This marks the second of a two-part series by digital artist Joe Nalven who explores the integration of AI in campus art galleries as an approach to supersede academic silos. Part one of this series can be found here.

Gallery One ─ Identical Objects, Words, Different Perceptions

Students will discuss how words that describe an object can influence the viewer’s perception of the object.

Object

Words Shaping the Perception of an Object

With this one black line on a white canvas, we see three distinct pictures: the number one, a tree on a snowscape, and black paint on a white canvas. Other images can be “seen” with different word descriptors ─ a picture of the universe, a magical line, a discovered archeological artifact. The physical markings are the same, but the context—defined by words—set them apart as different “objects” or, different perceptions of visually similar objects.

The discussion can branch out into the multiple meanings often attached to words. The meaning of a word may be affective, thematic, social, conceptual, and more. Words are arbitrary labels—a “dog” is a hound, perro, chien, собака, 狗. Legends, rituals, and mythos are gap fillers to how (human) language became the foundation for knowledge—In the beginning was the Word (logos) (New Testament); Vāc is the Hindu goddess of speech; while the indigenous people of the Andaman Islands attribute the giving of language to the god Pūluga. Scientific theories of the origins of language are manifold, often queued to when humans developed the capacity for speech.

The teachable moment in the first room of the art gallery might conclude with something along these lines: The human experience is not a closed enterprise. Our imagination is inflected by the world of words. These words are our guideposts that we are taught and learn to use in a particular cultural space. We can bend and shape these words to our particular needs.

Moreover, our perception of the world is influenced by the words and language we use to describe it.

At this point, students would move to the next room.

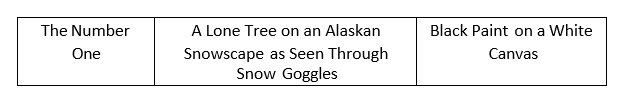

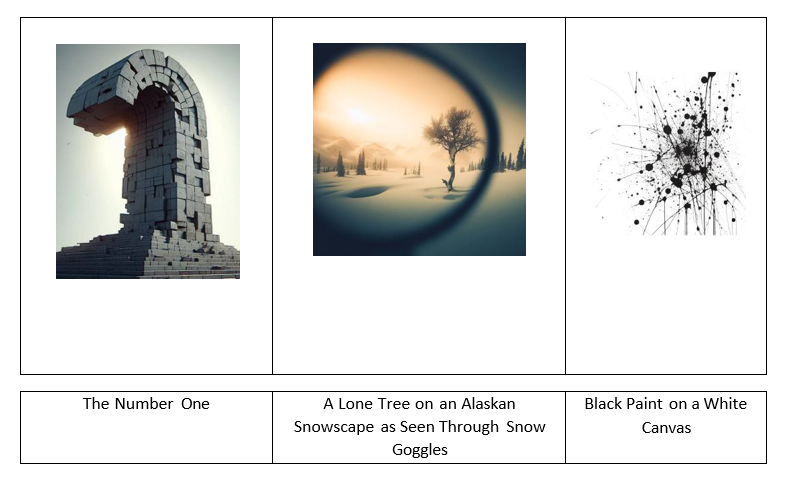

Gallery Two ─ LLM, Generative Prompts (Words), Different (GAI) Objects

What is striking in the second room is that while the text is identical, the images are radically different. The text prompt that is put into the LLM’s generative model presents images other than those in the prior room.

Why is that?

What does this say about the descriptions of the world by humans and the lack of correspondence with GAI representations?

Further questions might include: How much precision can words have as they attempt to map objects in the world? Does the nature of human language’s rootedness in ambiguity and plurisignificance frustrate exact image representation? Would it be more useful to understand those AI-generated images as ones of surprise rather than failures to find isomorphic correspondence? How does human epistemology of the world compare to LLM statements? Our knowledge of the world is framed by culture and founded on biological systems; LLM statements are built on machine language and algorithmic layers and loops.

Despite the discontinuity of human knowledge and LLM statements, LLMs demonstrate an ever-increasing production of problem-solving and curation of existing datasets that is useful to human activity. That is, the lack of full understanding between human and LLM representations does not preclude the functionality of collaborative efforts between the two. The question of human safety relative to the increasing capabilities of LLMs remains elusive.

