As a country, in celebrating resistance, we have lost sight of the important difference between resistance and resolution.

For example, even before Donald J. Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2017, plans were afoot to thwart his agenda. Those plans coalesced under the hashtag #Resistance, and included marches, demonstrations, plots for electors to ignore state election results, a myriad of lawsuits, the interminable and discredited “Russia hoax,” calls to invoke the 25th Amendment, and even boasts from high officials that they were undermining the president’s efforts from within. The Resistance continued through Trump’s two impeachments, the lawfare waged against him since he left office, and now the not-so-secret plans to challenge election results and a second Trump administration should he be reelected.

Depending on your bent, “Resistance” may evoke Luke Skywalker’s fight against the Empire or La Résistance française against the Nazis. Perhaps most powerfully for Americans, it recalls our early patriots’ daring stance against British tyranny.

But is the analogy to the colonial patriots accurate?

A good point of comparison took place on September 9, 1774, and provides yet another installment in NAS’s series on the events leading up to the American Revolution 250 years ago.

The summer of 1774 was a time of crisis in colonial Massachusetts. In response to the Boston Tea Party and other acts of—ahem—resistance to British constraints, Parliament imposed the “Intolerable Acts,” embargoing the port of Boston, quartering soldiers in the city, and suspending representative government in the colony. Local British officials also began confiscating Americans’ arms and the powder required to use those arms.

Meanwhile, citizens in Massachusetts cities and towns were meeting to discuss what to do. These meetings resulted in the appointment of delegates to county-wide gatherings and to the first Continental Congress, which began its deliberations in Philadelphia on September 5.

Within the Commonwealth, each county produced a “resolution” as a result of these gatherings. The most famous by far was that produced by Suffolk County, which included Boston and all the municipalities that today form both Suffolk and Norfolk Counties. The “Suffolk Resolves” were approved on September 9 in the Town of Milton, Massachusetts—about a block from my home.

