“It is desirable, in short, that in things which do not primarily concern others, individuality should assert itself.”

—John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (London, 1859)

Jorge Luis Borges’s story “El Aleph” (1945) contemplates the struggle for personal liberty in Argentina, a subject he conjures more formally a year later in his essay “Nuestro pobre individualismo” (1946). Here I’ll analyze some of this prophetic story’s details with an eye toward bridging the gap between Borges’s vision of Argentine individualism after the Second World War and Thomas Jefferson’s vision of Virginian individualism before the American War of Independence.

The combinatory weirdness of Borges’s fiction is its beauty. But his fictions also survey sociopolitical dilemmas. As his protagonists and antagonists merge, they sometimes disclose ways to spread individualism while preserving the social fabric that sustains it. This is why I think Borges’s art offers a better way to discuss what we too often try to teach by way of boring (and often facile) historical, political, and economic treatises. Great literature has great utility.

Form relates to function where great literature is concerned. Borges didn’t write novels because he found them overbearing; “mucho ripio,” he said, ‘a lot of junk’ gets in the way of a good tale. “El Aleph” consumes a mere eleven pages of his Obras completas (617–28). Borges’s stories are dense narrative poems, not treatises with pat answers to life’s problems. They’re puzzles or, to use one of his favorite concepts, labyrinths. They invite decipherment. Unadventurous readers experience his fictions as existentialist nightmares, but attention to their allusions to liberty, property, and individualism transforms them into monuments to the tenets of classical liberalism.

“El Aleph” opens with epigraphs from Shakespeare and Hobbes, indicating Borges’s Anglo heritage and his relative isolation in Argentine culture. They also hark back to the religious militancy of the late Renaissance. When Protestant England disengaged from Rome, Catholic Spain became its main rival. That break was decisive. Although eighteenth-century Germany and France as well as early modern Italy and Spain spawned many liberal concepts, institutions, and practices, it was the more separatist English who saw to their jurisprudential dissemination.

Plaza Constitución, which the narrator associates with his memory of the death of Beatriz Viterbo, circles the juridical heart of “El Aleph.” It also signals Argentina’s rejection of an Anglo world with which it had so much contact in the nineteenth century. A supremely Dantesque lover, whose surname recalls a town north of Rome, dies just prior to a new advertising campaign for American cigarettes. From a liberal perspective, it’s the first of many melancholic setbacks in Argentina’s constitution (in both senses of this word). The second name of Beatriz’s cousin, Carlos Argentino Daneri—the narrator’s rival and alter—reiterates the national identity crisis.

The year of Beatriz’s death is also ominous. It heralds the “Infamous Decade,” when liberalism died in Argentina. The First Conference of the Communist Parties of Latin America was held in Buenos Aires, June 1–12, 1929. That winter the Great Depression spread fear and frustration, and the Argentine economy collapsed. The next year killings and bombings by anarchists angered moderates and conservatives, resulting in a coup d’état which replaced progressive president Hipólito Yrigoyen with Lieutenant General José Félix Uriburu. Argentina had been among the wealthiest countries in the world before 1929. By the time Borges wrote “El Aleph” the good times were over; and comparatively speaking it’s been downhill since.

The narrator describes Argentino as an elitist bureaucrat, the type whose mindset still dominates Argentina today: “Ejerce un no sé qué cargo subalterno en una biblioteca ilegible de los arrabales del Sur; es autoritario, pero también es ineficaz.” Argentino’s passion for French symbolist poetry adds a note of frivolity: “Su actividad mental es continua, apasionada, versátil y del todo insignificante.” Government-funded intellectuals are among the greatest poxes on society in France and Argentina. But there’s an important irony here. An intermittent confession by Borges punctuates the story as Argentino’s identity flits in and out with his own. Borges was after all not just a writer of fiction and essays but also a modernist poet and a librarian.

