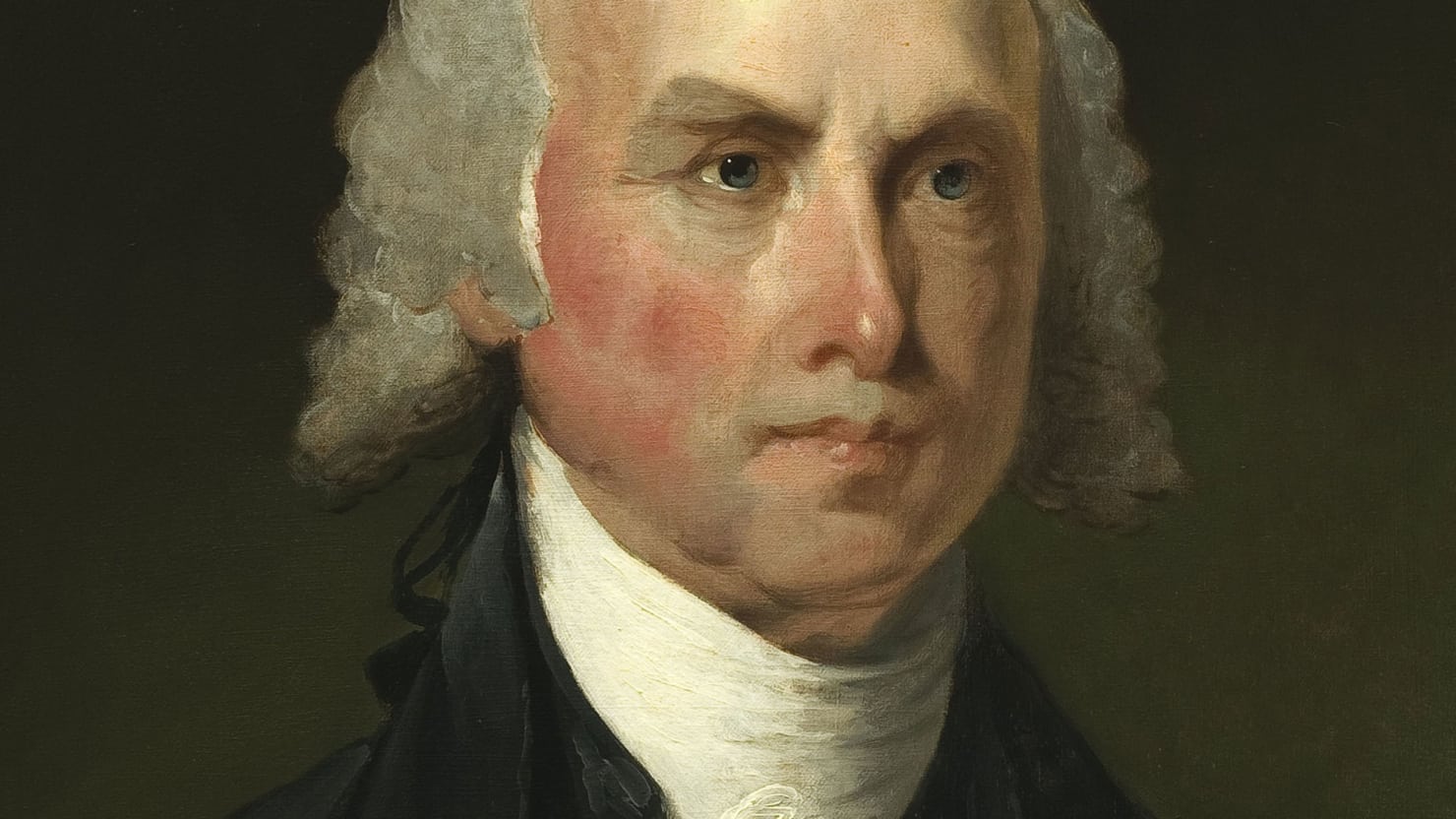

When I last visited Montpelier, the ancestral home of James Madison and his wife Dolley in northwestern Virginia, about twenty years ago, the principal exhibit focused on the ideals and ideas of the U. S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, and the contributions made to them by the man called the Father of the Constitution. To my surprise and dismay upon a return visit to Montpelier in May 2018, that exhibit had disappeared and had been replaced by one that tells the story of James Madison as a slaveholder, how slavery was rooted and protected in the Constitution, and how that legacy is manifested in America today.

