Introduction

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was initially written to ensure that government-funded institutions, such as museums and universities, give human remains and some types of artifacts from past peoples to related modern tribes. Relatedness was to be determined through a preponderance of evidence, using data from archaeology, anthropology, history, biology (e.g., DNA and craniometrics), geography, linguistics, kinship, and oral traditions.

The artifacts to be returned fell under one of three categories: funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.

In 1990, when NAGPRA was passed, “funerary objects” were defined as follows: “objects that are reasonably believed to have been placed with individual human remains either at the time of death or later” and “items exclusively made for burial purposes or to contain human remains shall be considered as associated funerary objects.”

“Sacred objects” were defined as “specific ceremonial objects which are needed by traditional Native American religious leaders for the practice of traditional Native American religions by their present day adherents.”

And, “objects of cultural patrimony” are those that have “ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to the Native American group or culture itself, rather than property owned by an individual Native American.”

Artifacts that did not fall into these categories were not to be repatriated; museums and universities were to retain naturally occurring materials or waste found at sites for continued research. Unfortunately, repatriation decisions have greatly deviated from NAGPRA’s original intent—from waste to fine arts, repatriation ideology is emptying our museums and universities. Here are some examples.

Coprolites and other waste

Coprolites are fossilized feces. Anthropologists can use this petrified human waste to reconstruct diet, look for evidence of parasitic diseases, and extract DNA for biological relatedness studies. A 2020 review article by Shillito and colleagues highlighted the many studies completed on coprolites, including research that found pre-contact Pueblo agriculturalists from Utah consumed a fungus known to counteract the nutritional deficiencies associated with a maize diet. Thus, this stinky material can be used to reconstruct the past.

