From November 10 to 13, I attended the annual meeting of the American Anthropological Association (AAA), which was held in Seattle, Washington. The AAA is the largest anthropological association in the world. It is a scholarly and professional organization, and three-quarters of its members are academics—either professors or students.

The AAA, unlike the other major anthropological associations, covers all four fields of anthropology: cultural, linguistic, physical, and archaeological. One might, thus, expect sessions that combined these four fields, but the session titled “Seeking Continuity in a Dynamic Discipline: Scientific Anthropology’s Traditional Four Fields,” in which I presented with linguist Glynn Custred, archaeologist Timothy Ives, and cultural anthropologists Roland Alum and Christopher Hallpike, was the only four-field session in the entire conference. My own area of research is best described as physical anthropology: I study skeletal remains from archaeological sites.

I was looking forward to attending the conference, since this would have been the first large conference that I attended in person since the beginning of COVID. I also had the great pleasure of meeting Glynn Custred and Timothy Ives in person. Yet, unfortunately, the conference’s hybrid setup, which included virtual on-demand sessions, live-streaming sessions, and live sessions, seemed to have thinned out the crowds, and none of the sessions were particularly well attended. Sunday’s sessions, which are always emptier than usual, were downright destitute.

Me and retired professor of linguistic anthropology Glynn Custred.

I made a special effort to attend sessions each day, looking specifically for sessions that dealt with human remains. However, if I had thought that there may be some interesting physical or archaeological sessions to attend, I was quickly disabused of that notion.

There were many red flags indicating that this conference would have a greater emphasis on the political trends of anti-colonialism, indigenous knowledge, and atonement for past behavior. For instance, there were nearly eighty sessions that used the keyword “decolonization” and over seventy sessions that used the term “white supremacy” (none of these were ethnographic studies on actual white supremacist groups, such as the Aryan Brotherhood). Session titles included:

• “Pronouns, Bottoms, Cat-Ears And Cuerpes, Girl: For An Intersectional Trans Linguistic Anthropology”

• “Unsettling Whiteness: Race And Religion In The United States”

• “On Indigenous People’s Terms: Unsettling Landscapes Through Remapping Practices”

• “Unsettling Queer Anthropology: Critical Genealogies and Decolonizing Futures”