The new Montpelier exhibit adds to the transmogrification of the public presentation of American history at our museums and historic sites, which the academic left (and their affiliated progressive and postmodern multicultural elites) has achieved. The ideologically refitted narrative presents the oppression of marginalized groups and injustice as the principal story of American history—replacing the understanding of our founding ideals and ideas, the applications of our governing principles, and the positive achievements of our nation’s past.

The Montpelier Exhibit

The new Montpelier exhibit is titled “The Mere Distinction of Color,” after remarks Madison made at the Constitutional Convention: “We have seen the mere distinction of color made in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised of man over man.” The exhibit was developed by The Montpelier Foundation and completed in 2017. An article in the National Trust for Historic Preservation by Carson Bear describes the new exhibit and its purposes:

James Madison’s life and legacy are deeply entwined with the lives of enslaved individuals; the ideas of freedom and liberty that he and the other Founding Fathers stood for contradict their personal choices….“The Mere Distinction of Color” broadens this connection to include a fledgling America and the ways that slavery was embedded into our country’s government and Constitution without being overtly named.

According to [Christian Cotz, Director of Education and Visitor Engagement at Montpelier], “we wanted to show the thoughts surrounding slavery in the 18thand 19th centuries, and then show how the idea is protected within the Constitution. And we couldn’t leave it there—when the Constitution was written. This is a living, breathing document that has both protected slavery and ended it. But that ending has its own impact and legacy. So we wanted to take that thread all the way to the present and connect these dots.”

The exhibit culminates with a powerful video that reinforces these connections—between the enslaved community and James Madison, between Madison and our country, and between our past and present. The Montpelier Foundation invited 15 black academics, artists, and activists to the site…to create an interpretive video that encompasses slavery’s legacy. In the video. Regie Gibson…is candid about America’s tenuous relationship with our interpretations of the past. ‘I think our problem as Americans is that we actually hate history, so we can’t really connect the dots,’ he says. ‘What we love is nostalgia. We love to remember things exactly the way they didn’t happen. History itself is often an indictment. And people? We hate to be indicted.’

It might seem more comfortable to ignore or soften retellings of slavery’s difficult history and its significant impacts on the present lives of African Americans. But the “Mere Distinction of Color” chooses to instead create an inclusive interpretation of slavery that addresses tough questions about where our national identity stands today.

The Montpelier Foundation also chose to supplant rather than supplement the exhibit about James Madison as Father of the Constitution (two tours a day about the Constitution without any exhibit remain options for the public).

Other Historic Sites and Museums

I should not have been surprised by the revisions at Montpelier; in 2014 I wrote a previous article for NAS, “Academic Social Science and Washington History,” about a similar experience during my service in the first Bush administration in the early 1990s. Then I took a break one day to walk through the exhibit on the founding of America at the nearby National Museum of American History. To my amazement, not a single Founder was to be seen. The exhibit honored a Native American, an African American, and a woman and displayed everyday life and its implements. There was no U. S. Constitution. Rather, a small plaque that declared:

When the American colonies sought to unite during their war with Britain, some leaders thought the [Iroquois] confederacy might serve as a model in some respects for the new American government.

I went on to discuss the museum’s turn to postmodern multiculturalism in its exhibits and described my conclusions from a subsequent visit:

There is still no exhibit about the founding of America or the Constitution. Worse yet, the official “American History Timeline” presented by the museum at its website makes no mention of the U. S. Constitution, which has vanished completely. To find the Constitution in Washington, one must go to the National Archives, but there too, our national heritage has now been corrupted.

I then discussed the new permanent exhibit at the National Archives, called “Records of Rights” and opened in December 2013, which visitors must now first pass through before viewing the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. That exhibit depicts in detail the oppression, throughout our history, of three marginalized groups: African Americans, women, and immigrants.

Edward Rothstein, cultural-critic-at-large for The New York Times, reviewed the gallery’s opening, first observing that after seeing murals of the bewigged founding fathers, a visitor might think that the exhibit would present the ideas of rights from our founding documents.

But then we turn a corner and discover that this promise is not to be fulfilled. Instead, it is turned on its head. We are going to learn not how those ideas succeeded despite flaws, but how deeply, throughout our history, they have failed.