This self-directed irony grows when Argentino holds forth on “una vindicación del hombre moderno.” A list of innovations—telephones, cinemas, newspapers, streetlights—suggests the view that progress and wealth are spontaneous creations to be harvested rather than created. In this vein, Argentino inverts Francis Bacon’s fable of Mahomed going to meet the mountain when it doesn’t come to him: “las montañas, ahora, convergían sobre el moderno Mahoma.” Ominous are the allusion to an English philosopher and statesman—a contemporary of Shakespeare and Hobbes—and Argentino’s claim that things come to those who wait. Even more so is the rebirth of an archaic mass movement. Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Romantic authors like Bacon, Cervantes, Voltaire, Tocqueville, and Mill often juxtaposed civilization and the Muslim horde. Borges sees a similar dynamic in twentieth-century Argentina. The question is, of course, how do demographics affect political economy? As Jefferson warned: “An elective despotism was not the government we fought for” (Jefferson’s emphasis; see NSV, Query 13 and Federalist 48).

Epics are to archaic communities what written constitutions are to modern ones. They coordinate conflicts between individuals and crowds. Borges’s narrator tells Argentino he should write down his grandiose ideas. Argentino’s epic poem La Tierra offers up the literary trope of the “text within the text.” In theory, it’s that all-inclusive vindication of modern man which the narrator urges his rival to transcribe. The entire world as an epic poem sounds like fantasy or science fiction. But just as readers think Edgar Allan Poe wrote horror solely to frighten us, many mistake the strange surfaces of Borges’s texts for their content. In “El Aleph,” Argentino’s infinite perspectives on every point in the world insinuate the ultimate universal epic, a kind of global constitution. As such, the poem also allows readers metaphorical grounds for comparing the relative uniquenesses of nations and individuals.

Each person takes a special route toward, or away from, the expression of his individuality. Inevitably, and often tragically, the restraints imposed on him by his nation determine his path. If a paternalistic constitution grants citizens too many claims on the rest of society at the expense of everyone’s natural rights, then liberty is forfeited in favor of equality and welfare. Contemplating this tension between individual dignity and populist mandates, Borges follows in the footsteps of political theorists as diverse as Joseph de Maistre and Alexis de Tocqueville.

The French terms that pervade Argentino’s poem at this point—“el voyage que narro, es. . . autour de ma chambre”—refer to Xavier de Maistre’s Voyage Around My Room (1794), a text in which the younger brother of the great reactionary theorist validates his imagination while under house arrest in Turin for fighting an illegal duel. Argentino does likewise, it will be remembered, except that in the process he justifies everyone. Argentino’s (rather Parisian) universalizing modification of an intimate journey echoes Alexis de Tocqueville’s political labyrinth in De la démocratie en Amérique. Tocqueville’s faith in democracy as a global certainty is a liberal extension of De Maistre’s chambered nobility. The greatest theorist of modern democracy thinks a system of negative rights protecting personal liberty will eventually be shared by everyone, although their paths to it will be different: “They resemble travelers dispersed throughout a large forest where all the paths end at the same spot. … All nations which take not any particular man but man himself as the object of their studies and imitations will end up by adopting the same customs just as these travelers converge on that central point in the forest” (DA 2.3.17).

On the other hand, echoing De Maistre’s point that populist egalitarianism destroys grace, the narrator of “El Aleph” records another of Argentino’s verses in a footnote: “¡Olvidaron, cuitados, el factor HERMOSURA!” In the same note Argentino admits his anxiety about publishing La Tierra: “Sólo el temor de crearse un ejército de enemigos implacables y poderosos lo disuadió (me dijo) de publicar sin miedo el poema.” So, the note twice intimates something that remains unspeakable in public. On the one hand, if we don’t resist equality, we risk marginalizing beauty. On the other, there’s risk in granting liberty to the envious and resentful masses. People often vote for tyranny in order to destroy those who freed them in the first place.

The final verses quoted from Argentino’s epic deploy a neologism that mixes the colors of his nation’s flag with images of bones and sheep. Argentines know full well that the politics of fear and passive conformity can override a liberal constitution. What kills a nation is domestication.

Se aburre una osamenta —¿Color? Blanquiceleste—

Que da al corral de ovejas catadura de osario.

Politically charged ironies follow this sinister moment. Argentino’s denunciation of agrarian tedium “al rojo vivo” recalls the persecutions of peasants by Lenin and Stalin (and anticipates their bloody mobilization by Mao). The linguistic fluidity of “australiano” hails Australia but also a global South that includes Argentina, thereby insinuating the national tragedy of resistance to Anglo liberalism. Argentino’s fear that his austere verses might make readers trade optimism for cynicism—“herida en lo más íntimo el alma de incurable y negra melancolía”—implies the difficulty of a political system that rewards work and self-reliance instead of leisure and loyalty.