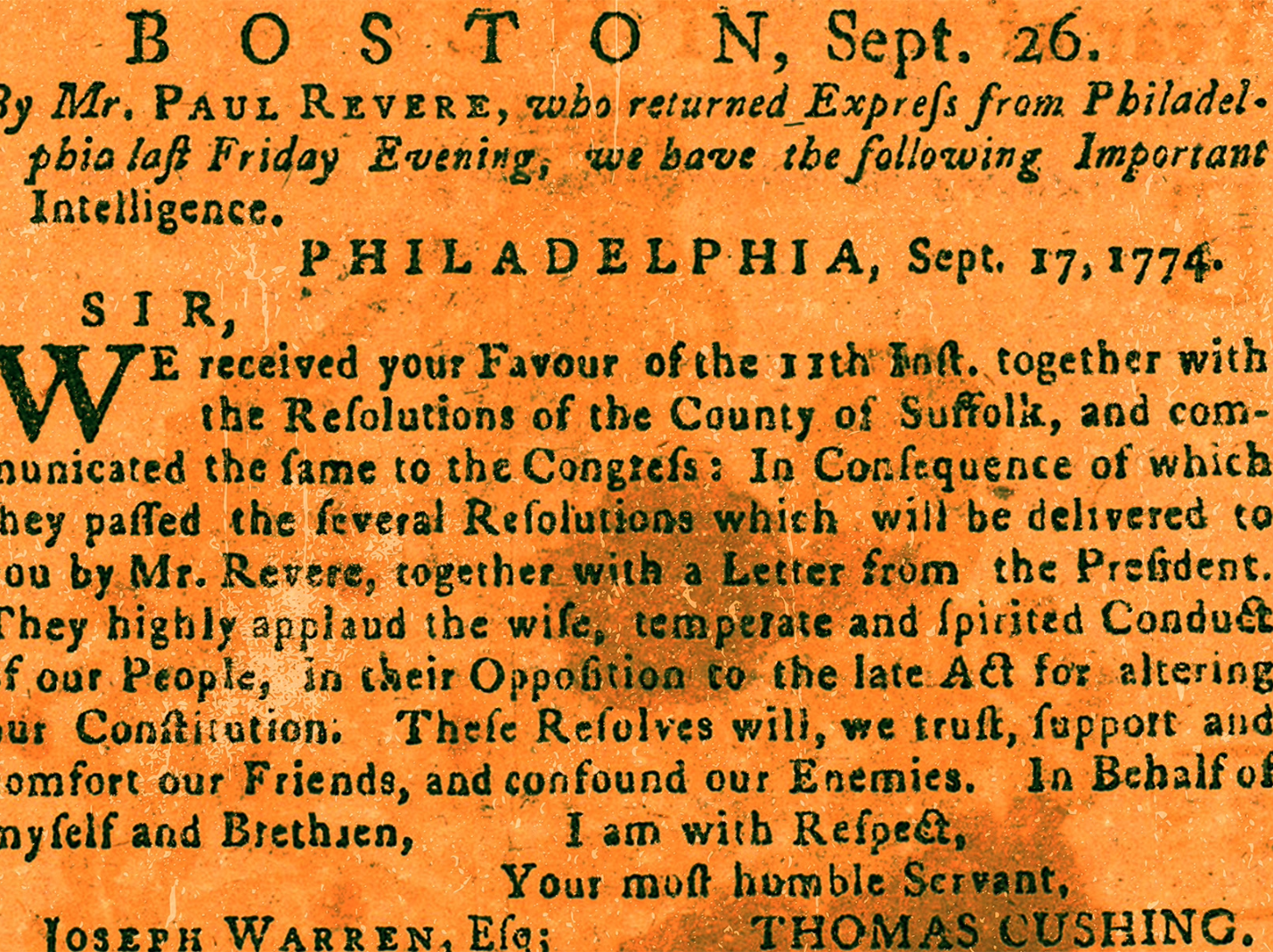

The Suffolk Resolves were important for their content and effect, which I’ll turn to in a moment. Upon their approval, their lead author, Dr. Joseph Warren, directed his friend Paul Revere to carry them in haste to Philadelphia. Revere delivered the Suffolk Resolves to the new Continental Congress on September 16—the first paper that the new Congress reviewed. On September 17, Congress had the Resolves read aloud, voted to approve each paragraph, and then—despite the close secrecy of the rest of the Congress’s deliberations—voted to publish the Suffolk Resolves in newspapers around the colonies. All these votes were unanimous, which was quite a feat for a body that included delegations as different as those from Massachusetts and South Carolina.

The publication of the Suffolk Resolves even reached England, where former Prime Minister Lord Chatham—speaking to the House of Lords about the resolutions published by the Continental Congress—said, “I trust it is obvious to your lordships that all attempts to impose servitude upon such men, to establish despotism over such a might continental nation, must be vain, must be fatal.” The Congressional Journal and private correspondence of its members also reveal that the Suffolk Resolves decidedly influenced the Congress’ July 6, 1775 “Declaration Upon Taking Arms” and, above all, the Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776.

So, what did the Suffolk County delegates resolve that caused such a stir?

The Resolves consist of a two-paragraph introduction, which describes the location and process of the meeting, followed by a preamble, and then 19 paragraphs that the delegates “have resolved and do resolve.”

The resolutions proceed in a logical fashion:

- The first affirms the delegates’ allegiance to King George as the rightful ruler of the British realm and colonies in America, while the second also affirms the delegates’ duty to defend their “civil and religious rights and liberties.”

- The third and fourth describe and reject the Intolerable Acts, while the fifth through eighth resolutions demand that colonists take no part in the county courts, tax collection, or crown offices, so long as the Intolerable Acts remain in force.

- The ninth and tenth express alarm at the British fortification of Boston Neck and Parliament’s accommodation to Catholicism in Canada. In response, the eleventh and twelfth recommend that Suffolk County’s towns take control of and exercise their militias—at least once per week— but only for defensive purposes.

- The thirteenth recommends that servants of “the present tyrannical and unconstitutional government” be taken into safe custody until the patriots that the Crown has arrested are released.

- The fourteenth and fifteenth call for withholding all commerce with Great Britain as well as for developing colonial manufactures.

- The sixteenth and seventeenth call for a Provincial (i.e., Massachusetts) Congress and deference to the Continental Congress just convened.

