively about the importance of reading great literature to become a great writer. Most of my students, of course, are not training to create the next Great American Novel. Most of my students will continue on to secure professions in tech, medicine, law, or business. But every one of these students will benefit from good communication skills—and every one of these students is currently being failed by an education system that deemphasizes reading and writing. The difficulty of the math questions on the SAT, after all, has stayed consistent across tests.

Why, then, dumb down the reading section? The answer, of course, reflects the priorities of our society: College readiness no longer entails the ability to think critically or to write well.

The problem of student writing quality extends, of course, beyond the sorts of questions that appear on the SAT. AI tools have virtually eliminated the necessity for students to learn anything about grammar, sentence structure, and the eloquent expression of ideas. Every single one of my students has Grammarly preloaded on their browsers, a tool that cleans up spelling and grammar from tasks as menial as writing emails to those as monumental as drafting the college essay. Students use ChatGPT to obtain summaries of longer texts for English classes and tools such as Studocu to generate AI notes on any topic imaginable. Years ago, I could ask a student to write a paragraph in front of me during a meeting, and within moments, we would have a group of sentences in front of us. Now, every student asks for time to “think about it for homework”—most likely because they do not want me to know they will not be the ones doing the thinking. As a result, many students will graduate high school without the slightest knowledge of how to write a sentence without AI tools. And these are not students who will go on to blue collar professions or who did not have access to educational resources—which is a separate problem of its own. The students in question here are students who have access to everything they need—students who come from affluent backgrounds and will graduate from four-year universities. These students have not been failed by a school system that cannot provide them with adequate resources due to a lack of funding. These students have been failed by a society that has simply devalued the importance of the written word.

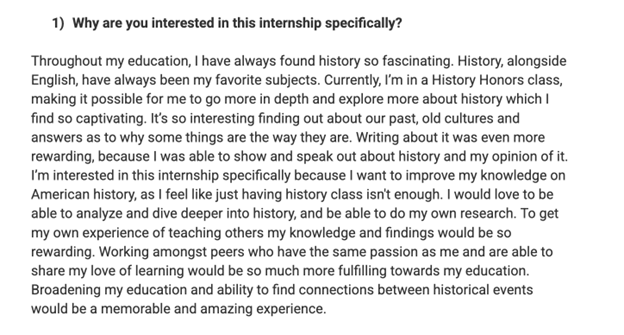

The result is that many of my students can no longer produce coherent writing. Take this example from a sixteen-year-old student applying to summer internship programs:

This writing sample is not from a student who plans to study STEM or learned English as a foreign language. As this student tells us, her favorite subjects are history and English. This student has gone through almost three years of high school and has developed a predilection for the humanities—but can barely write a coherent thought. And even putting abysmal sentence structure aside, we learn virtually nothing from this essay about who she is or why she is interested in the internship—most of her sentences contain nothing but meaningless fluff. But this is not her fault at all—it is the fault of a school system that no longer emphasizes strong critical thinking skills, for it is likely that no one has ever sat her down and taught her what a sentence is really meant to do—that is, communicate an insightful thought. Yet, without exposure to great sentences, how can we expect students to generate their own?

[RELATED: Colleges and the Dumbing Down of America]

As my juniors scramble to prepare their essay materials for this coming college application cycle, I worry that few, if any, students will be able to produce writing worth reading. And as I attempt to stuff seventeen years’ worth of writing pedagogy into several meetings with the kids, I cannot help but wonder why we have decided that students no longer need to be able to write to succeed in this world. Good writing, after all, is the primary proxy for strong critical thinking skills—without it, we will have raised a generation that does not know how to think for themselves.

So, let’s not ignore what our society has done to diminish the importance of good writing. Yes, the damage has been done, but the cause is not totally unsalvageable. Parents, read your kids a book. Force them to diagram a sentence. Do not claim that they can go into a STEM profession without knowing how to write. The more we show students how important it is to write well, the faster we can return to a world where a student can sit through an entire Charlotte Brontë novel and, yes, write an essay about it without the help of ChatGPT.

Follow Liza Libes on X

Image: “College of DuPage Celebrates Student Writing at ‘See Writing Differently’ 2017 10” by COD Newsroom on Flickr

I’m amazed that the author has a halcyon view of 2015 because I was saying the same thing back in the ’90s, long before AI arrived on the scene.

I believe that it all started back in the 1980s with the rather asinine concept of telling students to “write like you speak.” Forty years later, almost all of the K-12 teachers were taught to write that way, and that’s all they know. When I explain the basic five paragraph essay to graduate students, they look at me as if I am some sort of genius.

But it goes further than this — young people today know what they are supposed to think, they passionately believe these things, but they have no idea why they do.

For example, a young lady (an honors student in her 2nd or 3rd year in college) once told me that she was adamantly opposed to private ownership of firearms. When I asked her why, she initially thought that I had misheard her and restated that she was opposed to guns. When I then asked her why she felt that way, it was like a deer lost in the headlights — a minute later she finally concluded that “guns are yucky.”

“Guns are yucky.”

I’m a gun rights advocate and can easily name a dozen reasons why guns should be banned. I’d immediately counter them, but I do know the arguments on the other side of the issue. These kids don’t even know the issues on *their* side of the issue. They are like my Puritan forebears for whom there was the right answer — and Olde Deluder Satan.

And I believe the third thing is the concept that merely passionately believing in something makes it true. One sees a lot of this in the advocacy for electric cars by people who don’t want the power lines to supply this electricity, let alone the power plants to produce it. Facts like volts times amps equals watts or transmission losses over distance don’t matter when one REALLY, REALLY, BELIEVES that the wires designed to power a 100 watt streetlight can also provide 7,500 watts (for a Level II Charger) to recharge an electric car without something really bad happening…

It’s quite clear that our asinine COVID lockdowns has done enduring damage to Gen Z, but that’s not the only reason why they can’t write. And I probably should also mention the two other asinine ideas from the ’80s — Whole Language and Heterogeneous Grouping. Whole Language is way to complicated to discuss here (and not inherently bad if Phonics is included) but Heterogeneous Grouping (aka Mixed Ability Level Grouping) consists of putting children of differing abilities in the same classroom and then having to teach to the bottom lest the classroom be disrupted.

So not only do we not teach things like Phonics and sentence diagramming anymore, we also don’t have college prep courses anymore. This is how you can have a kid who would later go on to graduate first in his class from Harvard sitting next to a Mainstreamed Special Education student — one kid who can argue either side of Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeas corpus in Maryland during the Civil War, and another who keeps proclaiming that his aunt lives in the (Town of) Lincoln.

It’s been a few years since I’ve been in a high school, but I doubt things are much better now and I don’t think it is only AI that is responsible for this.