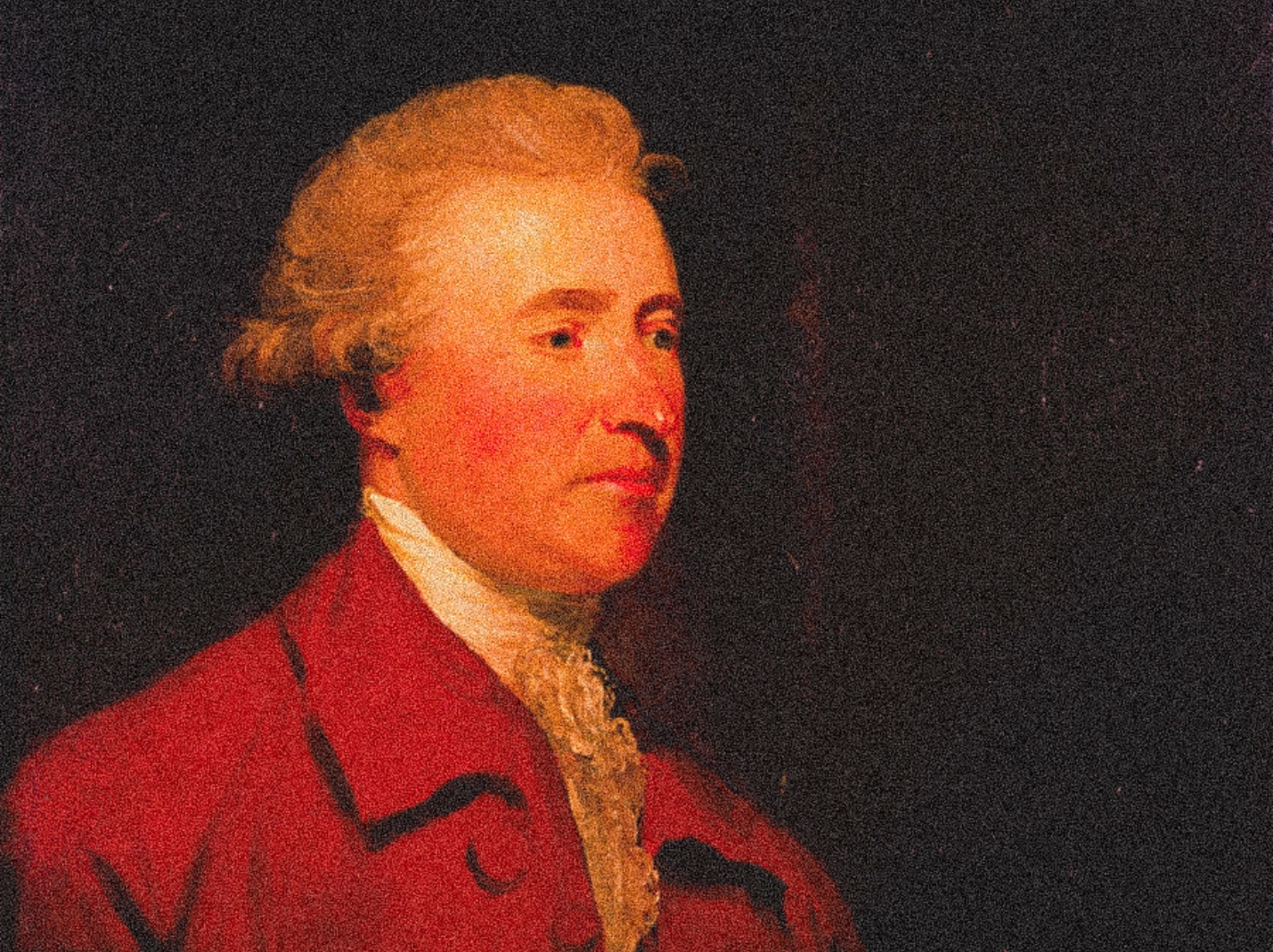

On March 22, 1775, Edmund Burke delivered one of his great Parliamentary orations on Conciliation with America. Britain and America were rushing to war, and Burke pulled out the stops to make an extraordinary peroration for peace. Britain’s current policy was worse than unjust—it was doomed to fail. Peace must be achieved, argued Burke, by a change of policy on the part of Great Britain.