A good part of this should be included in any history of the United States, but here, presented in isolation, without context or deeper analysis, the effect is numbing. We aren’t being asked to think: We are being drilled, unrelentingly, in injustice….

This is a peculiar way for an institution that is a reflection of the government itself, to see the nature of its origins, the character of its achievements, and the promise of its ideas.

In another article for NAS on May 1, 2017, “A Politically Correct Revolution,” I described how the new Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia presents the same kind of one-dimensional narrative about American history and our founding that characterizes our national museums. That narrative prioritizes marginalized groups and common people.

Illustrating this new emphasis, in her review of “A New Museum of the American Revolution, Warts and All” in The New York Times, Jennifer Schuessler wrote, “the common man (and woman) is king.” Historian R. Scott Stephenson, the museum’s vice president for collections, exhibitions, and programming, explained:

Throughout…panels explore the meaning of events for Native Americans, enslaved African-Americans, and other marginalized people. “We call these our ‘wait just a damn minute’ panels,” Mr. Stephenson said. “Every time the language gets a little lofty, we counter it.”…

The Declaration of Independence gallery…focuses not on the soaring rhetoric of Thomas Jefferson but on the raucous dialogue of independent people, who generated more than 80 local declarations. An interactive panel explores the perspectives of 10 individuals: men and women, free and enslaved, enthusiastic and ambivalent.

The “oppression” narrative does not complement the founding ideals and ideas with a more balanced story of our American history. It supersedes or contravenes those ideals and ideas, or assigns them a subsidiary role. Visitors may sometimes still view the physical artifacts and images of our history as exhibits, but the narratives are now ones of oppressed marginalized groups and historic injustice.

Exhibits similar in some ways to that at Montpelier have also been mounted at Thomas Jefferson’s home at Monticello and George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon.

The Meaning of Montpelier

One of the Directors of The Montpelier Foundation, Margaret H. Jordan, a direct descendant of Paul Jennings, James Madison’s enslaved manservant, further explained the meaning of the “Mere Distinction of Color” in an article in The Washington Post on June 30, 2017.

I know that were it not for Jennings and slaves like him, whose labor enabled Madison to follow intellectual interests and pursue his role as architect of the Constitution and then as the nation’s fourth president, our country would not be the same. But how many Americans share that knowledge of our history?…

In the retelling of U. S. history, there has been an incomplete and frequently inaccurate story of African American history. At best, it has been the auxiliary exhibit, with slavery a disconnected footnote in the larger tome of our nation’s story….Most Americans have not been taught to see and embrace African American history as part of their history as Americans. Indeed, in the telling of American history, we have failed to fully grapple with the reality of slavery and its lasting hold on society. This has consequences.

Today, we are fortunate to have two new opportunities to understand our history in its unvarnished form. The opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture put a stake in the ground by establishing the first museum in the nation’s capital to tell the story of our nation through the lens of the African American experience.

In June, I led the invocation of a new exhibition at James Madison’s Montpelier, “The Mere Distinction of Color,” which tells the story of what life was like as a slave on the plantation of our fourth president. Through stories told by living descendants and artifacts gathered over the past 17 years, the exhibition invites visitors to walk in the footsteps of slaves, going beyond the superficial depictions of slave life. By depicting the realities of slavery, and the economic, ideological, and political factors that kept slavery intact in the then-newly created Constitution, the exhibition provides a more comprehensive picture of the founding of our nation.

But on a deeper level, both places invite us to examine not only our painful past but also our present-day biases. They compel us to explore how the legacy of slavery affects our perspectives about race and human rights. And they provide a starting point to have the difficult conversations…that we need to have to move forward as a society. As the “Mere Distinction of Colour” states, “From mass incarceration to the achievement gap, to housing discrimination, and the vicious cycles of poverty, violence, and lack of opportunity throughout America’s inner cities, the legacies of 200 years of African American bondage are still with us.”

It is only through this examination and introspection—of our history in its entirety, of our diverse experiences and of the preconceptions that divide us—that deeper understanding and respect, and ultimately progress, will come. It will not be found by pushing the darkest chapters of our past away but by bringing them into the light.