Let’s skip the rest of Borges’s junk—as wondrous and economical as it is—and get to the crux of the matter. A stark contrast now appears between Anglo and Latin sensibilities. Argentino invites the narrator to drink a glass of milk in a bar recently opened by Zunino and Zungri, who also happen to own Argentino’s house. Borges hints that legal traditions are intertwined with cultural norms, and Argentina’s are suboptimal. The narrator senses a crowd envious of others’ bounty: “en las mesas vecinas, el excitado público mencionaba las sumas invertidas sin regatear por Zunino y por Zungri.” And Argentino wants to drag him down to its level: “Mal de tu grado habrás de reconocer que este local se parangona con los más encopetados de Flores.”

After an inflationary expansion of his already baroque epic, Argentino opens a sidebar on prologues: “Acto continuo censuró la prologomanía, ‘de la que ya hizo mofa, en la donosa prefación del Quijote, el Príncipe de los Ingenios.’” Cervantes famously demolished a tradition of tumefactive preambles in Spanish literature. But acknowledging this recalls the bitter Anglo-Hispanic divorce that marked his career. Carroll B. Johnson, the great Hispanist at the University of California, Los Ángeles, once noted that Cervantes’s La española inglesa laments capitalism’s “stillborn” status in Spain circa 1605. In a forthcoming essay on María Zambrano and Cervantes in the Hayekian journal Cosmos + Taxis, Nayeli Riano distinguishes rather surgically between the English tradition of liberty as a matter of “political principles” and the Spanish tradition of liberty as a function of “literary and philosophical ideals.” Borges and his Aleph revolve around such contrasts between frameworks for growth and the stagnation of creative moralizing.

Hatred of entrepreneurs metastasizes over a glass of milk when the narrator learns that Argentino retains a stubbornly anachronistic concept of property: “Con tristeza y con ira balbuceó que esos ya ilimitados Zunino y Zungri, so pretexto de ampliar su desaforada confitería, iban a demoler su casa.” Again: “—¡La casa de mis padres, mi casa, la vieja casa inveterada de la calle Garay —repitió, quizá olvidando su pesar en la melodía.” In Argentino’s mind, the house is rightfully his because his family occupies it. If it’s to be turned into a bar, he believes he’s owed money: “Dijo que si Zunino y Zungri persistían en ese propósito absurdo, el doctor Zunni, su abogado, los demandaría ipso facto por daños y perjuicios y los obligaría a abonar cien mil nacionales.”

I now ratify my claim that form is married to function in great literature. At this precisely proprietary point, Borges unveils the titular symbol of his tale. Furthermore, we learn that the Aleph is what has allowed Argentino to write La Tierra: “Vaciló y con esa voz llana, impersonal, a que solemos recurrir para confiar algo muy íntimo, dijo que para terminar el poema le era indispensable la casa, pues en un ángulo del sótano había un Aleph. Aclaró que un Aleph es uno de los puntos del espacio que contiene todos los puntos.” Without access to this cabalistic object, Argentino knows his literary production will end. So, he eagerly—and retrospectively—claims it as his own: “Es mío, es mío: yo lo descubrí en la niñez, antes de la edad escolar. … ¡El niño no podía comprender que le fuera deparado ese privilegio para que el hombre burilara el poema!”

But Argentino has a problem. He found the (unmovable) Aleph in the basement of Zunino and Zungri’s property, so he must expropriate it from them. To do so, he subverts the liberal idea of property as a natural right by way of the positivist legal tradition of codified grants. Of course, he has a lawyer in mind who will make his case for him: “No me despojarán Zunino y Zungri, no y mil veces no. Código en mano, el doctor Zunni probará que es inajenable mi Aleph” (Borges’s emphasis). Argentino’s insistence on his “unalienable” right to the Aleph translates and echoes a famous word in the first sentence of the preamble of the founding document of the United States of America. All by itself, this word highlights the fundamental difference between the Anglo and Hispanic traditions. Anglo ears, including Borges’s, automatically hear Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” (my emphasis).

