The annual controversy over books assigned to freshmen as summer reading is upon us. Spoiler alerts. Odysseus makes it home. Hamlet dies. The Whale wins.

Oh, not those books. We are talking more about White Girls (by Hilton Als, 2013) and Purple Hibiscus (by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 2003). White Girls, as one reviewer puts it, is “an inquiry into otherness” by a writer for the New Yorker, who is a black male. Purple Hibiscus is a novel by a Nigerian woman that depicts the travails of fifteen-year-old girl who has to cope with her violent and cruel, fanatically Christian father.

In 2014, the topmost assigned book (17 out of 341 colleges that have such programs) was Wes Moore’s account of a convicted murderer who shares his name and his beginning as a fatherless black child in Baltimore, The Other Wes Moore (2010). Second on the list (eight colleges) was Dave Eggers’ novel about a woman who works for a privacy-destroying internet company, The Circle (2013), and third was Rebecca Skloot’s account of the poor black woman whose cervical cancer cells were the first human cell line to be kept growing in a lab, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks(2010). In 2015, according to Inside Higher Ed, it appears that Bryan Stevenson’s memoir of his efforts to exonerate wrongly convicted prisoners, Just Mercy (2014) will be the winner.

Books Younger Than Their Readers

For the last six years, the National Association of Scholars has been assiduously tracking all the books selected by all the colleges that do this sort of thing. We call them “beach books,” but the usual term is “common readings.” NAS executive director Ashley Thorne has pretty much single handedly turned a minor campus phenomenon into a subject of widespread controversy—the subject of annual conferences, legislative hearings, and mass media attention. The latest reverberation was a report on July 23 on NPR.

This year 93 percent of the books assigned to “first-years” (the new PC term for freshmen) are younger than the students who are asked to read them. There are many threads to the beach books story, but the extreme youth of most of the books is the most revealing. Why so much emphasis on hot-from-the-presses titles?

We’ve heard three answers. First, the program coordinators insist that the best way to engage students is to bring the author to campus to speak. That makes for a nice income stream for some contemporary writers, and too bad for Mark Twain. He had his chance.

Second, the coordinators tell us they have to meet the students where they are. Many are “book virgins” who reach college never having read any book cover to cover. Such students need to be coaxed by assigning them a book that is “right now.”

And third, the coordinators are convinced that the past is over and done with anyway and, regardless of what the students think, the focus should be on contemporary social issues.