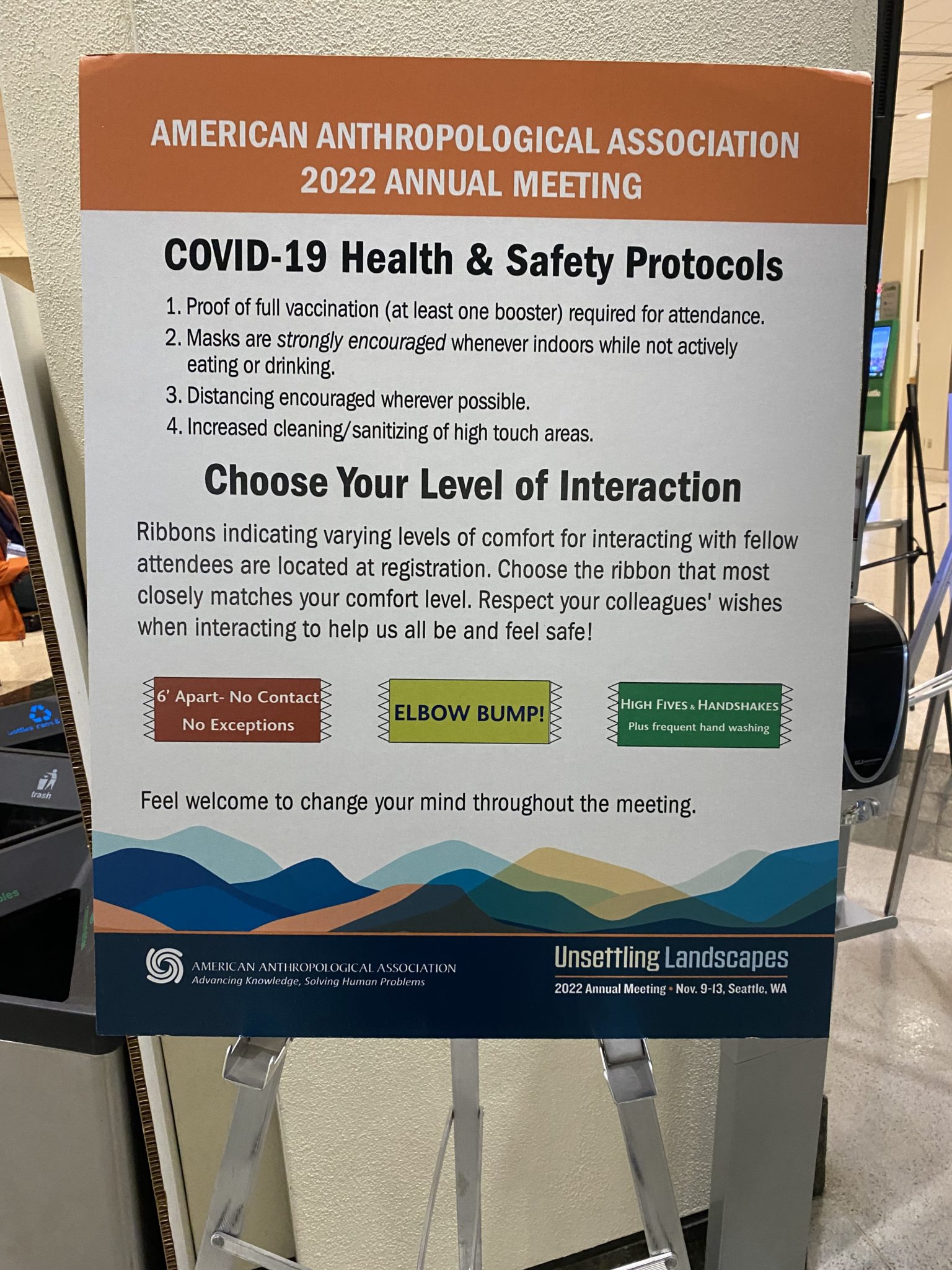

At registration, you could ask for a “comfort ribbon” to indicate whether you preferred 1) handshakes, 2) elbow bumps, or 3) six feet of distance between you and others. The list of “the AAA Principles of Professional Responsibility,” which was prominently posted at entrances, starts with the line: “Do No Harm.” There were also signs stating that attendees shouldn’t use “scented personal care products” to ensure that those with “chemical sensitivities” could attend the conference in comfort.

COVID precautions and comfort ribbons.

One particularly ironic talk was about online mothers’ groups whose members teach their children to have bodily autonomy to be able to say no to relatives’ physical affection (such as a grandmother’s hug or kiss). Her research basically involved joining an online group and teaching her own son that it is okay to say no to affection—this type of ‘anthropology of the self’ is a new and disappointing trend. (Most famously, it included a paper in which an anthropologist kept a masturbation diary about his self-pleasure while viewing Japanese anime-pornography. Another such example, in which an anthropologist wrote about her yoga exercises, was published in Anthropology News.) Yet, the anthropologist-mother was aghast when, after COVID-related isolation, her toddler did not seem to want affection from black people. She worried that her son was racist, but the leader of the online mother group she joined tried to reassure her that the child was just young and would grow out of it!

Many speakers began by describing themselves—ostensibly to make the sessions more accessible for the visually impaired—stating their hair color, their skin color, what they were wearing (some of whom got this wrong!), their height (some of whom exaggerated their height!), and, of course, their pronouns. For instance, in the session titled “Unsettling Whiteness: Race And Religion In The United States,” Nalika Gajaweera began by stating, “I’m a woman of South Asian descent. I have brown skin and black longish hair. I’m wearing a gray jacket [but she was actually wearing a yellow top], glasses and brown slacks. My pronouns are she/her.” Ironically, this was sometimes the most interesting thing these people had to say!

