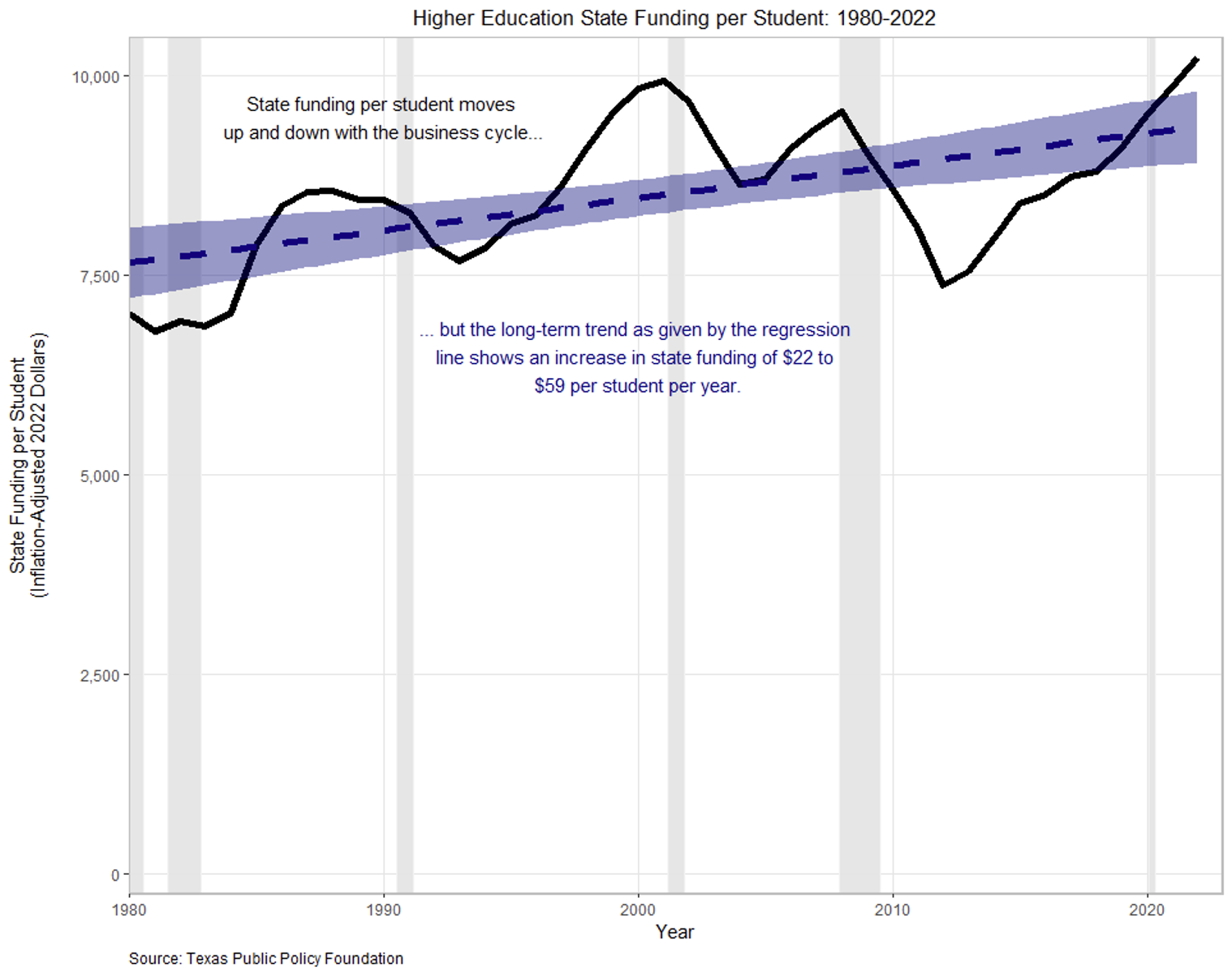

One of the key stories in higher education finance is so-called “state disinvestment,” which alleges that states have made relentless cuts to college and university funding. But state disinvestment is a myth—states have not, in fact, disinvested in higher education. In this debate, a picture is worth a thousand words, so here is a figure (copied from a new report) showing per-student state funding for higher education over the past forty-two years, adjusted for inflation:

Disinvestment implies a downward slope, yet the slope of the line is clearly upward, meaning that states have actually increased funding for colleges and universities over time (by $22 to $59 per student per year). In fact, in 2022 (the most recent year with data), state funding was the highest ever recorded. Needless to say, setting funding records is inconsistent with a story of decades-long state disinvestment.