- Recognizing the uneasy state of the Commonwealth, the eighteenth resolution does “heartily recommend” that colonists not “engage in any routs, riots, or licentious attacks upon the properties of any person whatsoever, as being subversive of all order and government, but, by a steady, manly, uniform and persevering opposition, to convince our enemies, that, in a contest so important, in a cause so solemn, our conduct shall be such as to merit the approbation of the wise, and the admiration of the brave and free of every age and of every country.”

- The final resolution enjoins the Committees of Correspondence to inform each other if the British should attack any town.

This summary fails to capture the stirring but serious tone of the Suffolk Resolves, which Lord Chatham described as “words of decency, firmness, and wisdom.” Still, it’s clear that the Resolves were more than a mere boycott of British goods or a refusal to serve in the county courts. Those would be acts of Resistance but not Resolution.

This point is made clear by the preamble to the Resolves, which is worth quoting in full:

Whereas the power but not the justice, the vengeance but not the wisdom, of Great Britain, which of old persecuted, scourged and exiled our fugitive parents from their native shores, now pursues us, their guiltless children, with unrelenting severity; and whereas, this then savage and uncultivated desert was purchased by the toil and treasure, or acquired by the valor and blood, of those our venerable progenitors, who bequeathed to us the dear-bought inheritance, who consigned it to our care and protection, – the most sacred obligations are upon us to transmit the glorious purchase, unfettered. by power, unclogged with shackles, to our innocent and beloved offspring. On the fortitude, on the wisdom, and on the exertions of this important day is suspended the fate of this New World, and of unborn millions. If a boundless extent of continent, swarming with millions, will tamely submit to live, move, and have their being at the arbitrary will of a licentious minister, they basely yield to voluntary slavery; and future generations shall load their memories with incessant execrations. On the other hand, if we arrest the hand which would ransack our pockets ; if we disarm the parricide who points the dagger to our bosoms ; if we nobly defeat that fatal edict which proclaims a power to frame laws for us in all cases whatsoever, thereby entailing the endless and numberless curses of slavery upon us, our heirs and their heirs for ever; if we successfully resist that unparelleled usurpation of unconstitutional power, whereby our capital is robbed of the means of life ; whereby the streets of Boston are thronged with military executioners ; whereby our coasts are lined, and harbors crowded with ships of war ; whereby the charter of the colony, that sacred barrier against the encroachments of tyranny, is mutilated, and in effect annihilated ; whereby a murderous law is framed to shelter villains from the hands of justice ; whereby that unalienable and inestimable inheritance, which we derived from nature, the constitution of Britain, which was covenanted to us in the charter of the province, is totally wrecked, annulled and vacated, – posterity will acknowledge that virtue which preserved them free and happy ; and, while we enjoy the rewards and blessings of the faithful, the torrent of panegyric will roll down our reputations to that latest period, when the streams of time shall be absorbed in the abyss of eternity.

The Suffolk Resolves call for resistance but not for resistance’s sake. They are a resolution to defend an inheritance. This inheritance is of land and of liberty. And this liberty is not license. It is liberty under laws and a constitution, which is itself derived from nature, Great Britain, and a long series of covenants and traditions. The Suffolk County delegates knew what they were for, not just what they were against.

One final note on the Suffolk Resolves: As its authors observe, resistance easily becomes a mob phenomenon, characterized by “routs, riots, or licentious attacks”—the sort of resistance with which the riots of the Summer of 2020 or January 6, 2021, made us only too familiar. Resolution—while it can be shared—finds its foundation in the reasoned will of the individual citizen. Historians sometimes emphasize the role of the cultivated Dr. Joseph Warren in writing the final draft of the Suffolk Resolves. No doubt Warren’s pen gave the Resolves much of their vigor. But, an examination of the minutes of town meetings in the summer of 1774 reveals that ordinary citizens in towns such as Milton had already debated and agreed upon many of the main points in the Resolves.[1]

Elites can and do whip up Resistance—often for their own power or profit. Resolution belongs to a people who are free, because they are reasonable. Are Americans still capable of such deliberation, the only “populism” worthy of the name?

[1] On this point and many others related to the Suffolk Resolves, readers would benefit from the careful research published in 1921 by Lauriston L. Scaife, a member of the Milton Historical Society, and (incidentally) great-uncle to Richard M. Scaife, whose philanthropy has supported NAS.

Art by Beck & Stone