[Related: “Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow”]

On Wednesday, I attended a session titled “Unsettling Legacies In And Of Biological Anthropology’s Landscape.” This session—which started with a “Land Back Acknowledgement” explaining the history of the land on which the conference was held and the supposed continued colonization of the land—contained the only interesting talk that I saw at the AAA conference. This talk was on the analysis of hair to reconstruct past lives, such as those of the Capa Cocha children who were sacrificed 500–700 years ago by the Inca in Peru. Benjamin Schaefer, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois Chicago and The Field Museum of Natural History, discussed how hair can reveal stress levels through an examination of its cortisol and other hormones. By looking at where on the shaft this change in hormone levels occurs, one can estimate how long before death the stress affected the deceased. His conclusion was that the Capa Cocha sacrifices were extremely stressful events, equivalent to a major stroke, which contradicts the narrative that these children were treated royally and went peacefully. He further assessed that the sacrifices occurred when the populations themselves were dealing with stresses, such as famines.

Yet, Schaefer’s “content warnings” distracted from the interesting science he presented. He had a yellow star on the corner of certain slides to indicate that the next slide would contain images of human remains (and, thus, that we could look away if these images were disturbing to us). Yet, often the images of human remains did not come right after a slide with a yellow star (which was a little disappointing, as I was looking forward to seeing the next mummy). Furthermore, he began the talk by discussing the movement to end hair discrimination, which was completely irrelevant to his topic. I’ve written about Harvard’s repatriation of hair and how this results in the loss of yet another way to understand the past. Schaefer’s work illustrates the importance of this type of data; I can imagine that it may also be useful in forensics.

Ryan Harrod, who was at the University of Alaska Anchorage and is now dean of academic affairs and chief academic officer at Garrett College, was once a favorite researcher of mine. His research on the bioarchaeology of violence, which examined the skeletal evidence of violence with a focus on Southwest Native American cultures, such as the Pueblo and Aztec Indians, was fascinating work that combined skeletal analyses with environmental effects to look at the bigger picture of pre-Colonial interpersonal aggression. Thus, his talk was perhaps the most disappointing of all. He did not show any photos and lamented that his photos of human remains showing evidence of violence had been published in a variety of books and articles. His “reflexive” talk was a mea culpa for the ‘past sins’ of conducting research of which Native Americans do not approve. Although his talk was meant to center on missing human remains from the early twentieth century that never made it to museums, his focus was really on apologizing for his past work on violence, status, and resilience—which he said were big-picture questions that enabled him to get publications and tenure.

Upon asking Native American tribal members, such as Zuni elders, what they want anthropologists to do, Harrod learned that the Native Americans are interested in learning about “each individual,” not just the interesting individuals. They are definitely not interested in learning about past acts of violence. The elders provide most of the information on the remains, since if there is no pathology, trauma, or other interesting variant, anthropologists are at a loss to say much about the remains beyond sex and age. Harrod noted that he will likely not be able to publish his new work, but as he said, “I feel less guilty!” This cowardly approach saps anthropology of the interesting stories that the past can tell us and replaces them with mundane tales from elders that have no bearing on past lives. One wonders why Harrod made this startling turn-around and whether his movement to a community college reflected his atonement.

In the session titled “(Dis)Placing The Dead, (Un)Earthing The Truth: The Politics Of Death, Graves And Grief,” Leslie Sabiston, a professor at McGill University, discussed missing indigenous Canadians from recent history to the present. Although his abstract noted that archaeological remains would also be covered, he really did not address this issue, besides pointing to the close location and layout of an archaeological site.

In his talk, Sabiston tried to connect the “255 surreptitious burials” associated with the residential Indian schools in Kamloops, British Columbia, with current deaths and missing indigenous young adults in Canada. Sabiston’s bias against residential schools was evident, especially in the question-and-answer period. He said, “the whole reason for residential schools is to destroy indigenous life.” Although there is no evidence of any suspicious graves associated with Kamloops residential school, Sabiston noted that the ground-penetrating radar (GPR), which he claims is now a sacred tool imbued with ancestral knowledge, has shown anthropologists where the graves are. Thus, the ancestors are guiding the GPR to find the graves and are using it to talk to the anthropologists!