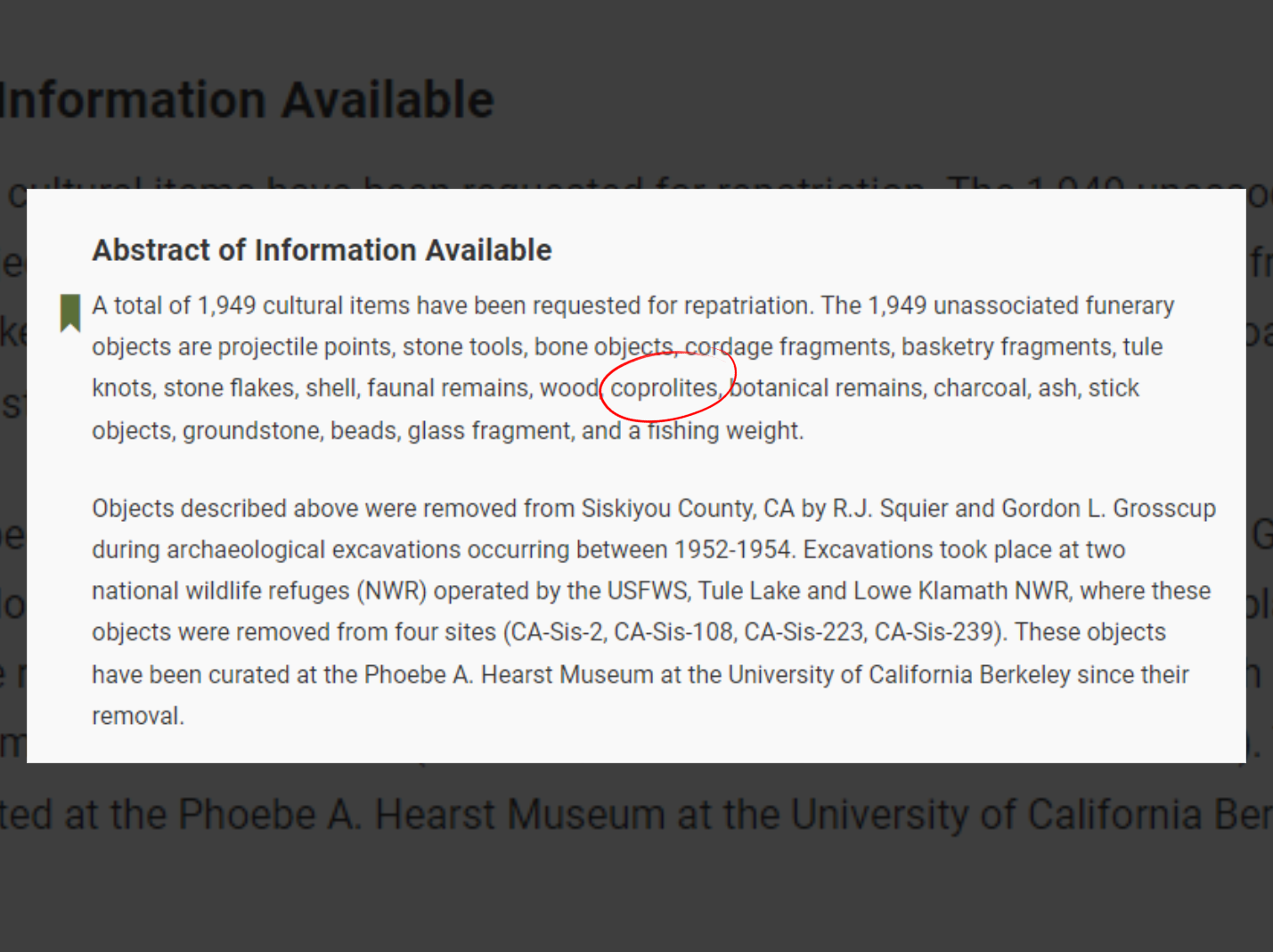

Yet, now, Native American repatriation activists want their s**t back. For example, Klamath tribes and the Modoc Nation of Oregan have requested the repatriation of coprolites from the U.S. Department of Interior Fish and Wildlife Services—the request has been approved. The tribes insist that the coprolites are unassociated funerary objects: does that mean that they buried their loved ones in feces?

It’s not just coprolites; animal bones left over from meals are being repatriated, too. From Sonoma State University, “dietary bone remains” have been requested for repatriation by various Me-Wuk tribes who list these items as “objects of cultural patrimony”—I didn’t know that the remains from yesterday’s meals were of “ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance” to tribes today. If some modern-day Native American eats a KFC chicken dinner on Monday, are the bones going to become objects of cultural patrimony by Tuesday? By next week, will they be sacred?

Faunal remains such as these can be used to reconstruct diet or teach osteology, especially for forensic anthropologists, who need to learn to identify the difference between nonhuman and human remains. In a recent article about new repatriation regulatory changes, it was reported that an osteology instructor in California was denied access to animal bones from a 19th-century hospital dump because the tribes hadn’t been consulted yet!

Many more tribes are requesting animal bones and even vegetable matter.

The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community identified “non-human mammal, bird, and fish bones” as “unassociated funerary objects” (i.e., objects not found with human remains, but presumed to be related a burial that hasn’t preserved) and requested to repatriate them from Western Washington University. And, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology is repatriating “charred corn cobs” to the Onondaga Nation. What next? Banana peels? Orange seeds? Come on man!

Artifact Replicas

The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology has approved a repatriation request from Sitka Tribe of Alaska of five headpieces, two helmets and three hats, that were purchased between 1918 and 1925 by Louis Shotridge, a curator of Tlingit descent. The items were created for display by Augustus Bean (1850-1926), a Tlingit tribal member. Bean was paid generously for these replicas; one of the hats—the Ganook hat—was purchased for $450.00 in 1925. But the Sitka Tribe of Alaska will be taking these hats away from public viewing based on a retro-sacredness that is anathema to the original intention of NAGPRA. Interestingly, these items were nearly repatriated in 2011, but competing tribal claims for the objects had stalled the repatriation!

I wonder how long it will be before the Tlingit demand the repatriation of a medicine hat replica made by the Smithsonian in collaboration with the tribal clan leader Ray Wilson from Sitka, Alaska. In 2019, the Smithsonian and the tribal collaborators conducted a ceremony in Alaska to “put spirit into the new hat—making it a living sacred object (at.όow), just like the original”—this now seems like a recipe for disaster. Let’s hope the spirits don’t get too restless!

Contemporary Art

As mentioned above, NAGPRA’s intention was to exclude artwork. Thus, until recently, most art museums had little engagement with repatriation efforts, specifically NAGPRA. Yet, with the “Final Rule” changes in NAGPRA, artwork is being repatriated at an unprecedented rate. Artwork repatriations were not unheard of, but they were mainly replicas of artifacts. Now, even contemporary artworks that are not replicas of artifacts are being targeted.

Harry Fonseca, a Native American artist who lived from 1946 to 2006, was trained at Sacramento City College and Sacramento State University. As a Nisenan Indian, he was enrolled in the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians. His most famous works are those of coyote-themed paintings that included coyotes in leather jackets, coyotes playing pianos, coyotes dancing in flamenco attire, and so forth. Fonseca’s works have been displayed and sold all over the world. Yet, the Folsom History Museum has approved a repatriation request from the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, who claim that Fonseca’s artworks are items of cultural patrimony.