The evidence debunking state disinvestment isn’t new (see here and here), and yet the myth persists. In fact, it is rare that a week goes by where I don’t read about state disinvestment stated as fact. For example, Neal Hutchens and Frank Fernandez, professors of educational policy studies and evaluation and higher education administration and policy, respectively, recently wrote, “there has been a sustained longer-term trend of lower funding from states for their public colleges and universities.” Similarly, Kevin R. McClure and Barrett J. Taylor, professors of higher education, advocate “doing what it takes to secure the revenue needed to make up for state funding cuts.”

I highlight these scholars because their specialty is higher education or education policy, so the fact that they don’t recognize that state funding is trending up rather than down is bizarre. It would be like an economist arguing that we’ve recently been suffering from deflation rather than inflation.

The widespread belief in the state disinvestment myth is severely distorting public policy as well. For example, West Virginia University is cutting back, which includes laying off some tenured faculty. Liam Knox reports:

Neither Gee nor Reed placed much emphasis on the role of state disinvestment in creating WVU’s budget problems, an omission that [Kelly Allen, executive director of the nonprofit West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy] said was curious. West Virginia’s state funding for higher education has decreased by over 25 percent in the past decade, according to a Center for Budget and Policy study.

“They are truly selling state disinvestment short; that’s the primary reason for these budget shortfalls, not these universal problems,” Allen said.

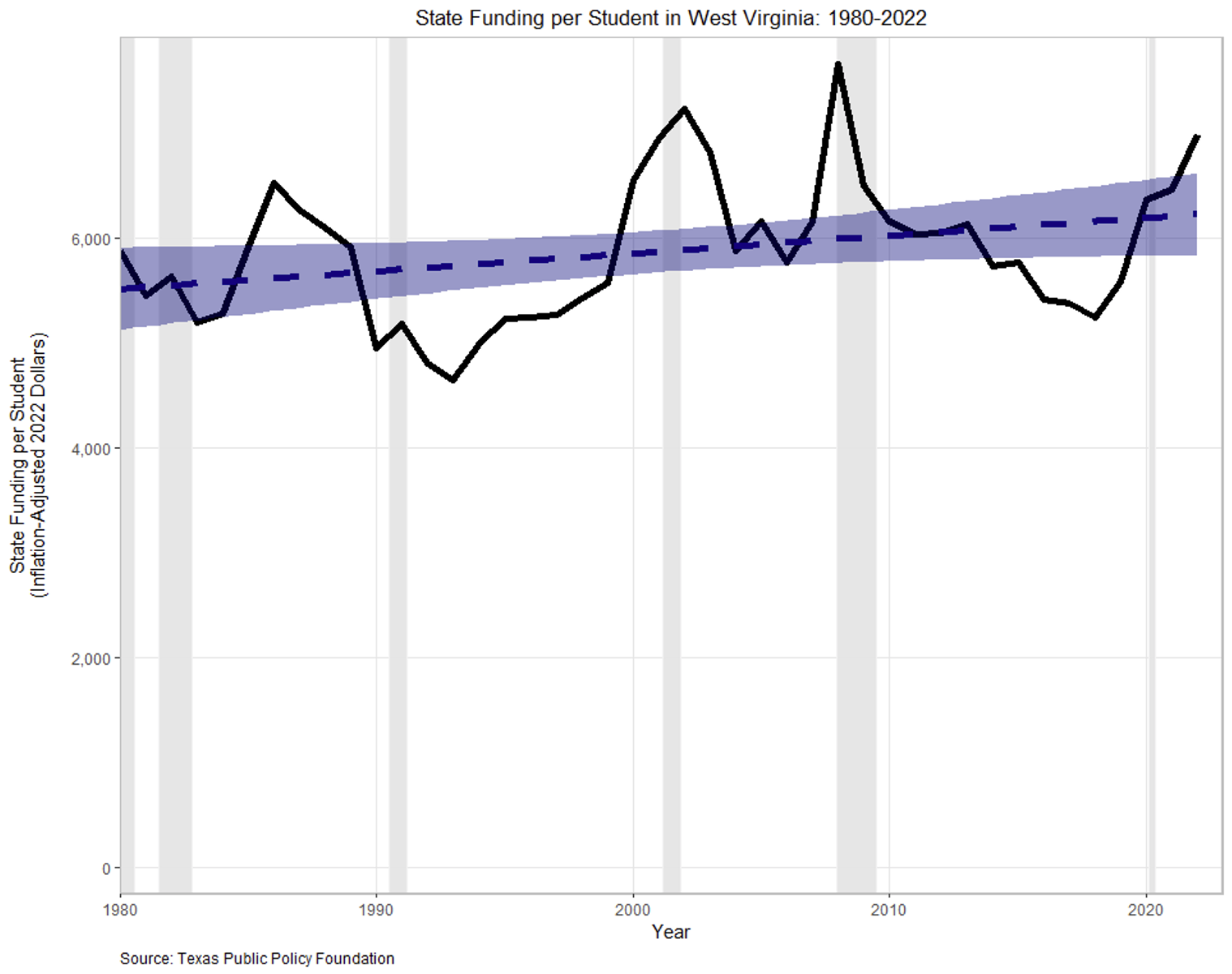

But is West Virginia guilty of state disinvestment? No. Here’s per-student state funding in West Virginia since 1980:

The trend line is slightly up, not down, which means that state disinvestment is a myth for West Virginia, too. There is simply no truth to Allen’s claim that the real cause of the cuts at WVU is state disinvestment. The state has not been disinvesting, and even if WVU’s allocation is lower, the issue would be the reallocation of funding among colleges and universities rather than disinvestment.

