From a bird’s eye view, most children stories can be understood as a process that guides the child into becoming a member of society──a member of a particular culture, a particular place, and a particular time. We tell them about dangers, morals, customs, and cultural beliefs, and how to perform the rituals of daily life. My favorite is Ayaan Hirsi Ali recounting the names in her lineage as she sat under the talal tree with her grandmother.

The names will make you strong. They are your bloodline. If you honor them they will keep you alive. If you dishonor them you will be forsaken. You will be nothing. You will lead a wretched life and die alone. Do it again. (Infidel, Bloodlines, p. 3)

Such stories can be more than fables, legends, heroic tales, or, these days, tales of grievance that aim to mold anger toward an evil other.

If the storyteller is also a culture warrior, the stories may seek to impose different values about gender, sex, race, parenting, and history. The storyteller may enter into a struggle about facts and “truth” claims, and may participate in the debate about education becoming indoctrination. This is a recurrent phenomenon when one cultural milieu grinds against another. In the early 1950s, I was forced to toss several dozen EC comics into our building’s incinerator out a fear my mother had. A Comics Code became essential and required:

A crackdown on “sexy” images . . . criminals should always be bad and never triumph over good . . . authority figures . . . should be respected; a ban on torture; werewolves, zombies, vampires, and ghouls couldn’t be used; entreaties against slang and “vulgar” language.

There are separate issues about pedagogy—banking knowledge versus an action and process method. If you think this reminds you of Pink Floyd’s popular song “We don’t need no education,” you are in the right room.

Children’s literature moves the discussion into a relevant and effective teaching style, with one eye on classroom management, another on materials, and a third on whether students are paying attention.

Given this complexity and layering of perspectives, I selected one issue that seems to be at the apex──whether the story’s content is “telling the truth.”

Rebeldita and Christopher the Ogre Cologre

Oriel María Siu is the author of a children’s book series about a “happy, fearless girl of Indigenous and African descent,” Rebeldita the Fearless. Siu echoes the name of Dr. Seuss and his children’s book series with her own credentials as Dr. Siu. Her escape to Los Angeles from Honduras under threat from the MS-13 gang is, in her own words, ironic, since it lands her where many of her demons reside. Her lived irony continues as she writes from both Los Angeles, California and her hometown, San Pedro Sula, Honduras.

When speaking of the history of Christopher Columbus and the European conquest of her homeland, we find that her “homeland” resides within a complex personal story. She is the child of a Pipil Salvadoran/Guatemalan mother and a Nicaraguan Chinese father. Her personal narrative is reframed in Rebeldita’s character of indigenous and African descent. At the core of both personas is a Manichean struggle of victims against oppressors.

Siu’s first book engages Rebeldita in the recent Central American immigration crisis, reflecting the desire of many migrants who seek to enter the United States. Here we find a contemporary transnational land of ogres. Alicia Siu, the illustrator for this book and sister of Dr. Siu, explains the face of these modern ogres: “They’re dictators, they’re narco cartels, they’re elite families and extractivist companies.” Dr. Siu herself notes other modern ogres: Wallogro Street, Ogrump Tower, Coca-Cogra, Hollogrywood, Fondo Monetogro Internacional (IMF).

Her second book looks to the history of her imagined America before it was America and to what it has become: the United States. As she explained in a Los Angeles Times profile: “It’s at the core of what the United States is”—slavery, colonization, and Christopher Cologre (Christopher Columbus as an ogre)—“the first Ogre to come to the Americas.”

Caveat

I would be remiss in talking about cultural stories to frame a narrative—such as Dr. Siu’s—without mentioning one that I embrace each year. Such narratives are useful to give meaning and an identity for a group’s coherence. My own narrative is the Exodus, repeated each year at Passover. The narrative is set forth in the Hebrew Bible and the haggadah (a telling), and it focuses on a new and angry pharaoh who feared the growing number of Hebrews living in Egypt. The story transmits a cultural narrative that has been told for thousands of years. The story is told to four sons: a wise son, a wicked son, an ignorant son, and one who is unable to formulate a question. These four sons have different abilities to learn, and they show how an ‘answer’ needs to be framed for each one. This is an appropriate scaling to how one learns a cultural narrative.

