As we live through our current “Woke” Revolution, it is helpful to reflect on what we can learn from past revolutions and revolutionaries.

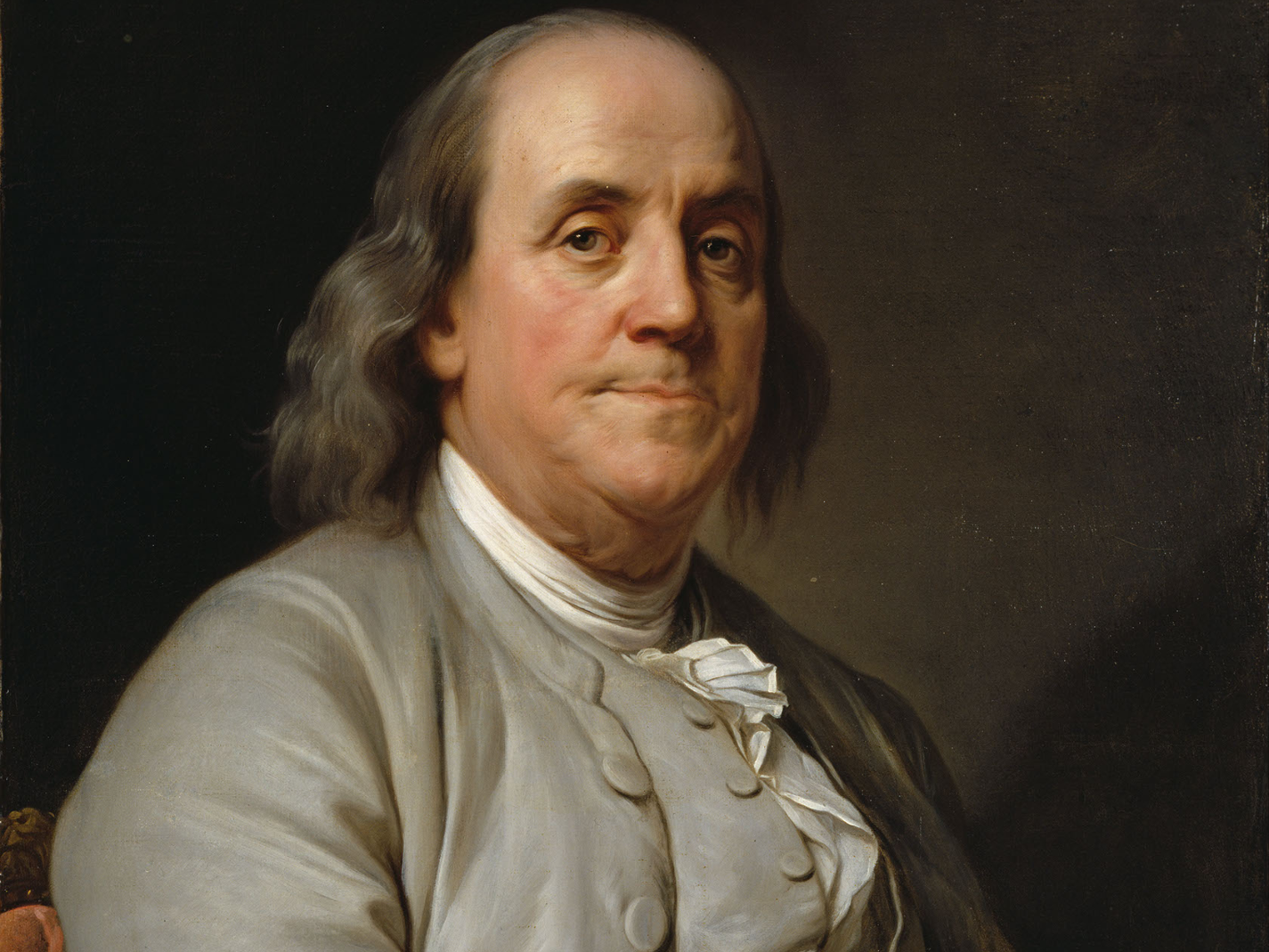

Long before he was a Founding Father, Ben Franklin was one of the most successful “influencers” (as we’d say now) in the American colonies. His Poor Richard’s Almanack was a multi-decade bestseller. In 1758 he summarized a quarter-century of Poor Dick’s wisdom in The Way to Wealth—a book that gave birth to the “self-help” genre and that remains in print today.