[More from Andrew Gillen: “Congressional Republicans Step Up to the Plate”]

There are a few reasons why so many otherwise smart people are making such a basic mistake.

First, there’s confirmation bias. Because it is impossible to read much about higher education finance without seeing state disinvestment stated as fact by otherwise reputable people, most will simply adopt “state disinvestment is true” as the conventional wisdom, requiring little if any supporting evidence.

Second, there are, indeed, times when states do cut funding, usually around recessions. By cherry-picking the comparison dates, one can almost always find a time period that shows a decline, which seems to confirm state disinvestment. For example, even though four decades of data show no state disinvestment in West Virginia, funding really is lower in 2022 than it was in 2008. But the problem with cherry-picking is that it doesn’t yield reliable results—it selectively chooses evidence that supports a predetermined conclusion, rather than considering all the available evidence to draw more accurate conclusions.

Third, many fail to adjust for inflation. Any comparison of the value of a dollar today to a dollar four decades ago hinges on adjusting for inflation correctly. Unfortunately, an influential report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO) association does not adjust for inflation. Rather than following established standards and using a legitimate price index, SHEEO uses a custom-made one called the Higher Education Cost Adjustment (HECA), which adjusts for estimated costs. Yet the HECA severely overstates inflation. As I noted in a new report,

The HECA adjustment thus overestimates state funding in 1980 by over 36%, more than $2,500. By massively overstating past funding, HECA is heavily biased toward finding state disinvestment. This bias is so strong that even if state funding increased by $2,500 per student, the HECA adjustment would falsely record that as a decline.

Here’s the bottom line: while higher education is suffering from many problems, state disinvestment isn’t one of them. It’s time to leave this myth in the dustbin of history.

Image: Adobe Stock

There are two concurrent factors at play here — public universities are inexorably expanding their expenses while the number of 18-year-olds is starting to decline, in some states already has.

UMass is a good example of the first factor, with people crying how the Commonwealth now only funds about a fifth of the total budget when the state used to pay more than half — it’s not that the legislature is allocating less (it’s actually allocating more) but that the total sum that UMass spends has increased so much.

When the legislature had to impose a mid-year budget cut in 1989, UMass imposed an emergency fee to make up the difference, what then became a “curriculum fee” as the university got less than it wished over the next few budget cycles — but when the funding levels of prior years returned a decade later, the “curriculum fee” remained. When the dot-com bubble burst and allocations were lean, this fee was matched with another new fee, I forget what that one was called — both remained when more generous funding returned, only to have the same thing happen again when the economy tanked in 2008. So now in FY-24, some 35 years later, the legislature’s larger allocation represents a smaller portion of the total sum.

Maine is an example of the other problem — long a state where educated young people have to move out of state to find work, most of Gen X moved to Greater Boston. K-12 had something like a 10%-15% reduction in headcount since 2000, and these are the students that the state is now willing to subsidize attending UMaine. Except that there aren’t enough students to fill the seats so UMaine is offering discounts to out of state students

That’s all fine and good — in terms of bond underwriting, it is a necessity, but the legislature is still allocating on the basis of the out-of-state students paying full price and hence is paying for fewer students than the institution actually has.

Come the abyss — Fall 2026 when the babies not born in 2008 won’t be going to college — I suspect that a lot of state legislatures will shift more toward a headcount allocation — if there are a third fewer students on campus, expect for a third of your allocation to disappear next year…

And what’s not mentioned in any of this is what would happen if both the state and federal governments actually started cutting the higher ed largess. Perhaps because higher ed isn’t valued by as many people as it once was — an interesting article in the NY Post: https://nypost.com/2023/08/16/why-college-has-become-a-total-ripoff/

Thanks for writing this. The reflexive default of many academics to “moar state funding = moar gooder” prevents us making even very obvious strategic alliances with the public that provides the lion’s share of higher education funding.

What academics ought to say to the public is: “you already give us enough money, more than enough money! Taxpayers are generous and we are grateful! You don’t need to throw more money at us, our paws are not out. The problem we face is how the money is allocated after it leaves you and you think it reaches us. An ever-growing proportion of it is monopolized by central administration, so students and faculty never see it.”