[Related: “The Pipeline of Indoctrination”]

What is forgotten in this narrative of liberation is an earlier historical moment. A far smaller group, the extended family of the Patriarch Jacob, traveled to Egypt during a famine in Canaan. The pharaoh at that time had been enamored of the work that Joseph performed and granted these Hebrews favored land in Goshen. It was only after hundreds of years that a new and fearful pharaoh arrived, oppressing the much larger population of Hebrews.

At a very abstract level, Dr. Siu’s Rebeldita (together with her abuelita/grandmother) is analogous to the rebel Moses. Both are seeking liberation, a freedom from the ogres of their respective historical contexts.

Does it matter that such an exodus may not have happened or may have differed from the biblical narrative? For literalists and archaeologists, an answer may be compelling. For today’s Jews, the narrative continues to provide meaning about cultural identity. For gentiles, the freedom metaphor provides motivation: the Pilgrims saw themselves crossing the Red Sea (the Atlantic Ocean) and escaping the Pharaoh (King James I); for slaves in early America, the Exodus metaphor was about freedom and gave voice to hope in Go Down Moses. That provided a reason for slave owners to ban this song. Even the caravans of Central Americans seeking to cross into the United States through the southern border (2018-2019) preferred the Exodus metaphor to the eagle and condor that was favored in the Standing Rock protests in North Dakota.

In the sense of metaphor, Moses and Rebeldita symbolize liberation. The stories are related to children as part of their inculcation into their respective communities. Moses is the hero against the Pharaoh of his generation; Rebeldita is the heroine against the myth of the Cologre found in many textbooks over the course of generations.

But the general analogy begins to fall apart as we descend into context. Particularity matters, the more so when we move beyond the metaphor and makes claims about telling the truth. A children’s story that requires historical accuracy, something more than a myth, requires a thorough portrayal of historical circumstances and pedagogical fairness. The story of the Exodus does not need to be accurate to motivate a quest for freedom. By contrast, the story of Rebeldita seeks to undo traditional conceptions of identity in the United States.

Pedagogical Fairness and Standpoint Epistemology

How should we refer to the continents of North America and South America?

From the standpoint or perspective of European colonization, we refer to the combined area as the Americas. However, from the perspective of the Guna language, this area is Abya Yala; that view was adapted by the Bolivian Aymara leader, Takir Mamani, who stated that “placing foreign names on our villages, our cities, and our continents is equivalent to subjecting our identity to the will of our invaders and their heirs.”

Semantics place the cultures that inhabit this land mass in an antagonistic epistemology. Seemingly, it affects the truth value of statements such as:

We are a nation of immigrants.

Columbus discovered America.

These statements, familiar in the United States, are accepted as a generally accurate description of reality. It is also the way in which most inhabitants view this nation. From a European perspective, Columbus was credited with discovering America despite Leif Erickson, who likely arrived hundreds of years earlier, and the contributions of others such as Amerigo Vespucci, for whom the continents are named. The “discovery of America” is understood as a contingent truth, given the perspective of indigenous inhabitants who were already here.

However, Dr. Siu adopts the metric of Abya Yala, the awareness of pre-Columbus inhabitants. Rebeldita concludes her story by declaring, “Go free Abya Yala from ogre lies no matter what their tricky disguise.” In effect, if it is true that Abya Yala inhabitants were already here, then according to Dr. Siu, Columbus’ “discovery” must be a lie. But is a different awareness a lie or a truth? Or simply different referents for different contexts?

How should we understand the dilemma in which the statements that “We are a nation of immigrants” and that “Columbus discovered America” are both true and false (or a contingent truth), depending on one’s standpoint.

The Teaching Guide that accompanies the Rebeldita books illustrates what pedagogical fairness does not mean. Rebeldita’s pedagogy requires rejecting a lie (America) and accepting a truth (Abya Yala)—here is no room for discussing differing perspectives. The complete title of the guide is: “Teaching Guide for Educators Teaching the Truth about Christopher Columbus, White Settler Colonialism and History of the Americas from the Perspective of Indigenous and Black Resistances.”