Asking for evidence of bodies, according to Sabiston, plays to “right-wing pundits.” Never mind the fact that not a single individual has been excavated. There is also evidence that the ground disturbances are not grave-related. And, if there are bodies that were surreptitiously buried, then some of these burial sites would be considered crime scenes, since they didn’t happen all that long ago (perhaps as recently as the early 1980s). Murder cases going back decades are solved regularly, especially with advances in DNA technology. Yet, if one questions the validity of claims regarding clandestine graves, Sabiston’s response is that “skepticism is violence.”

[Related: “Scholarship Versus Racial Identity in Anthropology”]

In her talk on missing and deceased people in Mexico, Marina Alamo Bryan, a PhD student at Columbia University, gave some startling statistics: since 2006, 100,000 people have gone missing in Mexico. In 2014, 43 students were captured and murdered in Mexico through collusion between the police and the cartel. These tragic circumstances should be studied by both forensic anthropologists and cultural anthropologists, to dissect how such events can be prevented. Bryan’s talk, however, took an ‘artistic’ approach. Instead of examining the remains or sites through forensic methods, and instead of providing us with narratives from the grieving mothers, Bryan showed us three sonographs: one from a rooster’s crow at a mass grave site, one from the sound of protestors, and one of onions frying at the church where searchers gather. This is the new anthropology—an avoidance of meaningful images and hard questions—which leads to inane research devoid of meaning.

In the session titled “Co-Creating An Anti-Colonial Cultural Sector,” speakers discussed their efforts to “decolonize” museums through repatriation efforts in Hawaii, Colorado, and British Columbia. In each of these cases, the speakers accused the museums of causing emotional pain to indigenous people, continuing colonial activities, and serving as institutes of “white supremacy.” In the case of the Hawaiian tribes, Halena Kapuni-Reynolds, a PhD candidate at the University of Hawaii, noted that decolonizing collections lays bare the “colonial harms.” One indigenous collaborator he quoted said that “work for the non-indigenous is to get up every day and contribute to healing our field,” and that the indigenous should be able to take multiple days off to cope with the trauma of working with these collections. The same collaborator noted that it is not enough to “comply with the law” regarding repatriation.

But it isn’t just the repatriation of artifacts and bones. Emily Leischner, PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia, talked of ceding audio recordings made by the Bella Coola (or Nuxalk) of British Columbia. Leischner, who described herself as a “white settler” from a “multigeneration of settlers [and] ancestor-farmers,” noted that captured audio (even when the indigenous sold these recordings) evinces an “extraction mindset” akin to mining resources from the land. In her work with the Nuxalk, Leischner decided not to record any of the interviews, so as not to continue the legacy of extraction. An audience member voiced the concern that when we lose the ability to collect data, we have gone too far, and that we are “throwing out the baby with the bathwater.”

It’s interesting to note that speakers discussed the financial gains for the tribes and the high price of returning items. For instance, to bring one hat and one ‘talking stick’ to an indigenous community within driving distance of the museum costs around $10,000. Jennifer Kramer, a professor at the University of British Columbia, said that returning materials, such as coming-of-age garb, is essential because the indigenous tribes don’t know what the garb should look like, even though the materials have only been gone for less than eighty years in some cases. What happened to the rich oral traditions that helped the indigenous reconstruct the past better than anthropologists can?

In British Columbia, the indigenous community has control over funds, and it is the anthropologists who must ask for reimbursements. The money ends up in the indigenous communities, so it is no wonder that one indigenous collaborator noted that anthropologists can never finish the process of redressing the harms caused by the museums. Most disturbingly, Leischner acknowledged that the Nuxalk are “constantly reinterpreting” what is sacred, what is important, and, therefore, what will be taken out of museums and delivered to the tribes at exorbitant prices.

