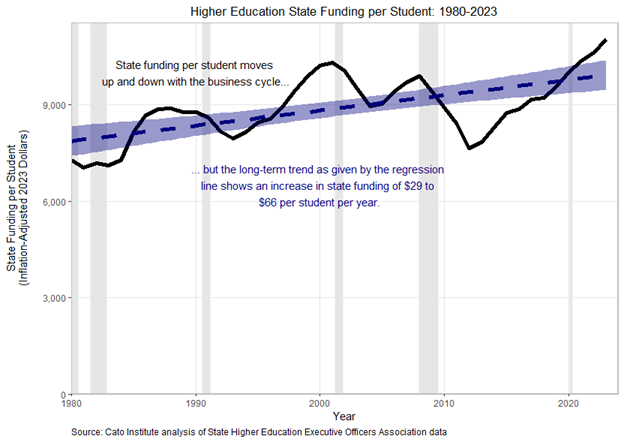

For decades, there have been complaints that states have been cutting funding for colleges, often referred to as state disinvestment. But in my annual report tracking trends in state funding, I show that state disinvestment is a myth. The figure below shows state funding per student over the past 43 years. The dashed blue regression line shows the long-term trend. If state disinvestment was real, the line would be downward sloping, but it has an upward slope, documenting that states have been increasing funding over time by about $48 per student per year.

[RELATED: Shadows of Influence]

Why does the myth of state disinvestment persist?

First, correctly adjusting for inflation is critical when identifying any long-term changes. The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) fails to do so, relying on an ad hoc price index, and is often cited by those arguing that state disinvestment is real. But as my report documents, SHEEO substantially overestimates past funding and is “heavily biased toward finding state disinvestment even in cases when state funding has increased substantially.”

A second reason the myth of state disinvestment persists is that there really are times when states cut funding. As the figure above shows, states tend to cut funding during and after recessions, sometimes dramatically. But these real cuts no more prove states are disinvesting than the subsequent recoveries prove they aren’t. To find the underlying long-term trend, you should avoid year-to-year comparisons, which are subject to cherry-picking and unrepresentative endpoints, and instead rely on regression analysis, which is immune to cherry-picking and accounts for possibly non-representative beginning and ending dates.

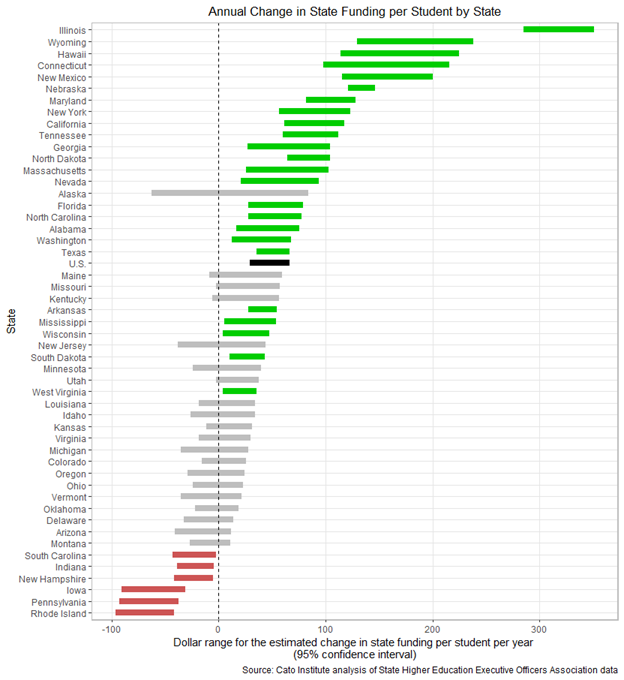

A third reason the myth of state disinvestment persists is that some states buck the national trend. The figure below shows the long-term trend in state funding by state. In particular, it shows the 95 percent confidence interval for the regression estimate of the annual change in state funding per student. There is statistically convincing evidence that 24 states—shaded green—have been increasing funding over time. There is convincing evidence that six states—shaded red—have been cutting funding. Twenty states—shaded grey—have no convincing upward or downward trend in state funding. For those six states, state disinvestment is real. But for every state where state disinvestment is real, there are 4 that have seen increased funding, and more than three that have seen no change in funding.

This debate matters because the myth of state disinvestment has distorted attention away from the real causes of rising college costs.

For example, if state disinvestment was real, it offers a convincing explanation for why tuition has increased so much over the years. After all, if it costs $20,000 per year for a college to educate a student, then if the state cuts funding, the college may need to raise tuition to cover their costs.