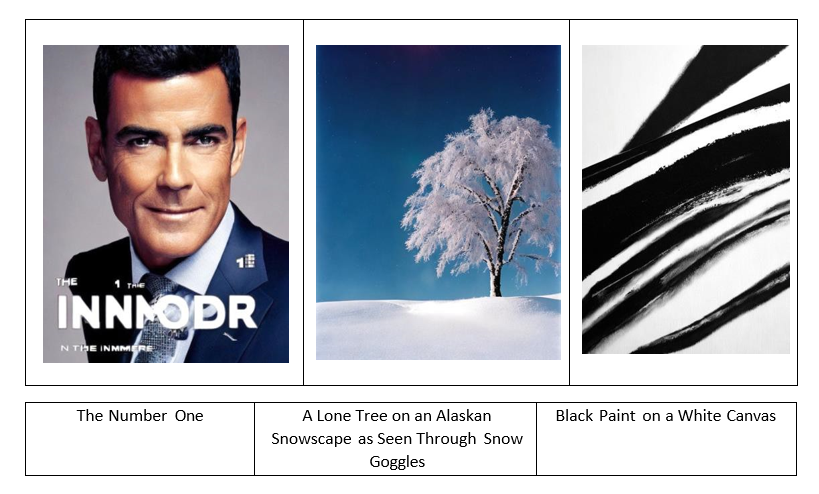

Gallery Three ─ The Continuity of Disciplinary Knowledge, Art History

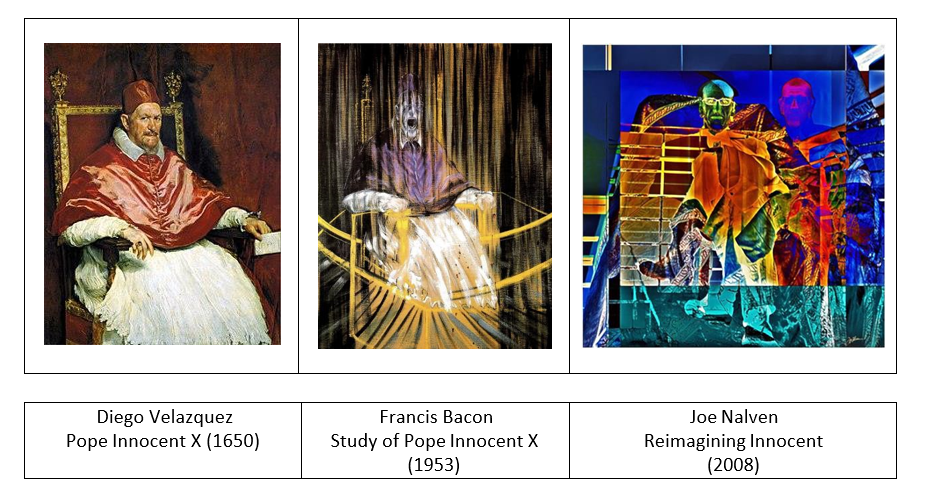

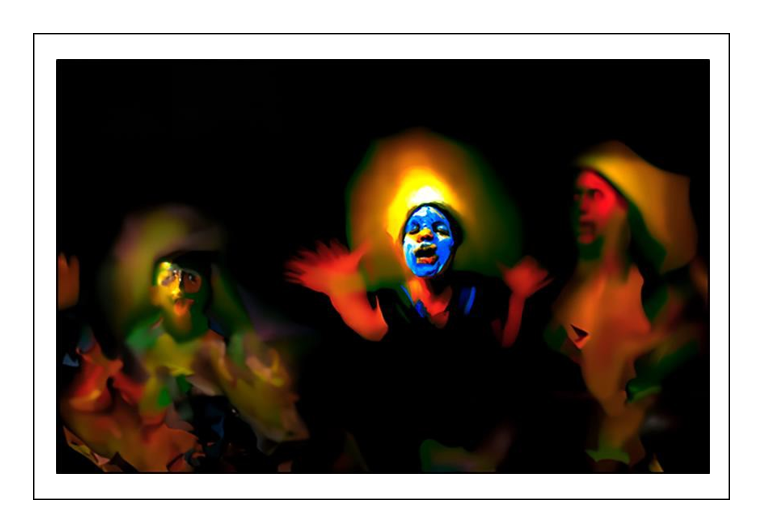

The final room feels familiar. The images draw on artists across several centuries. Their images represent authority figures. The first two images are by Diego Velázquez and Francis Bacon, separated by four hundred years. Both represent Pope Innocent X in their paintings. Velázquez’s painting (1650) signals respect and obedience; he used paint and paint brushes. Bacon’s painting (1953) signals alienation and contempt; he used paint, sand, rags, garbage can covers, a photograph, but no paint brushes. The institution of the church is common to both images although with opposing attitudes. Other institutions also have authority figures. Joe Nalven represents (2008) a museum director as an authority figure; he used photography, digital editing and lamination on a distressed metal substrate. Nalven again represented an authority figure fifteen years later, but as a shaman. Each of these artists used different materials and techniques to achieve their imagery. The last image was created with the assistance of generative artificial intelligence with further postprocessing in an image editing program.

The question many ask is whether the last image is just the “next hill” in the making of art. The AI art takes a similar theme—authority figure—but uses a different toolset—generative artificial intelligence. Has some line been crossed? However we define that line, it appears to be something more than a human with a different toolset. This collaboration between human and technology is quite unlike that relationship in human art history. The GAI toolset plays too great a role in the image creation; the human artist merely supplied the text. Is this a step too far in what we expect in image creation?

The disciplinary approach—art history—maintains its coherence in accommodating different representational styles, materials, and technology in the first three images. However, the last image does not fit within that framework. The role of human authorship is questionable but potentially rectifiable with post-processing beyond the initial AI image generated. This discussion is entangled with other disciplines and what was viewed in the first two rooms.

Reflection

This art exhibit illustrates how the university process and structure can reintegrate academic silos with disciplinary integrity and, at the same time, become more permeable. The ever-expanding presence of LLMs are unlikely by themselves to significantly dissolve the academic silo. The conversation about how this change might occur suggests a unitary context—the art exhibition—distributed over three separate points of departure—the separate rooms.

In the absence of this type of transformation, one can imagine several alternatives.

Businesses may simply forego employees having a college degree. Technological knowledge can be obtained outside an academic setting—a trade school. Arguably, the un-siloing of academia can be deferred. For example, LLMs might be tailored to different departmental needs, based on funding sources, ideological practices—whether constitutional or not—privilege, paternalism and odd ways of virtue signaling. The writing is on the wall, and it is in Python. The questions become one of a new literacy and how to use that new language.

Editor’s Note: The visual content accompanying this article, including the cover photo, has been exclusively crafted by the author utilizing Photoshop Generative Fill, DALL·E 3, and Deep Dream Generator that transform text into images.

Push it further. AI can do a lot more than this, with a lot less genericism of the look.