Given such popularity, it’s no surprise that The Way to Wealth looks thoroughly conventional. In it, Poor Richard purports to relate a “sermon” he heard given by a white-haired village elder, Father Abraham, to an crowd waiting for a sale. In quintessential American fashion, the crowd complains to Abraham about taxes. In response, Abraham denounces what he calls the far heavier taxes of idleness, pride, and folly. To combat these vices, he extols four virtues: Industry, Care, Frugality, and Knowledge.

These virtues would remain instantly recognizable to generations of Americans. Industry is “doing to the purpose,” creating property through labor. It is the engine of progress: “Early to bed, and early to rise …” Care does not mean helping others but rather “attention to one’s own business”; it supplies Industry’s purpose. Abraham spends the most time on Frugality, which means saying No to one’s desires, especially prideful desires for fancy clothes, food, drink, and entertainment. He deals briefly with Knowledge, which experience offers even to fools, teaching the means to attaining one’s industrious ends.

Under the effects of our current Revolution, these virtues long ago started to lose their shine. Today we’re taught to equate work with “passion” and “dreams.” In such light, Industry looks like drudgery or mere money-grubbing. Care sounds like rigidity, narrow-minded doggedness, “mini-mind” thinking “inside the box.” Rather than Frugality, people have long since learned to embrace debt: isn’t it what allows us to consume more stuff? Isn’t the Consumer is the key to the nation’s economy and hence to its political future? Debt-fueled consumption is practically a public service!

Knowledge may be a somewhat different case. Our wise men (and women) hold almost universally that “knowledge” about right and wrong and virtue and vice is impossible. Many even say that all knowledge and science are mere claims of power over other people. But not all do, yet. Some people still hold a respect for science, for the claim that there is objective truth; that there are things to know and that we can know them; and that this knowledge even extends to making our lives better.

The esteem for Knowledge, tenuous as it is today, remains one thread that still connects us with Franklin. Perhaps it is also a reason why Franklin seems relatively unscathed by the imposition of the Woke faith on our public education and public spaces.

However, the apparent conventionality of The Way to Wealth should not deceive us: it was and remains a revolutionary book.

Franklin’s clever choice of frame is a tip off. Though Poor Dick calls this speech a sermon, it is by no minister. “Father Abraham” recalls the patriarch of the Bible, the founder of the people of Israel. But that Abraham, as a founder, abandoned the gods of his fathers. Most strikingly, Father Abraham in his sermon does not take as his text the Holy Bible. Instead, as Richard listens, Abraham quotes … Richard! Father Abraham’s Bible is none other than Poor Richard’s Almanack. (Which makes Richard’s creator, old Ben, none other than God.) Father Abraham barely mentions the Lord in this “sermon.” We’re hardly surprised, then, by the point of his speech (to paraphrase): “Lay up your treasure in this world!” This is certainly no Sermon on the Mount.

(The few places Abraham references God or faith underscore Franklin’s unorthodoxy: “God helps them who help themselves.” “God gives all things to Industry.” “.. he who lives upon hope will die fasting.” “In the affairs of this world, men are saved not by faith but by the want of it.”)