Artworks and replicas of artifacts made for display were not intended to be repatriated through NAGPRA. In 2018, historian Ron McCoy wrote about the collapse of these distinctions, especially when it comes to defining replica artifacts made for display as “sacred.”

In a 1990 senate report, the Select Committee on Indian Affairs discussed concerns about the definition of “sacred.” They noted that there were concerns expressed that “any object could be imbued with sacredness in the eyes of a Native American, from an ancient pottery shard to an arrowhead.” But the Committee tried to reassure the Senate by stating that they intended “that a sacred object must not only have been used in a Native American religious ceremony but that the object must also have religious significance.” Further, the Committee wrote that it “does not intend the definition of sacred object to include objects which were created for purely a secular purpose, including the sale or trade in Indian art.”

Non-Native Materials from Native Grounds

For History Reclaimed, I wrote about the repatriation and ‘decolonization’ efforts of the University of California at Berkeley’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Curators were repatriating a 16th century Spanish breastplate and Ming dynasty vases to the Graton Rancheria tribe. The repatriation of non-Native Materials, especially artifacts of historical importance, is likely to negatively affect our ability to teach history to the public. Learning about history is an essential part of our ability to appreciate modern times, prevent us from repeating past mistakes, and take pride in our nation’s accomplishments. Yet, current repatriation notices are full of materials to be given to tribes that they could not have made themselves, like glass, nickel silver brooches, and brass and bronze ornaments.

And, in a bizarre tale, a Centaur display—a Centaur is a mythical beast from ancient Greek Legend: part-man, part-horse—created by recently deceased artist and University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh retired biology professor Bill Willers in 1980 is likely to be repatriated to Wisconsin tribes. The Centaur, created from Shetland pony bones made available by the University of Wisconsin, Madison veterinarian school, and medical supply human remains from the university that came from India, was purchased by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, to display and educate people about hoaxes. According to the University of Tennessee, Knoxville provost: “The NAGPRA process, alone, will determine whether a Native American Tribe has a valid claim and whether the Centaur, in whole or part, will be repatriated to them.” And, a University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh vice chancellor has stated that even the display case, which was made at the University of Tennessee, and the fake Greek artifacts will also be returned because these items now have “spiritual connections” with the human remains.

Conclusions

NAGPRA’s original intentions have been hijacked and repatriation activists are identifying all sorts of objects as sacred, funerary objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.

Anthropologists and archaeologists are enabling the illegal emptying of research and teaching facilities. Even replicas are no longer safe in our universities. Historians and art museum curators, too, are allowing the repatriation activists to strip museum walls of contemporary Native American artwork—making it unlikely that new pieces will be purchased. It’s likely due to a mixture of wokeism, white guilt, and fear of being called a racist and colonialist if you dare to question any indigenous activist’s repatriation requests.

The purpose of these repatriations is to stop research into the past and to hide the fact that they lived in a Stone Age culture, not even making alloyed metals. Modern tribes don’t want scientific evidence that reveals the accurate story of their past—perhaps that they faced illnesses before contact with Europeans or that they overhunted certain animals and, thus, were not the world’s first animal conservators and environmentalists —as the noble savage myth posits.

But another issue is that by counting every animal bone, every unmodified stone, every replica, and every coprolite piece, the number of unreturned “cultural items” is greatly exaggerated. When newspapers report that universities are holding onto thousands of Native American items, the average reader would be shocked to learn that most of this is refuse, soil, animal bones, and stones. For instance, the Sacramento Bee stated that UC Davis has 9,000 items, but this includes 101 ground stone, 124 unworked stone/minerals, 147 pieces of charcoal, 172 unmodified shells, 197 unmodified nonhuman bone, 240 plant/miscellaneous organic materials, and 281 debitage from a single site!

Finally, the requests are also attempts to extract government money for repatriation and reburial ceremonies. Also, perhaps, the intention is to resell items of value, such as the artwork; it is particularly galling when museums have paid for the artworks—even sometimes purchased by Native Americans, from Native Americans, or gifted. There’s a name for the practice of giving gifts and then demanding them back!

Screenshot of Notice of Intended Repatriation: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Klamath Falls, OR on Federal Register

Artifact repatriation parallels public name appropriations: their owners should have the human right to reclaim or permit them.

Pretty simple really.

And who is taking awa someone’s property?

Stanton Green, PhD

Professor Emeritus Anthropology

Except. . . We have a federal law (1966) that requires looking for archaeological sites and judging if they are of educational interest or historic importance. And if so, taxpayer funds are provided to excavate the cultural material, analyze it, and write reports describing the findings- as required by that federal law. And the artifact collection, including all notes, photos, drawings, and maps are to be stored in perpetuity in a temperature and humidity controlled secure structure. That 1966 law says this collection is important information and has research value for the American public- now and in the future.