Now, there’s tremendous irony here. Property doesn’t figure in Jefferson’s list of unalienable rights. Looming large in Borges’s story is the Lockean ambiguity of whether Europeans claim property from nature or from others who might consider said property communal: “Corté, antes de que pudiera emitir una prohibición.” Per Defoe, a natural right to property is only possible on an uninhabited island, or else after an agreed system of tradable assets has been operative for some time. Even then, certain definitions of property remain tricky. What makes property public instead of private? What is intellectual property? What do we do about mineral rights? What about claims regarding the facts and significances of historical events?

The Aleph clearly echoes an alchemical fabrication under the Tagus River in Toledo written by don Juan Manuel circa 1335. (Borges later stated it recalled H. G. Wells’s “The Crystal Egg” of 1897. Nonsense!). The Aleph, however, also has all the markings of a sociopolitical enigma. Its metaphysical status targets the idea of ownership: “Sí, el lugar donde están, sin confundirse, todos los lugares del orbe, vistos desde todos los ángulos.” Again: “una esfera cuyo centro está en todas partes y la circunferencia en ninguna” (cf. Augustine and Emerson). When the narrator voices incredulity about this “infinite item,” Argentino’s response echoes criticism of the hypocrisy of Jefferson, a slave owner and pirate colonizer of Indian lands preaching universal human rights: “La verdad no penetra en un entendimiento rebelde.” This accords with Borges’s regard for Edgar Allan Poe, who also wrote ironical critiques of Jefferson (see “The Gold-Bug”).

We’re at the ultimate North–South divide, between the United States and the Confederacy, between Christian and Muslim Spain, between Anglo (Protestant) and Hispanic (Catholic) worlds. Here, too, the narrator—a bicultural projection of Borges—feels the heartache of a desire blocked by incomprehension and death: “… me asombró no haber comprendido hasta ese momento que Carlos Argentino era un loco. Todos esos Viterbo, por lo demás. . . Beatriz (yo mismo suelo repetirlo) era una mujer, una niña de una clarividencia casi implacable, pero había en ella negligencias, distracciones, desdenes, verdaderas crueldades, que tal vez reclamaban una explicación patológica.” But the author still wants contact with that other tradition, the one that fell behind after London’s divorce from Rome. Thus, before staring into the Aleph, the narrator voices tearful nostalgia before a discolored portrait of his lost love, finally revealing his name in the process: “—Beatriz, Beatriz Elena, Beatriz Elena Viterbo, Beatriz querida, Beatriz perdida para siempre, soy yo, soy Borges.” Homer, Dante, Petrarch, and Cervantes are a Mediterranean tradition just out of reach. Borges is forever divided, like liberalism itself, between the negative defensiveness of Anglo individualism and the amorous fidelity of Hispanic universalism.

All nations evince some form of this contrast. Argentino describes the Aleph as multum in parvo, “much in little,” the same impossibility as that early motto of the United States: e pluribus unum, “from many, one.” Moreover, the tension between equality and liberty has negative externalities either way it tips. Borges once described his story “El Congreso” as a mixture of Whitman and Kafka. American triumphalism and European horror might seem antithetical, but imperialistic expansion is hard to distinguish from totalitarian tyranny in the heat of a bloody battle in the Philippines. It depends on your point of view. This problem of violence surfaces as we approach the Aleph. Like a modern-day don Illán, Argentino instructs Borges over a glass of “seudo coñac” about how to position himself to view the Aleph. Down in the basement on his back, Borges considers the possibility he’s been poisoned. It’s not just a red herring or an allusion to Poe; it’s the juxtaposition of the ultimate social problem with a solution: “Carlos, para defender su delirio, para no saber que estaba loco, tenía que matarme. Sentí un confuso malestar, que traté de atribuir a la rigidez, y no a la operación de un narcótico. Cerré los ojos, los abrí. Entonces vi el Aleph.” In other words, one solution to the self-deceptions and paranoias that lead to violence is to experience the knowledge provided by the Aleph.

So, what does Borges see in the Aleph? A lot of junk, so much that it’s hard to know what to prioritize. But an indication of the liberal solutions of property, individualism, and liberty appears at a symbolic moment. Borges sees the masses in America, a silver spider’s web inside a pyramid, and a broken labyrinth that expressly represents London: “vi las muchedumbres de América, vi una plateada telaraña en el centro de una negra pirámide, vi un laberinto roto (era Londres).” Here’s the web of collectivism from which all people must emerge. One way to escape from a labyrinth is to break it. “El Aleph” signals Borges’s Anglo advice to Argentine readers. Break out of your maze. Look to London for other answers to sociopolitical questions. Unleash negative constitutional rights, tradable assets, and unique personalities. There’s nothing to fear, at least nothing more than what should be feared from hibernation and inertia.