Burke’s audience was the House of Commons, not America. To them, therefore, he described America’s spirit of liberty both in flattering terms—and as an objective fact which politicians must account for in their policies.

In this character of the Americans, a love of freedom is the predominating feature which marks and distinguishes the whole; and as an ardent is always a jealous affection, your Colonies become suspicious, restive, and untractable whenever they see the least attempt to wrest from them by force, or shuffle from them by chicane, what they think the only advantage worth living for. This fierce spirit of liberty is stronger in the English Colonies probably than in any other people of the earth …the people of the Colonies are descendants of Englishmen. England, Sir, is a nation which still, I hope, respects, and formerly adored, her freedom. The Colonists emigrated from you when this part of your character was most predominant; and they took this bias and direction the moment they parted from your hands. They are therefore not only devoted to liberty, but to liberty according to English ideas, and on English principles … The people are Protestants; and of that kind which is the most adverse to all implicit submission of mind and opinion. This is a persuasion not only favorable to liberty, but built upon it.

Americans must look back with delight upon this portrait—as flattering to us as Burke’s artistic contemporary George Romney’s portraits were of his noble patrons. Burke also meant to flatter his auditors; Cousin Jonathan over the water was just John Bull distilled. But it was part of a larger argument of prudence and accommodation: Cousin Jonathan loves his liberty, he is one of some swiftly increasing millions three thousand long miles away from the center of our power, and we must govern him accordingly.

Burke advocated that Parliament use the lightest of reins—that it rescind the Boston Port Bill and all other needless—as he saw them—aggravations of the American colonists. Cease to irritate the Americans, and they would return to their natural love of England.

The Americans will have no interest contrary to the grandeur and glory of England, when they are not oppressed by the weight of it; and they will rather be inclined to respect the acts of a superintending legislature when they see them the acts of that power which is itself the security, not the rival, of their secondary importance… for all service, whether of revenue, trade, or empire—my trust is in her interest in the British Constitution. My hold of the Colonies is in the close affection which grows from common names, from kindred blood, from similar privileges, and equal protection. These are ties which, though light as air, are as strong as links of iron. Let the Colonists always keep the idea of their civil rights associated with your government,—they will cling and grapple to you, and no force under heaven will be of power to tear them from their allegiance.

Burke’s speech is magnificent, and there are some great truths in it. Indeed it is true that Americans were greatly imbued with a love of libertyand that the heirs of Oliver Cromwell in New England and of Algernon Sidney in Virginia were not likely to acquiesce for long in coercive English rule. So, too, is it true that a British policy based on loose rein and trust in affection toward Great Britain could work. The entire nineteenth- and twentieth-century British imperial policy of devolution, of Dominion and Commonwealth, was based upon Burke’s a prioris—and worked. In 1939, Britain’s Dominions freely voted to join Britain in war against Nazi Germany—in Canada, in Australia, in New Zealand, even in South Africa, where the Afrikaner voting majority had much reason to dislike the British who had conquered them. A long-term British policy of trust in colonial affection could and did work.

[RELATED: The American Revolution Series]

Yet, Burke’s argument is not entirely persuasive. Set aside that it is a liberal speech in the worst sense as well as the best—a speech that argues for weakness from principle, that shrinks far too readily from the exercise of force in the exercise of the national interest, that urges reasonable men to bend to the will or the unreasonable. Burke does not realize that Cousin Jonathan already had lost too much of his love for Great Britain—and irretrievably. Neither does Burke remark that Cousin Jonathan had also been reading French books, and increasingly he thought of his rights as natural to all mankind, and not just the rights of Englishmen. And then, he is gravely mistaken in his contention that Americans will have no interest contrary to the grandeur and glory of England. Our forefathers in the 1770s had an intelligent appreciation that the entire North American continent north of Mexico was up for grabs and a rational ambition that the empire to come be centered from Boston to Charleston and not from London. In 1775, neither affection nor interest still bound America to Britain.

