I have previously reported through two Minding the Campus articles (here and here) that the National Science Foundation (NSF) director, Sethuraman Panchanathan, published a paper through the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) that copied an uncited source previously published through the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

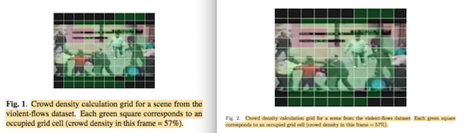

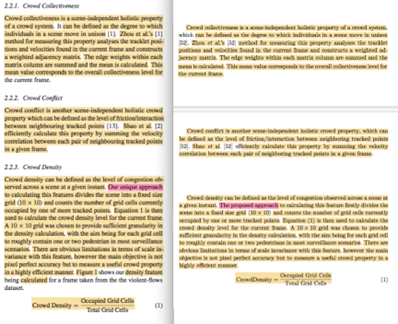

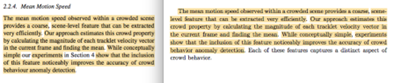

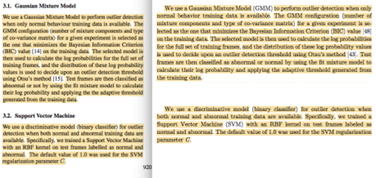

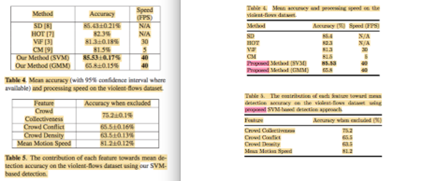

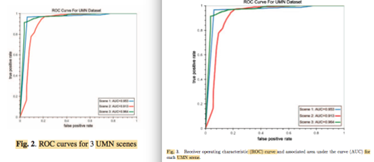

In addition to copying from IEEE for his ACM article, Panchanathan also published a paper through IEEE that copied an uncited source published by ACM. His duplication of copyrighted material doesn’t end with ACM and IEEE. A comment on the PubPeer website described how Panchanathan’s World Scientific paper, “Enriching the Fan Experience in a Smart Stadium Using Internet of Things Technologies,” copied two-thirds of the IEEE-copyrighted paper “Holistic features for real-time crowd behaviour anomaly detection” without indicating permission of the copyright holder.

The World Scientific version did not enclose copied passages in quotation marks or acknowledge the source of its tables and figures. It repeatedly described, as a “proposed approach,” methods that were previously published in the IEEE version. It also added six authors who took credit for the material copied from the IEEE version.

The work was funded by NSF award 1069125 for a total of $3 million. NSF doesn’t allow grant recipients to use its funds for research misconduct such as plagiarism and falsification, per its rules. Examples of the duplication are shown below, with the IEEE version on the left and the World Scientific version on the right.

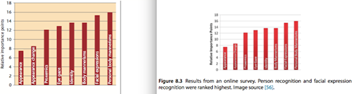

Another comment on PubPeer described how Panchanathan’s Academic Press paper “Computer Vision for Augmentative and Alternative Communication” copied a third of the IEEE-copyrighted paper “Person-Centered Multimedia Computing” without indicating permission of the copyright holder.

The Academic Press version didn’t cite the earlier IEEE version. It replaced one of the original co-authors with two others. Examples are shown below, with the Academic Press version on the right.

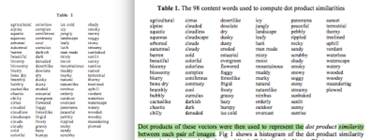

In addition, it was reported that 85 percent of a Springer paper Panchanathan came from a paper copyrighted by IEEE without indicating permission of the copyright holder.

The Springer version did not enclose copied passages in quotation marks or cite the source. It was under review while the IEEE version was already covertly in press. The Springer version falsely claimed to “propose” a method already proposed and published. Examples are shown below, with the Springer version on the right.

It was also reported that Panchanathan published a paper with the Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) that copied approximately three-fourths of an IEEE paper and text and all figures from a Springer paper. The SPIE version did not enclose copied passages in quotation marks, did not cite the sources, and did not indicate permission of the copyright holders. It added gift authorships for Panchanathan’s students, Kanav Kahol and Prem Kuchi, who thereby took credit for the words and ideas of others.

Examples are shown below, with the SPIE version on the right.

It was further reported that Panchanathan’s Elsevier paper “Reconfigurable Media Processing” copied approximately one-fourth of the text from an IEEE paper without indicating permission of the copyright holder.

The Elsevier version did not enclose copied passages in quotation marks, did not cite the IEEE paper, and did not include three of the original co-authors, thereby taking credit for these authors’ words and ideas. It also made false and misleading representations of novelty, claiming to “propose” a “novel” approach that had already been proposed and was no longer novel. Examples are shown below, with the Elsevier version on the right.

In January 2024, Harvard released its report on alleged plagiarism by its president, Claudine Gay. However, there was one notable thing the report did not address: were the instances of uncited copying “plagiarism” or not?

Instead, the report explained that Gay’s conduct “did not constitute research misconduct as defined by the FAS Research Misconduct Policy.” The Harvard Corporation settled the matter by saying it “found no violation of Harvard’s standards for research misconduct.” The conclusion side-stepped the central question of whether Gay “plagiarized.” Moreover, it demonstrated that the Harvard research community’s “accepted practice” includes uncited copying—even if it is “plagiarism.”

The NSF director’s publication practices were evaluated by a constellation of publishers, including ACM, IEEE, World Scientific, Academic Press, Springer, SPIE, and Elsevier—these are some of the leading publishers of science and engineering research. Readers and subscribers naturally wonder whether prohibitions of plagiarism, self-plagiarism, falsification, and copyright infringement are made in good faith or are instead a form of fraudulent false advertising by these publishers.

You, the reader, will be shocked to learn that none of these publishers answered my questions of whether the NSF director infringed copyright, plagiarized, self-plagiarized, or falsified in the examples shown above. One of the publishers—ACM—instructed me through its lawyer never to communicate with them again. Another—IEEE—simply ignored my requests. The other publishers were kind enough to acknowledge receipt of my questions, but although months have elapsed, they still haven’t decided if the NSF director’s uncited duplication of copyrighted material by other authors violates any of their ethical policies.

More than two dozen of Panchanathan’s publications have been flagged on PubPeer. But this situation creates something called “actionable information.” If you are a researcher, you might be tempted to inflate your publication count by copying work that was previously published. The editor, the reviewers, and the readers might be concerned if the work was previously published and copyrighted by another publisher. So, you certainly wouldn’t want to tip them off. It’s, therefore, a good idea not to list the original source among your references. That way, maybe nobody will be aware that you are republishing work.

The editor and reviewers would similarly be suspicious if most of your paragraphs were enclosed in quotation marks. Doing that would make them realize that most of your manuscript was copied. The solution? Don’t use quotation marks, and don’t cite the source you copy from.

And don’t ask for permission from the copyright holders—they might say no. Also, don’t admit that your “novel” method was already published before, and don’t cite the source where the method was initially published. In addition, if you have students or colleagues needing more publications, add their names. You will be helping advance their careers by teaching them how to inflate their publication records.

If you use this one weird trick enough times, you, too, might become the director of a federal research agency. However, you and your agency will have a conflict of interest, rendering you utterly incapable of finding misconduct among the researchers you fund with billions of taxpayer dollars. If anyone in your agency admitted that constitutes “misconduct,” that determination would apply to the publication record of the agency head. But nobody wants to submit a report to the agency head insinuating that the agency head committed misconduct.

Cover designed by Jared Gould using image of Sethuraman Panchanathan on Wikipedia and “cut copy paste” by KE4 on Flickr.