It seems as if anthropology lies in ruins. Much has gone into the demolition work, including talks about oneself, an avoidance of traditional scientific methods, a lack of imagery, a preoccupation with current political fads, and a self-hatred of the field’s history. Even the opening-night keynote speakers, Antone Minthorn and Colin Fogarty, are not anthropologists. Minthorn practically just read his resume, and Fogarty talked about art. One must ask: was Antone Minthorn’s only necessary qualification the fact that he is Native American?

Next year’s conference doesn’t promise much better. With the theme of “Transitions,” we can be sure that the transitions in question are those of transgender people rather than the cultural, evolutionary, temporal, or linguistic transitions of traditional anthropology.

Image: Adobe Stock

Hmmm, I wonder if there’s anything to the fact that several of these scholars work in an entirely different nation that has an entirely different colonial history and entirely different ways of addressing the present moment? Perhaps there is something interesting in all of that? Hmmm, I wonder if the civil rights movement (in the USA) generated many changes in academic vocabularies and practices?

Anthropology has now made itself into a non-discipline in which there are no standards except the standard of viewing the history of anthropology as an endeavor aimed at promoting the cleansing of whatever is the current demon recognized by those claiming they are purifying anthropology of its past ills by writing gobbledygook as if this is the new anthropology, devoid of past ills. But this is not just what is happening in anthropology. Anthropologists of today are, if anything, just a more extreme form of what is happening in the larger society as they are providing what they promote with the veneer of academic respectability. How does anthropology cleanse itself of the non-subject promoted by today’s anthropologists?

Very disappointing to see this. Anthro has been on the decline for decades because of the partisan bickering that is reflected in the article. Anthro has NEVER been an apolitical field, never has been, never will be. By its very nature, it is one of the MOST politically based academic disciplines in HE. The not so subtle mockery and incredulity that you exhibit and then posit in the article is your opinion, which you have a right to. Why not just say what you really mean. You feel more comfortable with the young republicans than the others and just continue the open warfare that has decimated the disciplines instead of working towards understanding to get important things done.

I’m not an anthropologist, but I was triggered by uour comment enough to ask: are you freaking kiddding me? Are anthropologists all infected with lack of self-awareness?

You decry anthropology’s decline and then ably demonstrate a vivid example of why that decline has happened.

It’s very sad to see most forms of education sliding down these political paths. We are rewriting truths with agendas and teaching the next generations half truths on top of political lies.

This is how societies crumble, we are seeing history actively erased.

For some context, Elizabeth Weiss was locked out of research materials from her own place of employment because she was a racist and unprofessional, so much so that her department literally held a panel called “What to Do When One of Your Tenured Professors is a Racist”. She’s been called out for being unprofessional by multiple anthropological organizations and a number of other experts in her field.

You can take the redneck out of Arkansas….

Did Ms. Weiss offer a defense to the charges? Tell us more about yourself, Billy.

Let me guess, she was labelled “racist and unprofessional” for speaking exactly the sort of truths that she has here? That is indeed revealing, but not in the way you think.

Hey Rube!

This Rubin guy is so “trivial”. Just because Weiss got her Ph. D. in anthropology from the University of Arkansas, it doesn’t follow that she is a so-called “red neck” (standard name calling “move” of modern “ad hominem-ing” bogus critics) who comes from Arkansas. Her undergraduate degree in anthropology was from California Santa Cruz and her masters degree was from California State University at Sacramento. So she sounds like a “California Girl”, with a high I.Q., rather than an Arkansas “red neck” — not that there is anything wrong with farmers who have red necks from farming and thereby enabling wind-bag “elites” to eat food.

Weiss wrote a couple of books with which her dim-wit (woke?) colleagues disagreed and the best “criticism” that they could devise was that she was a “racist” for asserting that (and also proving) that indigenous activists and their political “allies” are anti-science obscurantists, as well as destructive towards archeological artifacts. Thus the title of one of those books mentioned above, to wit: “Repatriation and erasing the past.”

The triviality with respect to grammar is so obvious. These “woke-jokesters” profess absolute antipathy to “patriarchies”, but they want their allegedly “own” cultural artifacts re-“patriated”, so that they can destroy them!