If academics said to the public: “DON’T GIVE US MORE MONEY, help us wrest it from administrators”, we’d find a zillion taxpayer allies. Instead the most activist academics are constantly fantasizing about going on strikes in order to demand more from the public (and only rarely direct their demands at admin, the ranks of which they often aspire to join).

Faculty are not innocent here — in the 1950s, they taught SIX days a week (the 90 minute Tuesday/Thursday classes were actually 50 minute classes that also met on Saturdays) and they taught a 17 week semester exclusive of finals.

We now sometimes have a 13 week fall semester…

Faculty used to teach 4+4 or 8 classes a year. Now it’s 2+2 or only four classes a year, with many teaching less because they get release time. And faculty pay, adjusted for inflation, is vastly more lucrative than it once was…

Not at my public university. The state cut millions from the annual budget. Maybe the fact in the past 5 years the student enrollment has dropped more that 15% has something to do with it. Tenured faculty positions were also chopped.

The question I would ask is dollars per scholar, adjusted for inflation.

“Yet the HECA severely overstates inflation.”

Well, it depends. As a highly labor intensive enterprise, higher education of course is going to have costs that rise faster than the standard CPI rate. (See Baumol.) Guess what, the professors still expect to have health insurance, which is rising a lot faster than CPI. And at least at public universities, it’s hard to tell the janitors that they shouldn’t get the same benefits.

And even apart from benefits, it’s well-known that in our recent capitalist economy, salaries for highly trained professionals — including professors and officials in higher education — are rising faster than the general run of wages. Not by a whole lot, but it adds up over time.

And these data about state funding change depending on how you choose the time window. Here’s a figure for 1990 – 2015 showing state funding per student decreasing somewhat over time:

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/06/28/higher-education-cost-adjustment-under-fire-again

The source? One Andrew Gillen.

Bottom line: state appropriations are covering less of the cost, tuition more. CPI adjusted costs are rising something like 1% per year. About what one would expect. Probably a little on the low side compared to what it should be. Don’t believe it? Imagine running your local school — public, private — on a 1955 budget. You will be shocked at how much costs have increased. As one would expect in a growing economy with rising wealth and income.

Your sense of entitlement is jaw dropping….

“Guess what, the professors still expect to have health insurance, which is rising a lot faster than CPI.

The professors can expect whatever they want to expect, that doesn’t mean that they are going to get it for free. Say what you want about capitalism, no university could exist today in a truly capitalist environment because professor compensation, including their benefits, vastly exceeds the value of their labor

“And at least at public universities, it’s hard to tell the janitors that they shouldn’t get the same benefits.” As there are a LOT of students who would LOVE to do their jobs without any benefits, it’s about time we started. FIRE the janitors and hire the students!!!

It the real world, people are paying a lot more for their health insurance than they used to (Thanks Obama!) — faculty seem to think that they somehow are entitled to be exempt from the economic realities that everyone else has to live with.

“Here’s a figure for 1990 – 2015 showing state funding per student decreasing somewhat over time: “

That’s called “cherrypicking.”

“Imagine running your local school — public, private — on a 1955 budget. You will be shocked at how much costs have increased.”

No, what’s more shocking is the massive decrease in labor productivity. The MASSIVE decrease…..

Rave on, Doc.

I will just point out, again, that the figure for which you accused me of cherry picking, was created and published by Andrew Gillen!

What you fail to understand, Jonathan, is that the federal and state governments can impose REAL budget cuts that would make this statistical variance irrelevant, and I suspect they soon will.

Let me give you two historical examples.

The first is the Apollo Project — the space race. After the moon landing, there was *bipartisan* support to vastly cut NASA’s budget, the Dems wanting to spend the money on cities and Nixon wanting to pay down Vietnam-fueled budget deficits. So in 1970 NASA went from 4% to 0.25% of the Federal budget. Throw in the 1971 ending of funding for the Boeing 2707 supersonic passenger plane and other DOD cuts and there were major layoffs in the aerospace industry, the likes of which no one had ever anticipated.

A decade later, we shut down all of our mental hospitals and schools for the mentally retarded. There were civil rights lawsuits, there were all kinds of new psych drugs, and there were noble plans of community placements — I’m not getting into why we did it or all the things that went wrong — I’m simply saying that we literally abandoned billions of dollars worth of perfectly good buildings — with everyone who had been working in them having to find new employment somewhere else.

You can talk about statistical variance while I warn that our state and federal governments could (and likely will) do the same thing to our state universities — with the added incentive of unlike the asylums built in the late 19th Century, the buildings academia built in the 1960s are literally falling apart.

Remember the fate of the Apollo Program (which proposed landing on Mars in the 1980s) — the Democrats wanted money instead for the cities, and the Republicans wanted money instead to reduce the deficit — and hence there was bipartisan agreement to not spend it on NASA.

That’s going to happen to higher ed….