I completely understand returning human remains and burial goods to tribes. That is not the problem. The problem is now that some tribes are claiming EVERYTHING is sacred. That is not the purpose of NAGPRA.

Since NAGPRA (basically in 2000), most Tribes have been pushing the rule – asking then advising and now telling archaeologisys not to photograph certain items. The response- OK we will draw them. The reply-Nope. No drawings. And museums or researchers can’t even make 3d reproductions of anything now in their collection. And don’t allow even those who excavated the site access to the artifacts or their own notes once they have been included in the collection that is securely stored. Some Tribes have decided the archaeological report will not be punished as an article or site report – not reported at all. Usually only other archaeologists and some in the public would be interested in these reports.

So my question- WHY even have Section 106 if none of the information about the site has been or will be peer-reviewed or accessible for others to research and the artifacts themselves are inaccessible (for new investigative technology), or knows what was found that may be important? Why dig at all? Just let the bulldozers obliterate it all and we will remain ignorant about our own nation’s history.

In addition, this federal law used to only apply to artifacts recovered because of Section 106. Suddenly, it applies to any facility that has ever received federal money through a grant or loan no matter how much. If a small museum received a grant of even $500 40yrs ago to make their facility compliant with ADA – that places them under the provisions of NAGPRA. So now, State Archives and small museums with their own small collections that were donated by the pubic – artifacts collected from private land that were picked up by a farmer and given to some facility so that fellow citizens could see them, are subject to the new NAGPRA guidelines. I’m pretty sure that scenario was never considered even +25 yrs ago as NAGPRA was being written.

Shouldn’t the 16th Century Spanish breastplate be repatriated TO THE SPANISH?!?

Arguably it is military property and hence comes under the same International Law as military shipwrecks, which remain the property of the nation whose ship it was.

And as to the feces, there is another International Law that comes to mind, that of “salvage” — essentially that one who recovers or helps recover another’s property is entitled to a reward that at least covers the cost expended and a reasonable profit.

So you can have your feces back, after you pay us for finding it and preserving it, at $5 per piece per day, for the past 70 years….

And there are laws about abandonment of property that come to mind as well. A favorite police tactic is to retrieve the trash left out for collection by a suspect and to go through it hoping to find something that will give them probable cause for a warrant. SCOTUS has upheld this saying that the trash was “abandoned.” Same thing with DNA on cigarette butts.

Likewise cities routinely monitor sewerage for evidence of COVID — do the Indians want their sewerage back as well?

I’m reminded of Reconstruction when there was an effort to correct legitimate past injustices (i.e. slavery) that went way overboard and eventually led to Jim Crow. I would caution the Indian tribes to be careful lest history repeat itself in ways that they very much would not like.

Sadly, I’m not surprised that the cowards currently running academia are willing to sell out to these bullies — but one needs to remember that half the country already has open contempt for higher education and money speaks. The Native American monopoly on gambling is not going to last forever. All but five states now have a state lottery, states are opening casinos and the market is becoming saturated — tribal casinos already aren’t the money-makers they were 30 years.

Throw that in with the inevitable populist takeover of the Federal Government — maybe this fall, maybe ten years from now — and these spineless cowards will very quickly start dancing to a very different tune an a desperate attempt to save their institutions and many won’t be able to. Add in how things start getting interesting in the Fall of 2026 when the babies not born in 2008 aren’t showing up as freshmen and a lot of colleges are going to fail.

And to the Indians I ask one final question: If Congress will allow you to take other people’s things away from them right now, what might a future Congress allow them to take away from you? You have already destroyed the principle of property rights so you’ll have no recourse then…

One other thing:

“…Rule 19 is the “Required Joinder of Parties” and so when the judge decides that the tribes are required Joinders, but they cannot be joined (because of the 11th Amend. — i.e., sovereignty), then this leads to the catch-22!”

A sovereign can waive its immunity and states often do because they want to participate in the trial. I am not an attorney but I don’t see how the tribe can be *in* court without having waived their right to immunity from that court.

Once they have voluntarily surrender their immunity by choosing to be a party to the suit, they then are subject to joinder like any other party because they have waived their immunity. You aren’t specifying if this is State or Federal Court, but this is like being half pregnant — one either is subject to the court or one is NOT subject to it.

How can they sue to get their stuff back without being subject to the court — otherwise it couldn’t help them on jurisdictional grounds. Something is really wrong here.