What do these petty reactionaries do, when they are called on their neo-Luddite agendas? They lock the doors on her collection of archeological human artifacts and “ad hominem” her as a “racist”. And rube-Rubin calls their neo-Luddite behaviour by the name “context” which he adds.

You can’t take any of the “ad hominem”, or the “rube”, or the “rub”, out of Rubin…

Kevin

This was all foreshadowed over a decade ago in Napoleon Chagnon’s “Noble Savages.”

Right you are: “Noble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes — the Yanomamö and the Anthropologists” [Napoleon Chagnon; 2013]. Great title. Interesting anthropoid animal.

A friend of mine attended and presented at one of these conferences years ago. It was in a fun location, so I attended with her to see her speak and snuck into a couple other sessions. I’m not an anthropology student or scholar, but I have several college degrees, so the language of academia isn’t new to me.

I was aghast. I couldn’t believe how awful the presentations were – from the gobbledigook language to the anthropologist as subject of study, it was appalling how bad it all was. I remember a session where the guy had studied abroad in some middle east country. He spent his time hanging out on the front steps of the mosque people watching. He wrote about that experience and how it made him feel and that was sufficient to win a presentation slot. My friend gave an awful presentation too. Some of the presentations were so full of academia-speak that it felt like I was the victim of one of those hoaxes where some conniving students submit a nonsense paper to an academic journal and the journal publishes it.

I was recently looking up some of the classmates I’d gone to college with to see what they’re up to. A couple of them had kept blogs where they detailed their graduate school and beyond. I was struck at how totally lame their Masters and PhD thesis work seemed to be. To be fair, I haven’t read them. But one of them had spent years abroad studying for a PhD. His topic? His perspective on the healthcare system in the country he lived in. Is your personal perspective on a topic really PhD-quality research? Our educational system, from the bottom to the top, needs a major overhaul.

In the third quarter of 1964, I first began to read about “multiculturalism” and its supposed fight for cultures outside industrial culture, which just happened to be almost all agrarian cultures. I guessed then, that what it was had to be an assault on Industrial culture, because it was the *only* culture not defended. It was in journals of Social Anthropology I was reading this.

30 years later, I was trying to find out about the Schöningen Javelins, and finding Anthropology people unwilling to talk about their use, … and were obviously afraid for their careers. They didn’t want me bringing up the subject. 30 years on again, and we have this attitude that Professor Weiss finds, and the conclusion she correctly derives is that anthropology, as a scientific field, … is dead. It was killed by the reality of what “multiculturalism” is, over the last 6 decades, by the political reality of “multiculturalism”.

For universities, Science, is a newcomer. In universities, politics is *old*. Universities were first chartered (1088A.D.), for political reasons. Those political reasons are now stomping out Science, so that doing science at all must be apologized for, in the closest point of infection, in anthropology. That is spreading to other sciences as we read this, and to technology. 3 years ago, the Dean of Engineering at Purdue published a screed on how *rigor*, in engineering, is patriarchal, and must be set aside!

Science started outside the Universities. Acceptance by them only really came from 1800 onward. That acceptance is ending. Politics must again rule, or universities *will*not* be either chartered, or funded.

We need refugia for Sciences, outside universities. It is long past time to begin building them. The assault on industrial culture inside industrial society builds daily. Tolerance, for Science inside a political institution like universities, is ending. Industrial culture, and the industrial society that sustains it, will need somewhere else for Science to succeed.

Its really great to see the fruition of academic leftism. Keep up the good work!

In the early 1970s I became fascinated with Rodney Needham’s resurrection of A. M. Hocart’s seminal Kings and Councilors. Hocart’s approach to anthropology was historical and comparative, like historical linguistics. It had already long been supplanted in the UK by ‘functional’ social anthropology, more recently by the ‘structuralism’ of Levi-Strauss, and in the USA by what sounded increasingly like sophomoric (and ethnocentric) sociology. Unsurprisingly, it has all devolved into what Professor Weiss here describes as “inane research devoid of meaning.”

