Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the soon-to-be-published National Association of Scholars report, Rescuing Science. It has been edited to align with Minding the Campus’s style guidelines and is cross-posted here with permission.

Recently, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) proposed that indirect costs rates (administrative overheads) on research grants from the NIH would be capped at 15 percent of a grant’s so-called direct costs, which is the cost for science. This proposal prompted heated rhetoric from universities that this reduction would devastate their research programs. A similar proposal in 2017 provoked a similarly hysterical reaction.

In a previous article, I explored the effect the proposed reduction of indirect costs rates would have on the finances of a typical mid-level research university—anonymized as XU. That article concluded that XU had ample capacity to absorb the reduction in indirect costs rates without harm to its research program. Adjustments would have to be made in other areas of university operations, such as reduced salaries, employment numbers, investments, acquisition of real property, and capital projects, none of which seemed beyond what universities always do in managing their finances.

The hot bone of contention over indirect costs turns on what, precisely, they should be. Universities claim that high indirect costs rates are appropriately high and, in fact, should be higher. Some manage to pull off the trick: the national average for indirect costs is 53 percent of direct costs, but these can be as high as 60-70 percent at some universities. On the other hand, industrial R&D labs set their indirect costs much lower, on the order of 10-15 percent, as do private foundations that issue research grants to universities. U.S. indirect costs rates are also two to four times higher than they are for other countries with national scientific research programs. If universities are being overcompensated for their true overhead costs, then the reduction of indirect costs rates would be a necessary correction.

Getting to a clear answer on these questions is hindered by clouds of misunderstanding and misinformation about what indirect costs are and what they are paying for. For example, a recent article defended high indirect costs rates because they supposedly provided universities the means to offer generous startup packages as recruitment incentives for new faculty. Such practices are very likely disallowed under the rules that govern indirect costs, as CUNY’s Hunter College found out to its detriment a few years ago.

To clarify: the problem is not indirect costs per se. Overheads are a legitimate expense for research, and universities can legitimately seek reimbursement for them. The problem is how rates are set and defining what may, and what may not, be claimed as a legitimate overhead expense. This is where the clouds start to roll in.

A research project’s budget consists of two parts.

Direct costs include salaries and benefits of the scientists and ancillary personnel doing the work, supplies, equipment, necessary travel, and publication charges, among others. Indirect costs are the administrative overheads for accounting, auditing, compliance with labor and safety laws, maintaining the facilities for the research to be done, and so forth.

The essential concept in determining overheads is incremental cost, which is the additional administrative burden that accrues to hosting a research project compared to not hosting it. Here’s the big problem with indirect costs: calculating the incremental cost can range from being merely difficult to impossible.

At the merely difficult end of the spectrum are estimating incremental costs of research contracts. These are projects that are built around known deliverables, set timelines, and specified plans of work. If, say, the Navy wants a table of physical properties of a novel alloy, it can contract with a testing laboratory to provide it, to a specified standard and project timeline. If a contracted project consumes 10 percent of a laboratory’s total efforts, calculating incremental cost is an accounting and reporting problem: rigorous record-keeping of administrative time, effort, and resources, as well as ancillary issues like laboratory maintenance, depreciation of equipment and facilities, and so forth. Calculating indirect costs for research contracts is straightforward but it requires effort to implement.

Most university research, in contrast, is supported by research grants, which are distinct from research contracts. The distinction turns on the type of research that universities typically support, that is to say basic research, also known as curiosity-driven research. Unlike a research contract, there can be no deliverables for basic research, because they are unknown, and indeed, are unknowable. This is the whole point of basic research. Nor does curiosity-driven research proceed along a predictable timeline, as expected in a research contract. Time and effort vary with the ebb and flow of creativity, inspiration, and opportunity. None of these are specifiable for basic research. Finally, unlike the focused mission of a research laboratory, the university has two core missions—teaching and research—that are seamlessly integrated with one another. They cannot be neatly partitioned like research contracts can. All these factors, and more, make it impossible to estimate incremental costs with any reliability. Despite this, our current system of federal funding for basic research supposes that they can be, so the same administrative principles that apply to research contracts are applied to research grants.