Why is Buenos Aires not London? The size of the Aleph, its diameter “de dos o tres centímetros,” and its location under the stairs in a basement point to the reduced sphere of personal liberty in Argentina. Its contents amaze us, but they’re still locked away. The Aleph lacks the Romantic initiative of De Maistre surveilling his chamber, Jefferson or Mill forcing the social sphere away from individuals, or Emerson sending the self soaring off into ever-wider circles of the universe. The narrator also sees something broken in the Aleph: “vi un cáncer en el pecho.” I believe I’ve seen this too. Unlike Austin or Miami, Buenos Aires seems poorer than it was in 1984. This might be an illusion, a false Aleph, a cat in the wall, an X-ray. Argentina is a mixed economy, and pseudo-capitalist growth can be ugly compared to Rome or Madrid. Still, and although I can’t prove a negative, from my perspective she should be wealthier. I also read about Deputy Álvarez’s breast cancer long after I postulated its existence to a friend of mine from Caracas. He won’t remember. Should I worry about him? I think not. He has escaped that regime. Besides, I’ve seen a worse disease infecting the heart of the United States. A willingness to violate freedom of speech in the world’s most powerful nation is more worrisome than weak property rights in Latin America. We need to borrow an Aleph.

Borges is shaken when the Aleph reveals to him each point’s infinite individuality all at once. The implications are ironic and ideological. Depending on when Argentino last viewed the object, antagonist and protagonist have each seen everything on Earth from every perspective. Such transcendence is both intimate and universal. An impossible combination, like liberty and equality. The revelation sounds religious, anti-capitalist even: “Aunque te devanes los sesos, no me pagarás en un siglo esta revelación.” When Borges leaves Argentino’s house, he confronts the masses while retracing the story’s original plaza: “En la calle, en las escaleras de Constitución, en el subterráneo, me parecieron familiares todas las caras.” Echoing this populist vision, when Argentino later brags about winning a national literary contest, his choice of colors is leftist: “esta vez pude coronar mi bonete con la más roja de las plumas.”

On the other hand, the compounding effects of liberty over time are also unquantifiable and impossible to repay. Then there’s the fact that Borges gradually forgets what he saw in the Aleph. Forgetting our sameness forces us back to the asymmetrical logic of liberalism. Add the story’s use of such terms as “Constitución” and “inajenable,” and there’s something Virginian or Jeffersonian about the Aleph’s architecture: “¡Qué observatorio formidable, che Borges!”[1]

By way of all this back and forth, this “constitutional ambiguity,” Borges argues our different perspectives need each other. Reforming the compromises in the U.S. Constitution with the unrelenting universality of the Declaration of Independence, the American Civil War ended slavery and asserted an individual’s inalienability from himself. It took violence for America finally to incorporate a more Mediterranean form of liberalism. We might imagine the French halfway between Anglo and Hispanic traditions. According to De Maistre, equality threatens beauty; but per Rousseau, so does a purely transactional world. Borges knew untold beauty gets torn asunder by markets, like the sacred basement of Argentino’s house. Those new blonde cigarettes from the U.S. were thought to cause more cancer than traditional black tobacco.

Perhaps Borges’s Aleph contains a mix of Protestant and Catholic revelations, and they might be mutually helpful. The northern Puritans and southern pirates of the United States each had blind spots. In Thucydides, overly urban Athens and too rural Sparta were cursed in their own ways and attracted people persecuted by each other. Inverting Argentino’s hatred of agrarian tedium, Borges warns his rival to leave the city: “lo insté a aprovechar la demolición de la casa para alejarse de la perniciosa metrópoli, que a nadie ¡créame, que a nadie perdona.” There’s ancient wisdom here. There might also be a political plan for spreading liberty. The integration of Latin America could free citizens from the sociopolitical insanity of the metropolises that dominate their respective countries. When cities compete, they’re less likely to decay into madness.

