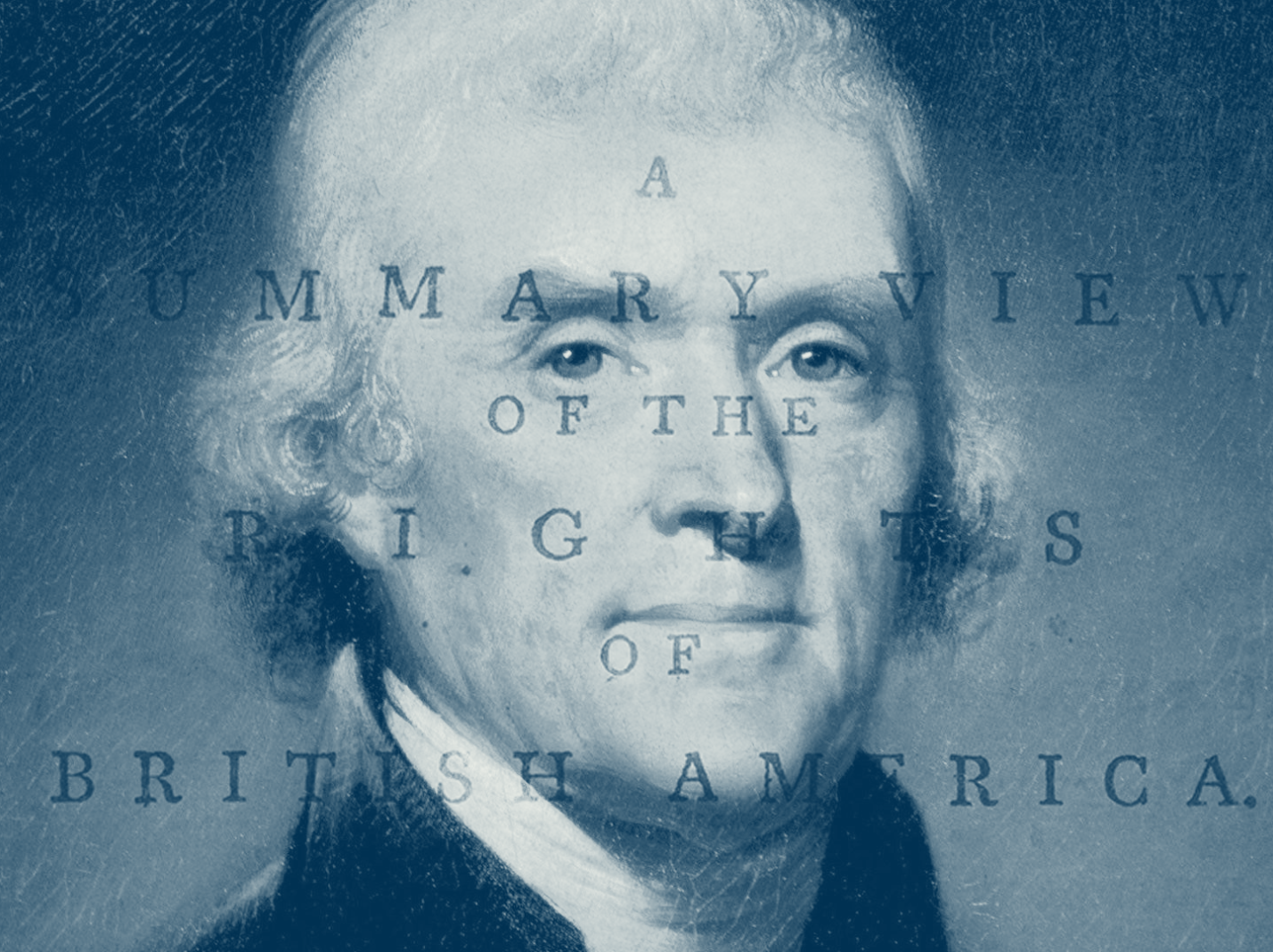

Thomas Jefferson wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America in 1774, basically the first draft of the Declaration of Independence. That’s how he got to the drafting Committee of Five for the Declaration in 1776. Fine job you did in 1774, Thomas; why don’t you write another version now?

Back in 1774, America wasn’t ripe for revolution—quite.

The different colonies were preparing for the First Continental Congress. Virginia was preparing a Virginia Convention—not authorized by law!—which would send delegates to that Congress. And, while it soon became a public pamphlet, the young Thomas Jefferson wrote the Summary View hoping that the Virginia Convention would take its arguments on board as it briefed its delegates to the Continental Congress. Jefferson wrote, not as an individual, but as if he were a committee:

Resolved that it be an instruction to the said deputies when assembled in General Congress with the deputies from the other states of British America to propose to the said Congress that an humble and dutiful address be presented to his majesty.

Jefferson wrote fire-breathing material.

What is the king?

[H]e is no more than the chief officer of the people, appointed by the laws, and circumscribed with definite powers, to assist in working the great machine of government erected for their use, and consequently subject to their superintendence.

Who made America?

America was conquered, and her settlements made and firmly established, at the expence of individuals, and not of the British public. Their own blood was spilt in acquiring lands for their settlement, their own fortunes expended in making that settlement effectual. For themselves they fought, for themselves they conquered, and for themselves alone they have right to hold.

What is the character of the British government today?

Single acts of tyranny may be ascribed to the accidental opinion of a day; but a series of oppressions, begun at a distinguished period, and pursued unalterably through every change of ministers, too plainly prove a deliberate and systematical plan of reducing us to slavery.

What should be done about slavery?

The abolition of domestic slavery is the great object of desire in those colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves we have, it is necessary to exclude all further importations from Africa.

Why do Americans speak so freely?

That these are our grievances which we have thus laid before his majesty with that freedom of language and sentiment which becomes a free people, claiming their rights as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate. Let those flatter, who fear: it is not an American art.

Jefferson only avoided outright treason by indirection: “It is neither our wish, nor our interest, to separate from [Britain].” Unstated, that formulation allows that it is America’s right to separate from Britain, and even to raise the idea of separation—there is a clear suggestion of what must follow if Britain does not rescind its tyrannous policies.

What does it mean for a Virginia aristocrat, a wealthy planter who should be a mainstay of the status quo, to start supporting revolution? It’s as if a Peter Thiel or an Elon Musk or a Bill Ackman or a Donald Trump were to start arguing for liberty. Or, even more closely parallel, as if a venture capitalist from Ohio wrote a memoir as suddenly popular in its day as Jefferson’s Summary View was in its, a little work that provided a first draft for a revolution to come.

The corrupt old regime always has a myriad of inducements to keep the well-heeled in line; when they start to go off the reservation, you know it’s rotten to the core. And some of those aristocrats can be quite eloquent—new Jeffersons writing the first drafts of liberty.

It’s always worth writing the first draft for liberty and independence. It means you’re first in line to write the final one.

Art by Beck & Stone

“a venture capitalist from Ohio wrote a memoir as suddenly popular in its day”

Coming from a culture similar to that, and having actually driven the school bus route described in Carolyn Chute’s _Beans of Egypt, Maine_ (the Line Road in Gorham, ME), the problem I have with said venture capitalist’s memoir is that while it accurately depicts *some* of the families, it does not depict all of them.

But his point about not having a cell phone while those not working do is real.