At one time, the various arms of anthropology were concerned with trying to understand the nature and history of different cultures, societies, languages, and their histories, “the study of man (embracing woman),” as we used to jest. It was oriented to uncovering facts, and attempting to understand them using the scientific method. Now apparently these aims have gone completely by the board, and the only aim seems to be writing exercises in validating extreme left-wing ideology and slogans, which, having no referents in reality, are truly “devoid of meaning.”

I am thankful that I got out of the field when I did.

I’m just a simple observer, but I’ve known, employed, and worked alongside and for Pueblo and Tribal members in New Mexico for years. For me, the money quote was how the Nuxalt are “constantly reinterpreting” what is sacred. Why does today’s anthropologist discount the idea that the are being played? Today’s members are not some ethereal beings floating along on an elevated astral plane. They have their own historic hatreds, rivalries, affections, and animosities. They are as good and as bad as any Anglo or Spanish descendant and they are not above milking academics and politicians. They know how to leverage today’s zeitgeist for their own benefit. Everyone massages their reality to suit themselves and the image they want to project. An anthropologist, no less than a lawyer, should treat any representation with skepticism. It appears skepticism has been bred out of the academic herd.

Very depressing. 😔

EVERY discipline in the sciences has been hopelessly corrupted by the insane. Even math is racist. Physics has to be replaced with “indigenous” mysticism. This is how western democracies are being destroyed. By foreign-sponsored kookery that censores and censures any and all who object to the bastardization of ACTUAL SCIENCE.

And where are people with a smattering of common sense that will lift their eyes and repeat the refrain “bullsh*t”? Because that is all it deserves.A fantastic match back to stupidity, because that is what it is. By people with alphabet soup after their names who are too cowardly to call a spade a spade. Cast of your chains. Look someone in the face and just say “Bullsh*t”. Laugh at them. Point fingers. It will work.

It you reply “bullsh*t”, then you’re out of the field. You don’t get your degree, you fail your course.

Burn it down, salt the fields and start again, that’s the only way that this gets fixed.

I took a general anthropology class pass/fail at a prestigious ivy league university in the early 1970s. the class was “taught” by 2 anthropology graduate students who were already, even back then, so tongue-tied by wokeness before it had a name that it was totally worthless to attend class sessions. I blew the course off but did not withdraw. As a biology major, I submitted a required paper about whether bee language blurred the line between humans and animals, and (frankly to my surprise) received a Pass grade.

Thanks very much for this first-hand report. I had heard rumors that the discipline of anthropology had killed itself. Your report, unfortunately, proves those rumors right.

I earned a Bachelor’s degree in anthropology in 1980. I had decided I didn’t want to teach and couldn’t find a job in the field, so I studied engineering. Even after entering a very different field, I continued reading anthropology books and articles, because they were so fascinating. At their best, anthropology texts were interesting, affecting, and literate. We started with Colin Turnbull’s _The Forest People_. It was a passionate defense of the pygmies of central Africa. Not only was it interesting, but by turns also funny, entertaining, and infuriating. Buck Schieffelin’s _The Sorrow of the Lonely and the Burning of the Dancers_ was likewise a fascinating and sad book. One could go on. There were so many stories to tell and so many gifted writers among anthropologists. I’m sure present-day anthropologists have reasons no one tells such fascinating stories with such literary flair any more. Sad.

Science is being replaced by subjective and trendy interests. The problem is that any “science” group that behaves like this vapid group of archeologists are immediately exposed as having to little critical-thinking ability … and hence the whole field is now questionable as to its worth.

“It seems as if anthropology lies in ruins. Much has gone into the demolition work, including talks about oneself, an avoidance of traditional scientific methods, a lack of imagery, a preoccupation with current political fads, and a self-hatred of the field’s history.”

Professor Weiss sums up well the state of anthropology. Vandals who can do nothing constructive choose to destroy. The rich field of anthropology, in which I worked for over fifty years, was a splendid achievement of many dedicated minds. Now there is little to nothing being done of value.