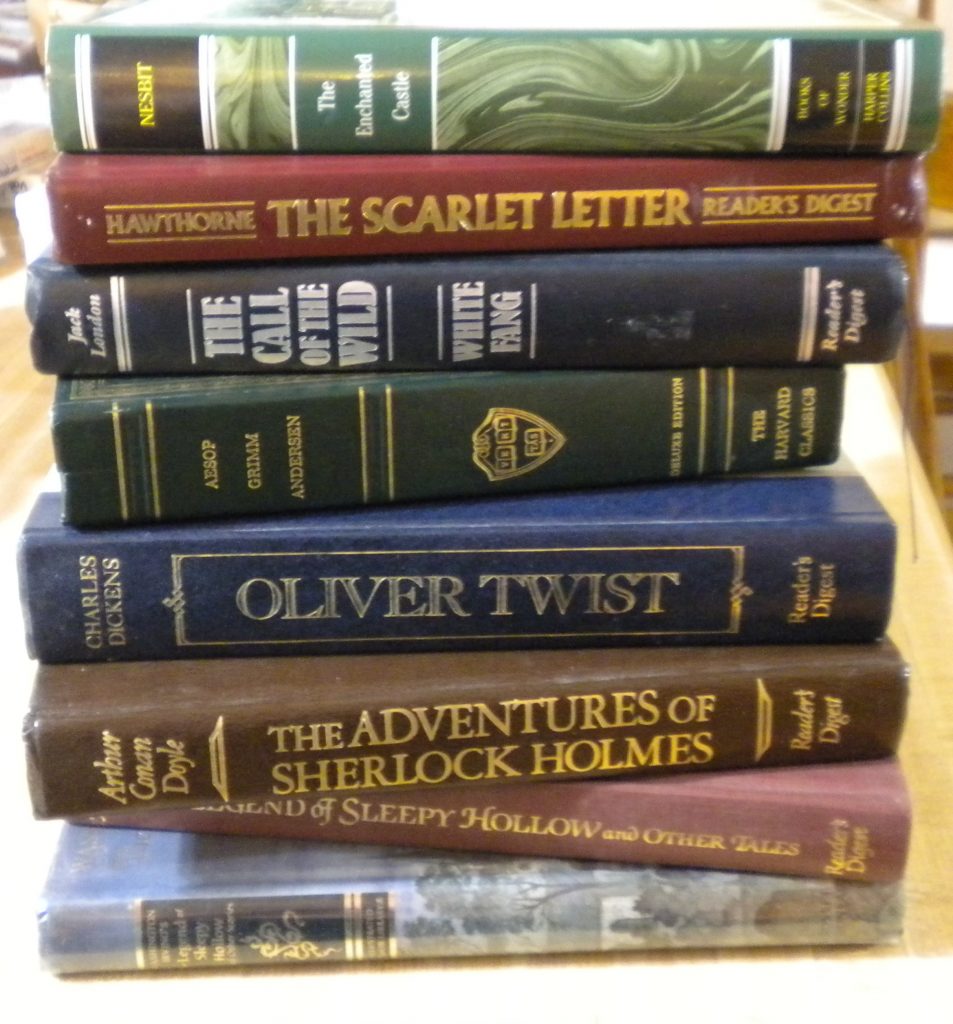

This last one concerns me most, but the other two are lame as well. College students should get used to reading books by dead people. If you can’t read Edith Wharton or Mary Wollenstonecraft without her in the room, hire an actor. As for book virgins and book-o-phobic first years, why not get them started on the real thing? If Hemingway is too hard, try Aesop’s Fables. If Aesop’s talking animals are above their level, try Mother Goose. Am I exaggerating how bereft of literary foundations these students are? I hope so.

No Dead Writers, Please

But the third point—that education all by itself requires that the beach books be molded from the freshest, most up-to-date progressive sand—deserves a little more attention and, let’s say, a lot more opprobrium. Among the responses to the recent NPR report on summer readings came this crystalline summation from an undergraduate named Kai:

Good literature teaches students about our world now, about the challenges our society faces and will continue to face. Climate change, inequity, and—this is the big one—discrimination (especially racial). Real world issues start to be acknowledged when college kids read about them in books like “A Long Way Gone,” “White Girls,” or “The New Jim Crow.” And that’s why college reading programs SHOULD NOT contain the classics. College reading should be controversial, inspiring, provocative contemporary literature.

Kai is full of youthful arrogance. He’s read someone named “Vergil” in the original. But he sees the need to get beyond “institutionalized, oppressive traditions.” The literature that “has shaped the predominant modes of interaction in western civilization” may be “fun to read—indulgent, even,” but it is time to move on.

I don’t mean to make too much fun of poor Kai. He is clearly an eager student who has diligently taken in the premises of his college and enthusiastically made them his own. But his is the voice of someone imprisoned in “now,” for whom “good literature” is writing by contemporary social activists. He is oblivious to the need to learn about the past and the deep ways in which great literature from previous eras bears on the present.

We all, of course, live in the present and need to pay attention to its particular demands, which include listening to people prose on about “climate change” as earlier generations prosed on about other supposed menaces. Inequity and discrimination? Kai might be on firmer ground if he knew more history and understood how much inequity and discrimination are endemic to the human condition. Virgil, for example, has something to say on the topic of oppression.

Devaluing the Past

The saturation of college students in what might be called present-tense books should worry us. Higher education cannot of course erase the past but it can radically devalue it. Introducing students to college-level reading by feeding them candy bars of social outrage is about the poorest way I can imagine to develop their taste for serious ideas expressed with power, imagination, and intelligence.

The problem is not new. We noticed this extreme focus on contemporary books in our first study of common readings in 2010, when we found the “vast majority” of assigned books in the 290 colleges we studied to have been published in the preceding decade. But back then, we did find ten colleges (3.4 percent of the total) that had reached back further. Thoreau’s Walden made an appearance, as did Marx’s Communist Manifesto, Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon, and Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country. More daringly, two colleges had assigned Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

We have redone and expanded the study each year since then. The list of books that are assigned changes dramatically from year to year—as naturally it would if the college is set on chasing the winds of ideological fashion. But what doesn’t change is the relentless focus on books that are in their dewy youth. In 2010, it was the world of Steve Lopez’s account of a skid-row violinist, The Soloist (2008); Greg Mortenson’s account of his building schools for girls in Pakistan, Three Cups of Tea (2007); and Sonia Nazario’s account of a child from Central America illegally slipping in the United States, Enrique’s Journey (2006).

The Soloist is now off playing by himself in a different skid row. Mortenson’s cup ran dry when he was exposed as a fraud; those Pakistani girls’ schools were made up. Enrique went underground for a while but has resurfaced in view of current illegal immigration.

The relative youth of a book is no knock against it as a book, but it is a knock against making it the one (and usually only) book that a class of college students will read together. I’ve elsewhere made my own suggestions for better books for the first-year beach babies. I’m moderate about this. If Don Quixote is too long and Crime and Punishment too dark, try The Right Stuff or Life on the Mississippi, or perhaps better yet, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty.

This article was originally published on the National Association of Scholars site.

On the positive side, freshmen don’t complete the assigned readings.