Borges also allows a contingent view of nationalism. Rebels can be liberators and centrists can bring justice. It depends on circumstances and perspectives. Having lost his Aleph, Argentino’s writing improves: “Su afortunada pluma (no entorpecida ya por el Aleph) se ha consagrado a versificar los epítomes del doctor Acevedo Díaz.” In the English translation, Borges changed the epitomes of the radical Uruguayan author to “an epic on our national hero, General San Martín.” This emphasizes the Janus-like politics of the story. Wars of independence split allegiances within newly formed nations, and depending on the context and the issue, a centrist is preferable to a federalist. Another problem faced by Argentina (also Mexico, Venezuela, and others) is that its struggle for independence from Spain gets muddled by struggles against Anglo imperialists. It’s difficult to embrace an individualism associated with an enemy. But maybe that’s not always bad. Today, I’m willing to thank a Catholic God that Chile is unlike Illinois. Appropriately enough, there’s a statue of General San Martín in the Foggy Bottom of Washington, D.C.

Finally, our failing memories save us from the insanity of our own contradictions. My mother can’t recall that angered by Watergate she voted for Carter, even though she thought Nixon’s trip to China was a great idea. The once anti-war Left in the U.S. now wants to push Russia back to Volgograd. Borges broaches such cognitive dissonances repeatedly in “El Aleph.” The last case is the most heartbreaking: “Nuestra mente es porosa para el olvido; yo mismo estoy falseando y perdiendo, bajo la trágica erosión de los años, los rasgos de Beatriz.” Aside from Emma Zunz, Borges’s fiction lacks serious females. To his credit, he recognized this. His devotion to Beatriz dovetails with his dedication of “El Aleph” to Estela Canto. In the wake of an epic song, abasement before a woman manifests the original gesture of freedom in all cultures. One way to escape a labyrinth is to break it and imitate London. But only Elizabeth I could redeem Henry VIII’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon. Which is to say you should still hold onto the thread Ariadne gave you. Besides, exiting one labyrinth we enter another; nor can you go around the world breaking them all. Estela and Borges show us that the Hispanic and Anglo worlds need each other to solve our problems. Sometimes we have too little freedom, sometimes too much.

[1] I’m told Professor Jared Loewenstein was most responsible for convincing the University of Virginia to purchase what is now the Borges Collection at Alderman Library. We should also note that “Mr. Jefferson’s University” was founded in 1819 and that the United States recognized the independence of the former Spanish colonies in 1820.

Photo by Rafael Leão on Unsplash

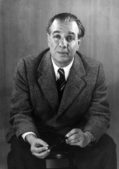

Inserted photo by Grete Stern – http://www.me.gov.ar/efeme/jlborges/1951-1960.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4529935

I have no doubt you are correct. The opposition is from Tocqueville. I think slavers might qualify is relatively greater pirates, but my point is simply that Borges was very interested in his Anglo brethren, pirates, puritans, and otherwise. Argentines have a chance to embrace their inner pirates. Let’s hope they take it. There are Catholic puritans as well.

“The northern Puritans and southern pirates of the United States.”

Ummm, there were also northern pirates — these were my ancestors.

First, geography. The Gulf of Maine is a bowl — it is 270 miles if you go straight across the ocean from Boston to Yarmouth at the tip of Nova Scotia (Canada) and 660 miles if you go by road — and likely a few hundred miles more if you followed the coast. The mountain ranges in New England run roughly from the Northwest to Southeast, and they continue in that direction offshore, with underwater mountains coming up out of the deep. And it is one of the foggiest places in the world.

After the Revolution, the British were in Nova Scotia (principally Halifax) and the Americans in Boston, without a whole lot of any law in between. The islands of Penobscot Bay and the Maine coastline further DownEast were partially settled by “retired” pirates — they even had a Pirate’s Old Age Home in Machias (ME). And the other thing to remember is that a lot of the Loyalists — expelled from Massachusetts under penalty of “death without benefit of clergy” didn’t all leave. A lot instead went to Maine where the locals didn’t much like the Boston Puritans anyway, and could have cared less that their otherwise decent neighbors had managed to offend them.

As to “piracy” — Hollywood style — I don’t know. But I do know that as late as the 1920s there were ships running aground on the many ledges and that anything of value was scavenged from these ships. I’ve sat in a rocking chair that was reportedly taken from one ship and been in a former schoolhouse that was reportedly built out of the timber from another. And there are a lot of other stories that I don’t intend to repeat here or elsewhere.

My point is that the Northern Puritans were a whole lot more complicated than many realize.