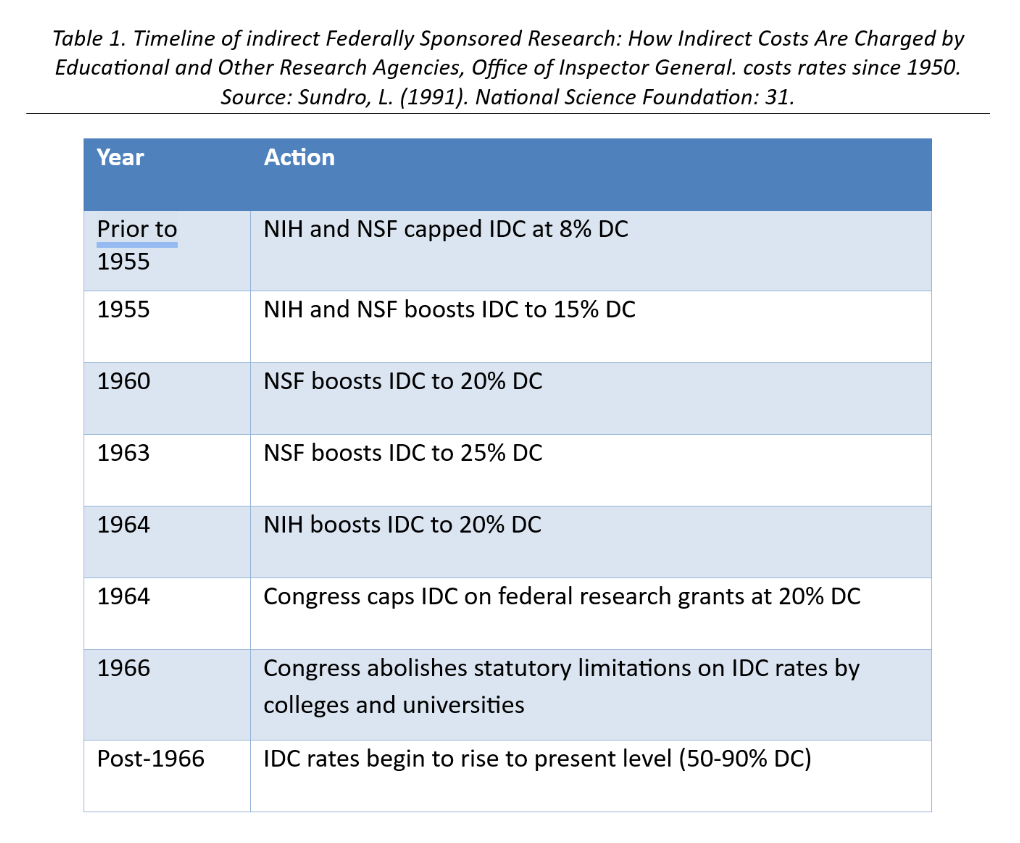

The most visible evidence of this incoherency has been the unmooring of indirect costs from the restraints that normally would hold them in check (Table 1). Prior to World War II, government overheads on research contracts were set at eight percent of direct costs, in line with industry standards for incremental costs. When the NIH began to issue research contracts to universities in 1943, the eight percent standard applied. In 1950, the newly-established National Science Foundation initially adopted the eight percent standard, but raised them to 15 percent in 1955, then to 25 percent. The unmooring began in 1966, when Congress—which previously had set indirect cost rates by statute—opted for rates to be set through negotiated agreements between universities and funding agencies, to be renegotiated every three years. After that, indirect costs rates were set on an upward trajectory to their present high rates, which are considerably higher than the 10 percent overheads most charitable foundations are willing to pay, and are two to four times higher than indirect costs rates for other countries with national scientific research programs.

Paradoxically, the upward drift of indirect costs rates has occurred under a regulatory regime intended to control them. Since 1966, the terms of the negotiations between universities and the federal government to set indirect costs rates have been laid out by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in Circular A-21. Cost Principles for Educational Institutions, last revised in 2004.

Circular A-21 was intended to bring clarity and consistency to what may, and may not, be claimed as indirect costs. So, for example, depreciation of facilities and equipment constitute legitimate indirect costs, as well as operations and maintenance of buildings and grounds that are used for a university’s research mission. Alcoholic beverages, flowers and furniture for the president’s office, yachts, costs of lobbying legislators, slush funds for researchers, and exotic dancers do not. (All are actual instances of indirect costs abuse.)