But there are two problems with this argument. One, states have been increasing funding over time, not cutting funding, so this argument implies that colleges should have been cutting tuition not raising tuition.

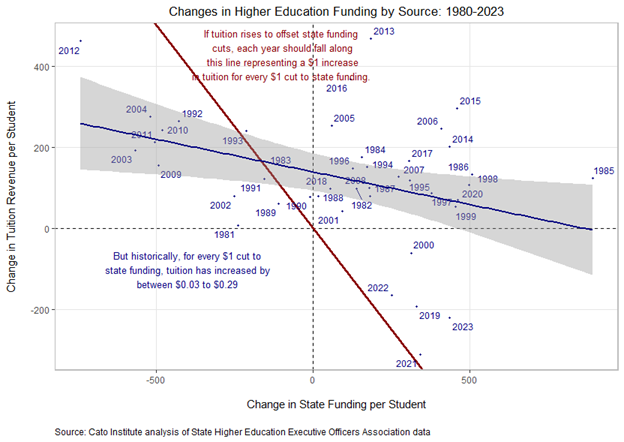

Second, it assumes a 1 to 1 relationship, with tuition rising by $1 for every $1 cut in state funding. The data reject that assumption. The figure below shows the change in state funding and the change in tuition revenue by year. Under the “state disinvestment causes higher tuition” argument, each year should fall along the red line, indicating $1 higher tuition for every $1 cut in state funding. But only a few years fall along the red line. The actual relationship is given by the blue line, which shows that a $1 cut in state funding doesn’t lead to a $1 increase in tuition but rather an increase of $0.03 to $0.29. In other words, the relationship between changes in state funding and changes in tuition is much weaker than advocates assume. Changes in state funding simply do not explain much of the change in tuition.

[RELATED: Cut Government Funding of Scientific Research]

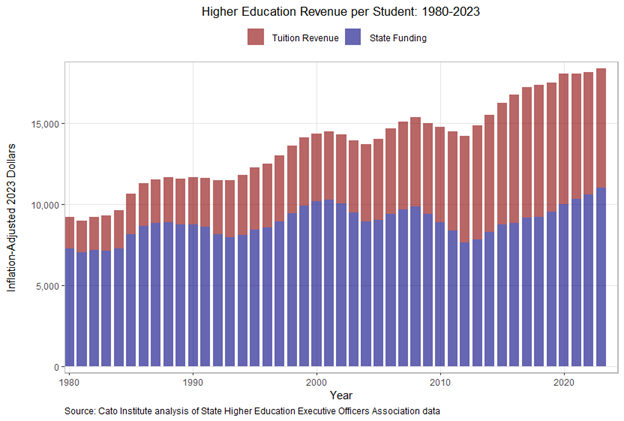

This hints at another problem with the persistent of the myth of state disinvestment—it diverts attention away from real solutions to high college costs. If state disinvestment is real, then the solution for high costs to students is simple—increase state funding. But that only works if total spending by colleges is assumed to be fixed. If colleges are increasing spending, then higher state funding may feed the beast rather than lead to lower tuition. In fact, that’s exactly what’s been happening. The figure below shows the combined state funding and tuition revenue per student over time.

Colleges did raise tuition when state cut funding. But they also raised tuition when states increased funding. Thus, the real cause of college affordability problems is not state disinvestment, which is a myth as states have been increasing funding, but rather out of control growth in spending by colleges.

Follow Andrew Gillen on X.

Image designed by Jared Gould using assets by zimmytws (Adobe Stock Asset ID# 284364895) and gustavofrazao (Adobe Stock Asset ID# 107247391).

There is also the point that John Silbur (of BU) used to make — a public university can borrow money cheaper because it has the full faith & credit of the state behind it — bondholders can recover from the state if the state college defaults. Not so if the private college goes bankrupt.

It’s actually worse than this because of employee benefits and pensions.

Using Massachusetts as an example, all public employees participate in the Group Insurance Commission where they pay something like 20% of the cost of whatever health plan they chose and the Commonwealth (i.e. state) pays the rest. There are other benefits such as life insurance and the cost to the Commonwealth (not university or college) is about 1/3 of the person’s salary.

There’s also a state pension that is based on the average of an employees three highest paid years, and can be up to 80% of that — it’s based on years of employment, age, and if a spouse is included. If the spouse is included and outlives the retiree, payments are made until the spouse dies.

Again, it’s the Commonwealth (general state budget) that funds this pension system (beyond the 7% employees contribute) and not the state university or college system.

Now 80% of university or college budgets are personnel and neither the benefit costs nor the pension costs are being considered in calculating the state appropriation to higher education, even though the state *is* appropriating this money to higher education.