[Related: “When Ethnic Studies Education Violates the Law: California’s Guardrails”]

So, historical truth──the capital-T Truth──is the “perspective of indigenous and black resistances.” To be sure, this is not the truth for all indigenous peoples, nor for all black Americans; this truth also excludes Asians, Europeans, and Latinos. How useful is it to tell impressionable young children that this is the Truth, as opposed to different viewpoints, about the peoples of this land?

Siu argues for her perspective as the Truth: “We need to rewrite these transnational foundational lies because it makes a huge difference in how children and young adults later on conceive of themselves and their world.”

As adults, we are able to recognize such arguments as the pot calling the kettle black, but for children 4-8 years old—the age for which the Rebeldita book is appropriate—converting an argument over contingent truths into one about absolute truths likely undermines a stable understanding of reality. Siu acknowledged in a public forum that it is only parents and teachers who complain about her approach, and never the children to whom she reads these books.

The Truth about Ogres . . . and Humanity

In none of the Rebeldita books are there pre-Columbian ogres. There is no mention of settler colonialism in pre-Columbian imperial nations nor any mention of pre-Columbian warfare or human sacrifice. A quick Google search would reveal the same zeal for ogreness in Abya Yala.

• Although the Maya were never a unified empire like the Incas or Aztecs, the city-states nevertheless had much contact. . . . Warfare was also common: skirmishes to enslave people and take victims for sacrifice were common, and all-out wars not unheard of.

• Religion permeated every aspect of Aztec life, no matter what one’s station, from the highest born emperor to the lowliest slave. The Aztecs worshipped hundreds of deities and honored them all in a variety of rituals and ceremonies, some featuring human sacrifice. In the Aztec creation myths, all the gods had sacrificed themselves repeatedly to bring the world and humans into being. Thus, human sacrifice and blood offerings were necessary to pay the gods their due and to keep the natural world in balance.

• [Pachacutec] was joined in battle by his warrior son, Túpac Yupanqui, who later became the tenth Inca, from 1471 – 1493, and continued his father’s expansionist traditions. During his tenure, the Inca Empire grew to cover the territory from northern Ecuador to northern Chile and Bolivia, and from the Pacific coast into the Amazon lowlands. The Inca had taken barely half a century to grow into the greatest empire of the New World.

If Dr. Siu wanted to “tell the truth,” however uncomfortable, Rebeldita (or her abuelita) would have been more sanguine about Abya Yala’s history (see Figure 1). The complete history of the continent would not excuse the brutality and imperialism of European conquest. What it would show is the way in which humanity has developed across the world; it would also show the connectedness between Abya Yala and America—a realism about power, governance, and grief, and an opportunity to seek a more humane model. Moreover, a complete history would not focus on the malevolent aspects of humanity, whether particularized as European or indigenous, but would allow for cultures to be seen in a well-rounded way.

The Teaching Guide for Christopher the Ogre Cologre advocates for “speaking truth to children” even if it is considered “difficult” and “uncomfortable,” or if the children might be “too young to understand.” Thus, telling about pre-Columbian ogres would be both acceptable and critical to “truth telling.” However, education can become indoctrination when a one-sided point of view is reworked as “truth telling” and then truncates a more complete set of facts to fit an agenda: the Teaching Guide’s agenda is explicitly stated as one of “dismantl[ing] the dangerous lies and myths taught in schools about Christopher Columbus and white settler colonialism.”

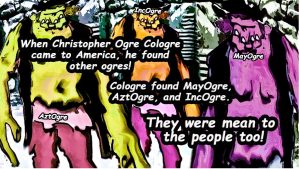

Figure 1: Reimagining Ogres. A pre-Columbus perspective would include Aztec, Mayan, Incan, and other imperial civilizations that were settler colonialists.

A Reflection and an Invitation to Dialogue

Many thousands of migrants from Central America have journeyed the United States in recent years. The decision to make this perilous journey is framed as escaping violent gang activity in their homeland and economic opportunity in the United States. For Oriel María Siu, her decision to leave Honduras for the United States was ironic, given the myths she uses in her children’s books, such as America being a land of immigrants. Now multiply that irony a thousand-fold for her compatriots that made the same journey──from Abya Yala to America. Except, I would imagine, that her fellow Hondurans did not undertake the journey from the perspective of an ideological irony, but simply a pragmatic realism.