The rules laid out in Circular A-21 appear to be very strict. In its sixty-seven printed pages, 129 examples of “unallowable” charges are listed. The strictures are deceptive, though. During their triennial negotiations, universities and funding agencies will inevitably disagree over various points, such as how to structure a depreciation schedule. The standard the OMB sets for resolving these disagreements is the “prudent person” standard. Where some difficult or arcane point of disagreement crops up (such as over the details of a depreciation schedule), “reasonableness” is to prevail. Some variation on the word “reasonable” appears fifty-nine times in the document, indicating the broad range of issues for universities and the cognizant agencies should be “reasonable” about.

While reasonableness can be a useful lubricant for negotiations, which way the compromise slides depends upon which party pushes the hardest. The climb of indirect costs rates since 1966 indicates that the stronger shoulder in the negotiations has been the universities’. The best that can be said in defense of the “Circular A-21 regime” is that indirect costs rates are not as high as universities would like them to be.

To be fair, Circular A-21 attempts an impossible task: apply the costing principles for research contracts to grants for basic research in universities. Negotiations between universities and funding agencies are beset with conundrums that are impossible to resolve. How, for example, does one parse out the incremental research cost of a university library that is used for both the university’s teaching and research missions? Arguably it cannot be, nor should it be: in a university, teaching and research are rightfully inseparable. Nevertheless, the rationale underlying Circular A-21 regime is predicated on an imagined ability to do precisely that.

Shoehorning Circular A-21 into a task it is totally unsuited to do has produced a rococo edifice of revenue pools, time and effort accounting, complicated financial models, and other decorations and filigrees that produce what Roger Noll and William Rogerson have characterized as Precisely Calculated But Arbitrary (PCBA) estimates of universities’ overhead costs. There’s a great deal of slipperiness in those PCBA estimates, and this is the principal reason why indirect costs rates are so high in the American research ecosystem. When combined with the manageable impacts of reduced indirect costs on universities’ finances (XU audit article), the hysterical reaction of universities to any proposal to reduce indirect costs rates is laughable.

Any debate about indirect costs rates has to take the failure of the Circular A-21 regime into account. Otherwise, the discussion boils down, as it now has, into quibbling over details that do not address the incoherency at the heart of the problem. A better solution would ditch the Circular A-21 regime altogether and replace the current phony regime of negotiated indirect costs with a simple flat rate for overheads—essentially the current proposal to cap indirect costs at 15 percent of direct costs. This would obviate the need for the complex and impenetrable negotiations mandated by Circular A-21, and would simplify and clarify the public’s right to accountability for the funds they provide. It would also bring federal overhead reimbursements more in line with private grant funding, which commonly cap indirect costs rates at 10 percent.

Finally, a capped flat rate would have the salutary effect of weaning universities off the entitlement mentality that currently prevails. Why should universities expect the federal government to fully fund a university’s core mission? Why can’t universities be expected to bear the primary responsibility for funding their core missions? If a university has a good reason to charge high indirect costs rates, as many now do, why can they not be expected to bear the extra cost themselves? And if a university can manage their overheads more efficiently and economically, why should they not reap the benefits of being fiscally responsible?

Follow Scott Turner on X and visit our Minding the Science column for in-depth analysis on topics ranging from wokeism in STEM, scientific ethics, and research funding to climate science, scientific organizations, and much more.

Cover by Jared Gould using Grok

This is an excellent essay, and excellent report. It elevates the discussion with fact and data. More, it clarifies some mechanical complexities of university administration, which is not generally well understood among its constituents. It is the kind of model response university governance should voluntarily pursue in its communications, in order to conform more to a rational empirical posture. Congratulations.

The question I have is how much research did universities do a century ago?

How much should we be spending on research and how much should we be spending on undergraduate education? And non-research graduate education, i.e. grad degrees that are necessary for employment outside of the research field — e.g. MD.

Conversely, how much is research a necessary expense not unlike dormitories?

I am an educator and do not apologize for that — I believe that the primary purpose of higher education ought to be to educate. And other than the lucrative indirect cost revenue, why are universities doing research?

Particularly in the humanities….