Likewise, Franklin’s choice of four virtues is no accident. They slyly replace the four cardinal virtues that guided Western civilization for over two millennia. Industry resembles Courage; both are striving and full of effort. But whereas the courageous man endures pains for the sake of the noble, sometimes even sacrificing his life, the industrious man labors for the sake of property, thereby protecting his life. Care sounds like the Justice of the Republic, which Socrates famously defined as “minding one’s own things.” But by “one’s own things” Socrates meant doing one’s part for the common good, not Richard’s “Serve yourself.” Frugality and Moderation both manage desire. But the frugal man “suppresses” his desires; the moderate man desires only the right things. And Knowledge replaces Prudence. As noted, experience offers Knowledge even to fools, while Prudence, the knowledge of the human good and how to achieve it, is a rare virtue that belongs above all to statesmen.

The net result is that The Way to Wealth lowers the bar for virtue, democratizing it, and making it accessible even to the crowd. To do so requires largely jettisoning nobility and right. Franklin thereby greatly simplifies the moral life. There’s little need here for a long process of formation, habituation, or education. The life described by Father Abraham is remarkably uniform from beginning to end. As he quotes Richard, “For age’s want, save while you may / No morning sun lasts a whole day.” Or, “Get what you can, and what you get hold.” In contrast, “A fat kitchen maketh a lean will.”

In sum, the man who lives according to Poor Richard’s wisdom, as distilled by Father Abraham, hails neither from Jerusalem nor from Athens. He is a new man—a modern man. Franklin beheld, and helped shape, a Revolution.

Franklin’s The Way to Wealth, then, is a book neither to reject nor to regret but to learn from; it offers several lessons of prudent writing and thinking for our troubled times.

First, Franklin is not Poor Richard, much less Father Abraham. Franklin himself was no enemy of debt. He was an entrepreneur, a philanthropist, and a darling of the Paris salons—activities that would seem suspect to the humble Richard. Franklin thus shows that one can shape a Revolution without being of it. He encouraged certain low but solid aspects of modern man to deter certain even lower ones. All the while he preserved a place for science, not just the “latest thing” but “the sense of all ages and nations.”

Second, every Revolution seeks to impose its image of the “New Man” upon the true diversity of humankind. Franklin and his creations remind us that there are many different types of men. This is a comforting reminder in the face of the smug conformity of the Woke.

Third, Franklin’s book underscores what we are in danger of losing as the American Revolution is superseded. Since 1758 many critics have snorted at Franklin’s “shopkeeper morality.” What is admirable in The Way to Wealth? It is the image Father Abraham offers in his words on Frugality: “A plowman on his legs is higher than an aristocrat on his knees.” Covered in muck and mire, a plowman cuts no fine figure. But he’s hard-working and careful. By not being led by Pride into debt, he gives no one else power over his liberty. He bows before no master. Indeed, as Abraham’s reference to the aristocrat reveals, bowing occurs not only to creditors but also to a liege, a lord, a king. This plowman is politically independent. And, from hints we’ve already noticed, the American plowman’s independence could even include not bowing to God.

By encouraging readers to stand on their own two legs, to provide for themselves, and to see the world for themselves, Franklin’s first three virtues allow his new man to live without shame and without lies. They also provide the conditions for his science or Knowledge. This is a point we could do well to hold onto, in a time in which a bureaucrat can unironically claim, “I am the Science.” The Way to Wealth points to more than money: besides a longer and healthier life, it promises a life that is honest, unashamed, upright, self-sufficient, and, in a word, free. Not a bad result from a Revolution—if we can keep it.

How does this fit in?

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/anxiousbench/2015/12/ben-franklin-anti-catholicism-and-the-founding-of-the-university-of-pennsylvania/

Correction to my previous comment—it was written in Amsterdam after he left Italy. In addition to religious/ethical/mystical books, the author also wrote poems, plays, and works on logic.

This, written in Italy in the 1700s, is much more valuable as a guide to the true virtues:

https://www.amazon.com/Path-Just-Moshe-Chayim-Luzzatto/dp/1583306919

People tend to forget that Franklin ran away from an apprenticeship in Boston.

Indeed, on his own two legs.

Brilliant:)