Burke’s speech was magnificent, wrong-headed—and ineffective.

The majority of Britain’s Parliament was set on confrontation with the colonies. What little affection truculent Cousin Jonathan still had for Britain would leak away with the bloodshed at Lexington and Concord. Perhaps Britain might have succeeded had it set out in 1763 to make America a loving Dominion avant la lettre—but by 1775, such a policy could not succeed. The beauty of Burke’s words could not hold back the British Empire from its trans-Atlantic civil war.

In 2025, we are in the middle of a—more bloodless—civil war across the American imperium.

The Patriot rebels have seized control of the White House—but they face entrenched and mighty opponents in the bureaucracy, the judiciary, half the state governments, civil society, and the Old Regime’s client bureaucracies that rule Europe and our other protectorates. The Patriots’ only true source of power is the American people—but that is a mighty champion.

How do the lines of affection and interest run? When should coercion and confrontation be used, and when should conciliation and the loose rein? The protagonists of our conflicts today must ponder these questions, with Burke’s wisdom only fitfully reliable as a guide.

Perhaps we should substitute the phrase the federal government for England: “The Americans will have no interest contrary to the grandeur and glory of the federal government, when they are not oppressed by the weight of it.” Will Americans be conciliated to our federal government if it is depoliticized? Will they be happy with an expansive federal government purging its woke excrescences? Or is their disaffection so deep that they would rather all grandeur and glory belong to the American people and not to its government?

I hesitate to identify one person as the Edmund Burke of our day—amiable, well-meaning, but ultimately out of touch with the temper of the times. I suspect my own policy recommendations are a mixture of Tom Paine and Edmund Burke, and many of us who start out as Paines end up as Burkes. I do fear that Oren Cass, whom I generally support, and many of whose policies to reform conservative economic policy are revolutionary, may be showing a too-Burkean caution in his recent reservations about the Department of Government Efficiency. But if I name Cass, it is because I see him as I see myself—someone caught off guard by just how swiftly the Patriots of our day have moved to put into effect the American people’s disaffection with a government that has been perverted into an institutionalized conspiracy against their liberty.

I suspect that it is far too late in the day to conciliate the American people to our federal government. But we shall soon discover the truth of the matter.

Follow David Randall on X, and for more articles on the American Revolution, see our series here.

Art by Beck & Stone

“January 6th wasn’t particularly violent as these things go (no more than some BLM protests)–it’s significance was that it was an attempt to stop a peaceful transfer of power”

Someone’s clearly never heard of Mount Weather…

On April 19th, Boston had/has a 13.5 hour day, with first light at about 4:40 and sunrise at 5:45 by their clocks*. It’s 15 miles from Cambridge to Concord via a modern (direct) highway, if one was to go by way of Arlington (Menotomy) and Lexington, it would be about 20. Four miles an hour is a top marching speed for fresh, fit, troops.

In this case miserable troops with mud-filled wet boots, but I digress.

Gage had already lost the element of surprise — he was aware that the townsfolk were speculating that the troops would be going after the cannon in Concord and he should have aborted the mission then. It definitely should have been aborted in Lexington — better to have another Leslie’s Retreat than to start a shooting war.

And if he knew that the Provincial Congress was debating the need for armed resistance, which he reportedly did, why on earth would he give them a reason to do so?!?

After Leslie’s Retreat a few months earlier, Edmund Burke had written “Thus ended their first expedition, without effect, and happily without mischief. Enough appeared to show on what a slender thread the peace of the Empire hung, and that the least exertion of the military power would certainly bring things to extremities.”

