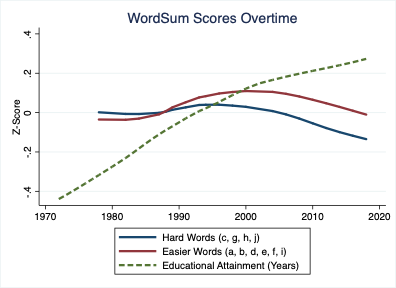

People’s vocabularies are shrinking at a time when more and more people have college degrees. As Zach Goldberg notes, people’s mastery of hard words has been falling for well over 20 years, and their mastery of easier words has been falling for over 15 years. Meanwhile, a higher proportion of Americans have college degrees than in the past, and their average amount of education in years has grown. These trends are illustrated on his graph, “WordSum Scores Overtime, below

Going to college no longer expands people’s vocabularies the way it once did: since 1970, there has been a steady decline in the correlation between years of education and people’s vocabulary.

Nearly half of the nation’s undergraduates learn almost nothing in their first two years in college, according to a 2011 study by NYU’s Richard Arum and others. Thirty-six percent learned little even by graduation. Although federal higher-education spending has mushroomed in recent years, students “spent 50% less time studying compared with students a few decades ago.” The National Assessment of Adult Literacy also shows that degree holders are learning less.

People’s minds may not expand much from attending college, but their indebtedness sure does. Increased college attendance has resulted in an explosion in student loan debt. Student loan debt now exceeds $1.56 trillion, saddling 45 million Americans with indebtedness averaging around $35,000 each.

The federal government provides more student loans and spends more money on higher education than it used to, but colleges just raise tuition to match the increased spending. That’s the conclusion to be drawn from a 2015 report by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York: “On average, the report finds, each additional dollar in government financial aid translated to a tuition hike of about 65 cents. That indicates that the biggest direct beneficiaries of federal aid are schools, rather than the students hoping to attend them.”

By subsidizing college, federal financial aid diverts young people away from vocational training that costs taxpayers far less but can lead to jobs with better pay and more value for America’s economy. In City Journal, Joel Kotkin described the rising pay and opportunities for workers in manufacturing, who often need vocational training rather than college educations.

Yet, states spend billions of dollars operating colleges that are little better than diploma mills in terms of academic rigor, yet manage to graduate few of their students—like Chicago State University, which had an 11% graduation rate in 2016. As one education expert noted, “Our colleges and universities are full to the brim with students who do not belong there, who are unprepared for college and uninterested in breaking a mental sweat.” Many drop out of college before acquiring a degree, but after running up student loan debt that will haunt them for years.

Education expert Richard Vedder sums up education’s decline over the last generation as “Spending Triples; Results Slide.” As he notes,

Spending on K-12 schools, adjusting for inflation and enrollment growth, has roughly tripled over the last 50 years. Yet there is little solid evidence that today’s students are better prepared for work and citizenship than their grandparents were — and even some evidence that they are less so. College costs are soaring, and almost certainly, the education system is becoming less efficient, at a time when labor productivity is rising elsewhere. More college grads are taking low-skilled jobs occupied previously by those with high school diplomas — more than 80,000 bartenders, for example, have at least a bachelor’s degree.

Colleges have spent much of the increased tuition they now charge students on vast armies of college bureaucrats and administrators. Professors have benefited far less. By 2011, there were already more college administrators than faculty at California State University. The University of California, which claimed to have cut administrative spending “to the bone,” was busy creating new positions for politically-correct bureaucrats even as it raised student fees and tuition to record levels. As the Manhattan Institute’s Heather Mac Donald noted in 2011:

The University of California at San Diego, for example, is creating a new full-time “vice chancellor for equity, diversity, and inclusion.” This position would augment UC San Diego’s already massive diversity apparatus, which includes the Chancellor’s Diversity Office, the associate vice chancellor for faculty equity, the assistant vice chancellor for diversity, the faculty equity advisors, the graduate diversity coordinators, the staff diversity liaison, the undergraduate student diversity liaison, the graduate student diversity liaison, the chief diversity officer, the director of development for diversity initiatives, the Office of Academic Diversity and Equal Opportunity, the Committee on Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Issues, the Committee on the Status of Women, the Campus Council on Climate, Culture and Inclusion, the Diversity Council, and the directors of the Cross-Cultural Center, the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Resource Center, and the Women’s Center.

Author Mark Bauerlein on these pages, a professor of English, decries corruption in his field. That fact contributes directly to poor vocabulary among new minted graduates. An essential function for English professors, in case you thought they had none, should be to further English vocabulary, I’ve an English degree, but also an Engineering degree; I needed to make a living. Vocabulary as well as mathematics disciplines ones mind.

Yes, and for a fun time, try using the word “asinine” or “niggardly” — legitimate words that have nuances of meaning that often make them the only appropriate word to use.