I’m a retired physician and ,unfortunately, this same type of inane , stupid attitudes and

practices have crept into medical education and to some degree professional associations. At least when it comes to academics ,departments like anthropology will more or less go down the tubes like History, English, Sociology, when this type of education is seen as useless and actual jobs are few ( those PhD presentors better think hard about their future- only so many jobs for boobs).

I have just retired from an active anthropological career as a professor and a dean. And I must confess that today’s AAA programming reads foreign to me. I have long criticized the MLA because of their ‘jargon-ridden’ paper titles and making nouns into verbs and vice versa, and I am disappointed that the AAA has fallen into that trap BECAUSE it hides the arguments being made and therefore discussion that can follow. All that being said, I have a couple of comments.

First, my field of European Archaeology, specifically the post glacial (and first) settlement of Ireland, is still immersed in a colonial narrative of ‘white’ settlement’ and indigenous passivity. More than that, the 1920’s Eugenics movement is still in the fabric of theory that underlies invasion hypotheses and aboriginal inferiority. So de-colonizing Anthropology,(which is after all the daughter of Imperialism as Kathleen Gough so clearly demonstrated decades ago) needs to be self-criticized.

Second, with regard to the relevance of Anthropology: the divide between so called Woke and “Heterodox” Anthropologists is a distraction set up by the political and powers that be

to keep academics fighting among themselves and from trying to deal with the obscene inequities of our society and the world in general. There are so many practical matters to be dealt with (for example student debt) it is a pity that we fight over masks, fist bumps

and sensitivity indicators.

So, youre the PROBLEM. Destroying Western Liberal Society in one generation was a feat only a truly useful idiot Marxist could accomplish. You should be embarrased at your distasterous career. Future anthropoligists will use the Marxist Histories of academics like you as a case study in anti science anti human ideology of Progressive Commie/Fascism in the early 21st century.

Woke is simply another new flavor of European administrative police state Fascism. A real far right wing etremist named George Washington was shooting Redcoats because of an over-priced stamp. What do you think he would do to you big Govt anti Americans?

No. Wrong. You’re definitely part of the problem. Anthropology has been a joke since at least the 90s, when everything was Foucault this and deconstruct that.. The fad chasing bootlickers of academia have simply moved to the next cliched vapidness. Interrogating whiteness and recentering colonialism or whatever this week’s Twitter phraseology is simply shows that anthropology as done by the full-employment-for-left-wing-morons crowd is not a real disciple and should not receive any funding whatsoever. A waste of taxpayer money taken from decent people and given to inbred dilettantes circle jerking their queerologies. As to the second point, that anyone gives two craps about what anthropologists do or think, grow up. Once you retire and actually mature and take on responsibility, you might become a human, instead of an academic.

Prof. Green’s interesting post deserves much better than the couple of conversation-ending maga-type jeremiads that followed. Describing ancient or prehistoric human migrations as “invasions” has often been misleading, as in the case of Anglo-Saxon migrations to eastern parts of Britain during in the wake of the Romans’ departure. Open-minded and evidence-based archaeological investigatiors of gravesites and village sites from around 1500 years ago have revealed much intermingling and interbreeding between Anglo-Saxons and Britons and very little evidence of combat-type injuries to skeletons dating from that era. Actual evidence from the DNA in human remains, skeletal remains, and other archaeological evidence suggests that the lurid accounts of violent and murderous Anglo-Saxon “invasions” by Bede and other medieval scribes are simply inaccurate and have been been uncritically accepted at face value by much of the general public.

“In her talk on missing and deceased people in Mexico, Marina Alamo Bryan, a PhD student at Columbia University, gave some startling statistics: since 2006, 100,000 people have gone missing in Mexico…. Bryan showed us three sonographs: one from a rooster’s crow at a mass grave site, one from the sound of protestors, and one of onions frying at the church where searchers gather.”

I would have asked how those were related to what clearly is mass murder — or is one no longer allowed to question presenters?

As an aside, I don’t believe this 100,000 figure includes those people who have simply been found dead in Mexico — Mexico has been quite violent for over a decade now with heavily-armed cartels shooting anyone who gets in their way. From what I understand, mass shootings are fairly common in that country now….