The Powder Alarms had shown Gage that he was outnumbered, and he knew he was dealing with men who were not only trained but (largely) were veterans of the French & Indian Wars. So what was he trying to accomplish?

Edmund Burke was a Whig. The Whig Party controlled the British government from 1715 until King George III arrived in 1760. Yes, that King George….

And this is why I start to wonder about British politics.

The Province of New Hampshire was sandwiched between Massachusetts, then and now with only 19 miles of coastline in a country that was then concentrated along the shore. While Governor Benning Wentworth had been a problem, selling land in what technically belonged to New York and would become Vermont in 1791; John Wentworth, who replaced him in 1767, was a competent Royal Governor who managed to peacefully resolve things.

For example, his tea shipment didn’t wind up in Portsmouth Harbor — instead it was peacefully loaded onto another ship and sent to Nova Scotia. I maintain that, but for nearby Massachusetts (and Gage’s exacerbation of things) New Hampshire would have remained loyal to the Crown.

Of course the Revolution — in Boston — was also a civil war. Not so much in New Hampshire and I’m not sure why.

—

* This is based on noon being defined as when the sun was directly overhead, as it was before standard time zones were introduced. I am using figures for April 19, 2025 and adjusting on the basis of noon being 6.25 after sunrise.

I would think a “Director of Research” would be cognizant of the fact that the “Olive Branch Petition” was sent to Britain by the Continental Congress in July of 1775, _after_ the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord (April 1775). So not only was reconciliation possible, it was also desired by the colonists. King George the 3rd refused to accept the petition, incidentally, but if he had heeded Burke’s counsel the revolution might well have been averted.

First, a little bit of geography — at the time Boston consisted of the 789 acre Shawmut Peninsula, glacial dump that would have been an island except for a 100-foot-wide moraine that ran south to the then town of Roxbury. It was surrounded by salt marshes, both the Charles and Mystic Rivers were tidal estuaries. (Since 1910, the water level of the Charles River has been regulated by dams, the 1978 dam also has six large pumps to lower the river when it goes too high.)

The causeway was only 100 feet wide at high tide, with impassable mud off to both sides during low tide. Tides in Boston run 8 to 12 vertical feet, depending on the Moon, and this would have exposed significant mudflats but (like most estuaries) it was a fine mud that reportedly was “impassable.” Since the 1600s there had been a wall and gate on the causeway and General Gage had expanded & reinforced this, adding a ditch in front of it that filled with water at high tide.

After Lexington and Concord (and being shot at on the way through Arlington — that’s where the British lost most of the men they did), the British retreated onto their island and the Minuteman laid siege to it. The environment became hostile to Loyalists, e.g. NH Royal Governor John Wentworth retreated to Boston after a cannon was pointed at the front door of his house.

And then on May 10th, less than a month later, Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold captured Fort Ticonderoga — that winter, Henry Knox would somehow manage to bring the fort’s cannons down through Western Massachusetts and the following March they would be erected on the Dorchester Hills overlooking Boston. That led the British and Loyalists to evacuate to Halifax, NS (a much shorter distance by water).

And the next day, the rebels seized the nearby Fort Crown Point, seven days later they raided Fort Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River in southern Quebec, seizing military supplies, cannons, and the largest military vessel on Lake Champlain.

By contrast, all the Confederates did 86 years later was fire on Fort Sumter and the Civil War started.

And while I doubt the British knew it at the time, the same Congress that sent the “Olive Branch Petition” also authorized Benedict Arnold to hike up what is now US 201 and attack Quebec. That didn’t go well, nor did his subsequent Penobscot expedition where he sank his ships in what is now Downtown Bangor — they found one in the 1950s and another in the 1980s when bridges were being built across the river. And then we all know what he wound up doing in the end.