[Related: “Ethnic Studies and DEI—A Convenient Marriage Anchored in Critical Race Theory”]

So, how should we understand that difference in Siu and her compatriots’ consciousness?

This is the classic problem for some social theorists. The thousands of migrants are making individual choices, “produc[ing] a view of oneself as a single entity engaged in competition with others of one’s social and economic standing, rather than as part of a group with unified experiences, struggles, and interests. According to Marx and other social theorists who followed, [individual or false] consciousness was dangerous because it encouraged people to think and act in ways that were counterintuitive to their [class] economic, social, and political self-interests.”

Siu’s problem, with respect to her fellow Central Americans, is similar. She commands the “true” history and the “true” understanding of Abya Yala while her compatriots are stuck in their individual and “false” consciousness of survival, leaving their homes to come to America, the land descended from Christopher the Ogre Cologre.

I had the opportunity to ask Dr. Siu about a wider historical perspective (LESMC presentation, June 11, 2022). Her response focused on her concern about the “apologetics” of a Eurocentric view in K-12 curriculum.

Dr. Siu: Let us dialogue to a better place—to a promised land that can embrace all Abya Yalans and Americans.

Righting the history of the Americas is a worthy enterprise. However, that objective can become blurred and divisive in a history truncated by a racialized agenda.

Gotta love an immigrant with no self awareness. She comes to the US and calls herself indigenous which would imply she’s indigenous to this part of the world and not from another boundary. This irks me, I’m indigenous, Iroquois and she and others like her are worse that any colonizer from hundreds of years ago. She is colonizing my country now but unlike the settlers, she has come to a developed nation because she couldn’t get what she needed at home. She’s acting very disrespectful of to the citizens of the US by insulting us and thinking it’s her duty to alter things to meet her demands for recognition she doesn’t deserve. She’s pushing her beliefs and her rules on our kids, much like the hated colonists did. But she’s not bringing anything constructive to the table. Yeah, she offends me to no end. Someone should remind her that she’s a colonizer. Nobody likes a disrespectful and ungrateful foreigner.

Several issues came to mind in discussing “truth” in children’s literature. Towards the end of the article, there is an assumption that it is important, to tell the truth to children, no matter how difficult. As an educator, it was always my feeling that children have the best minds since they are the freest and don’t have stereotypes of dogma on which to rely. Just any five-year-old who is verbal and you will get a great story. As the child gets older he/she makes the assumption, what is this that the teacher/adult wants to hear.

If we want to impart “truth” to children, it is necessary to determine what is appropriate and how to present it. The Haggadah is a wonderful example in that there are so many versions necessary to appeal to people of varying cultures and origins. Furthermore, what is “true” to one person may be entirely different to another.

I recall a cute story: Five-year-old David asks his mother, “Where did I come from? His mother contemplates, then goes into what she considers an explanation about the birds and the bees. After this discussion, David says, “Robbie comes from Ohio. So where did I come from.”

Admittedly I read through this just once and took a few notes. Perhaps, if I read it again more things will ‘pop’ out.

Good catch. Yes, the illustrations are very telling. Even as an adult, they spoke to me with more immediate impact than the story itself.

My brief memories of being 5 years old make me think these children who “Don’t object” to the book, are just glad not to be in class learning the alphabet and math. Storytime was always a fun time – the book itself was never that important. HECK, we couldn’t even really SEE the book unless we were on the front row of the carpet!

It’s interesting to see the aesthetic of this book; I also googled some other images. The aggressive crudity and ugliness of the art in a work directed at children is very telling.

It would have been possible to pair the story (agree or disagree with it) with art work that was beautiful, with the heroine and her friends rendered in a way that invites imaginative rumination, and the ogres done the way Arthur Rackham did pirates or gnomes.

This sort of faux-naive “populist” style,in a book produced in concert with a very slick marketing campaign, is such a kind of immediate indicator of bad faith. You see it a lot in the contemporary astroturfed left.

Interesting and well written. Yes standpoint USA key. Especially because “what you know is what you see”. So children are educated in within their culture-historical context, but need to know all the “truths” you note.

The status quo can be yesterday’s radical agenda.