Ms. Jordan commented additionally in an interview in September 2017 with NBC News, which asked, “Why was the enslaved exhibit necessary at Montpelier? Jordan replied:

There is stuff we have never resolved in America. We must deal with our foundations: slavery was subtly written in [the] Bill of Rights and Constitution—slavery in America was evil because it took away our humanity. Looking at the institutional racism we still face today is in large part because the textbooks are not teaching the truth of our American history in our schools.

In February 2018, Charlottesville’s C-VILLE Weekly reported that “Montpelier staff, in conjunction with the National Trust for Historic Preservation, organized a national summit on teaching slavery.”

The goal? Create a universal rubric that could be used in schools and at historic institutions. Fifty scholars, museum interpreters from around the country…and descendants of the enslaved community convened for a weekend-long series of workshops and discussions, all aimed at creating the framework for teaching the history of slavery that could become a national model. The goal is to roll out the rubric in June.

“We had a shared version that historic sites could play a leading role…in how the nation comes to understand American slavery,” says Hasan Kwame Jeffries, associate professor of history at Ohio State University. Jeffries can be heard speaking in the Legacies of Slavery video about the ‘Disney version’ of history he often sees his students bring into the classroom, and myths associated with that….

“Slavery is bound by time but its legacy isn’t,” he says. “Slavery was an economic system that at its core was designed to extract labor at its cheapest possible cost, and once slavery ends the same impulse that drove slavery continues forward, justified by this belief in white supremacy so that everything we see afterward in terms of race relations, the African-American condition to the development of America is tied to these implications of what slavery was. The things we see today are informed very much so by what happened in the past.”

Montpelier envisions a national role for the slavery-based message of its new exhibit in the future education of America’s schoolchildren.

Overall Conclusions

Let’s review some of the overall lessons of Montpelier and the other historic exhibits I’ve discussed above, along with a few relevant insights from other articles I’ve written for NAS.

It’s ironic that it should have taken the ascendant academic left so long to remove the Constitutional exhibit at Montpelier, for its new progressive order is “post-Madisonian.” The academic left began by dismissing our founding ideals, ideas, and governing principles and replacing them with Herbert Croly’s ultimate objective for progressivism—the “full realization of the democratic ideal” in a new post-Madisonian America—which he described in Progressive Democracy (1915) and I summarized in an article in May 2012. The current academic ideal of Civic Engagement is democracy or democratic engagement to provide social justice to marginalized or oppressed minority groups (factions) through a collective or popular will.

Why is that post-Madisonian? Madisonian Constitutional governance is based on rule of law by elected representatives of the majority to serve the common good of all and control factions—not rule through democracy and collective or popular will to serve the interests of minority group factions.

To reflect the ideology of the academic left, our founding documents have either been removed from our museums and historic sites or presented only through the lens of injustice to oppressed marginalized groups. Now, the Founders are condemned as racists and Western civilization as the sinful source of white supremacy. The Constitution (and its institutions) is now an instrument of racism and injustice, even after the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, numerous Civil Rights Acts and Voting Rights Acts, and fifty years of affirmative action.

For decades, academic social science has been dominated by Marxist ideas, which have failed throughout history, impoverished ordinary people, undermined bourgeois values, and continue to promise a false future to the still marginalized. Now, the academic left often finds our capitalist economic system and bourgeois ethic fatally tainted by slavery and white supremacy, and irredeemably racist.

The American populace, especially among its youngest generations, is already woefully ignorant of our founding ideals and ideas and our governing and economic principles, which they have not been taught accurately in public schooling for decades. Over the same time, American history courses and our elites and the media have already re-focused attention primarily on slavery, oppression, and other negative aspects of our past. I call for the inclusion of balance in education that acknowledges the positive side of our national history, focusing on our political institutions and economic principles, with illustrations of their successful applications. Such an approach would provide a better basis for a future political solution to our differences and challenges than a more racially-based viewpoint, which would likely lead to further division and conflict.

The transformation of Montpelier is one further step in the control—with nary a metaphorical shot being fired—that our progressive academic and cultural elites have achieved over so many aspects of American national consciousness, from our schooling to our historical institutions. This development brings to mind Will Durant’s observation about the demise of the Roman Empire:

A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself within.

Montpelier is one more illustration of why our more traditional Western elites need to find a way to turn the American academy’s influence around before our founding ideals and ideas have been completely forgotten and it is too late to continue to fulfill their promise.

______________________________________________

This article is reprinted with permission from the National Association of Scholars.