But why, exactly, would you expect King George III to consider a peaceful solution once the war had already started — it would have been one thing if it was just Lexington & Concord — that would have kinda like Kent State — but then the trip through Arlington, the siege of Boston, and then the loss of Fort Ticonderoga, like, umm…..

If you want peace, prepare for war. The colonists did both. I see no contradiction in asking for negotiations while preparing for the possibility they may fail (see below).

>

But why, exactly, would you expect King George III to consider a peaceful solution once the war had already started — it would have been one thing if it was just Lexington & Concord — that would have kinda like Kent State — but then the trip through Arlington, the siege of Boston, and then the loss of Fort Ticonderoga, like, umm…..

<

What I expect or do not expect has no influence on the actors 250 years ago, unless one has some sort of teleological theory of historical events. I think modern readers are simply unaware about how frequently rebellions occurred in the 18th and previous centuries, and how often they were settled–sometimes by force, sometimes by agreement. January 6th was a surprise only to those ignorant of history.

I have trouble taking seriously anyone who considered the January 6th Fratparty to be a rebellion or even an insurrection — I saw a *lot* worse at UMass Amherst when the Red Sox won the World Series in 2004.

Without going into a lot of other things, I will ask the most basic (and most visible) question — where were all the cops? The few times I have been down to Capitol Hill, there were police officers *everywhere* — nice enough people, quite helpful in giving directions, but a very visible police presence. And on January 6th they weren’t there.

That said, and notwithstanding the aspects of a concurrent civil war, which it very much was, I blame the Revolution on British incompetence. My personal favorite is that while the British Army was at war in 1775, the British Navy wasn’t, and hence wasn’t patrolling Boston’s outer harbor (the whole thing is a natural harbor formed by various islands, several of which are now under Logan Airport).

This led to the situation where British supply ships would routinely be captured by the Americans — within sight of the British in Boston — who couldn’t do anything because this was happening upwind of them, in the days of sail.

You assume that King George III could even read the petitions if he wanted to — I don’t. He was from Hanover, i.e. German, and reportedly could barely speak English — a point Ben Franklin pointed out when it was proposed to make our national language German (because people were so unhappy with the British).

Yes, there have always been rebellions, but John Brown’s raid was somewhat different than firing on Fort Sumter, and Shay’s Rebellion would have been quite different had they captured the Federal Arsenal in Springfield (MA).

Had it not involved the capture of the forts hundreds of miles away, maybe — but that’s like saying that maybe the Progressive Democrats and MAGA Republicans cam get along with each other today.

Remember that Edmund Burke was a Whig (and from Ireland, born in Dublin) and that the Whigs had been in total control of the Government until George III permitted the Tories back into power. So if, say, Senator Warren (D-MA) — a.k.a. “Pocahontas” — were to write a letter to President Trump, how well would he read it?

I guess I have to reply to the previous comment as the threading has hit a limit. January 6th wasn’t particularly violent as these things go (no more than some BLM protests)–it’s significance was that it was an attempt to stop a peaceful transfer of power. Politics is what we do before we start shooting at each other. When the political process is interrupted by force, we are in rebellion.

Regarding the British, they did learn their lesson–they had no more rebellions in their “second” empire (of the countries colonized primarily by English settlers–Canada, Australia, New Zealand–the African/Asian colonies had too many natives to push aside). King George would have had the petition read (and translated) if need be by his advisors. Warren could go on Fox News at any time she wished to speak (in)directly to Trump.

Academic political scientists have looked at why American democracy exists, given that most Americans actually don’t believe in such things as civil liberties (ask people to sign a petition which consists of the Bill of Rights and three-quarters will refuse). They came to the conclusion American democracy exists because elites believe in it. That is increasingly the case, and the attacks came first from the academic left (speech codes/drumhead tribunials/etc). Now the right is answering in spades. We are not in quite as bad a situation as the antebellum period (where many Congressmen were armed on the floor of the House, and slavery was forbidden to be discussed), but the situation is not good.