Tufts University in the Boston, Massachusetts metro area ranks 37th on the U.S. News and World Report and boasts an endowment exceeding $2 billion. Between 2019-2023, the American public funded Tufts research to the tune of $230 million per year, primarily through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Department of Education (ED).

Like its Boston neighbor, Harvard, Tufts promulgates a policy that carves out a special exception in research misconduct. There will be no finding of misconduct when the activity in question is an accepted practice within the research community; research misconduct requires there “be a significant departure from accepted practices of the relevant research community.” Harvard used this one weird trick to excuse its former president, Claudine Gay, from plagiarism charges: the Harvard Corporation “found no violation of Harvard’s standards for research misconduct” in Gay’s “duplicative language without appropriate attribution.”

Retracted Papers Authored by a Dean at Tufts

In 2005, Robert J. Sternberg became Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts. The following year, he published “The Nature of Creativity,” which was later retracted because it “contains a substantial amount of content previously published by the same author in Creativity and Development (Sternberg, R. J. (2003).” Another of Dean Sternberg’s papers was retracted because it became “known that a substantially similar article by the same [author] was published previously in Journal for the Education of the Gifted (Robert J. Sternberg and Elena L. Grigorenko, Teaching for Successful Intelligence: Principles, Procedures, and Practices, Journal for the Education of the Gifted, Volume 27 (2–3). DOI 10.1177/016235320302700206).”

He co-authored the paper with his doctoral student Elena Grigorenko; they copied each other and, therefore, abetted each other. And another paper by the dean was flagged because it “contains text that has been previously published by the author.” So was another—and another. His “New Model for School Psychology” was retracted because it wasn’t a new model after all but instead included “substantial unreferenced overlap” with his earlier papers.

Dean Sternberg’s article “Whence Creativity” was flagged because it “contains text that has been previously published by the author,” and another article was retracted due to “substantial overlap with the author’s previously published works.” This particular article with “substantial overlap” discussed unethical leaders:

[P]eople may allow leaders to commit wretched acts because they figure it is the leaders’ responsibility to determine the ethical dimensions of their actions … We would like to think that the pressure to behave ethically will lead people to resist internal temptations to act poorly. But often, exactly the opposite is the case.

In retrospect, his words take on a confessional character:

Ethical drift is the gradual ebbing of standards that can occur in an individual, a group, or an organization as a result of the interaction of environmental pressures with those subjected to these pressures. It often occurs insidiously and even without the conscious awareness of those being subjected to it.

Sternberg pinned the blame on students:

Students, for example, may begin by lifting a few words from materials gathered from the Internet, and gradually progress to sentences, paragraphs, and then major parts of, or even, whole papers.

Yet it was Dean Sternberg himself who lifted major parts of his prior publications and recycled them. Dean Sternberg concluded the article with three prescriptions:

What can one do to discourage ethical drift in one’s colleagues, one’s students, or even oneself? First, an organization needs to recognize and warn its members of the phenomenon of ethical drift. Second, there needs to be a culture of no tolerance for ethical drift. Third, actors need to be warned to be vigilant for ethical drift in themselves and others.

On the surface, Dean Sternberg seemed to advocate a strategy to discourage ethical drift. But given his multiple offenses, his words covertly prescribed the opposite. To encourage ethical drift, follow the example of the three wise monkeys from folklore: “let the eyes not-see, the ears not-hear about, the mouth not-speak about, so the heart may not-find any misconduct.”

Tufts cannot find that Dean Sternberg committed misconduct because his school perforce accepts what its own dean accepts. The situation mirrors Harvard’s, where the president acted on behalf of the entire university when permitting her own use of “duplicative language” without citation. This raises an even broader question: if Tufts implicitly condones a dean’s repeated use of uncited material, what precedent does this set for the future? Will the university also accept the copying of sentences generated by artificial intelligence (AI) software?

Questions about AI at Tufts

Tufts is accepting applications to its new master’s program in AI. The Tufts engineering Dean of Academic Advising, Jennifer Stephan, wrote on her blog: “The future is one in which we all use AI.” During Dean Stephan’s podcast about AI as a major at Tufts, she invited emails from her podcast listeners. So I emailed her:

Professor Stephan,

Email to you at “LanternCollege” did not receive a response. I am a journalist working on a story about ethics in the wake of the Harvard plagiarism scandal.

In your recent podcast about AI, you mentioned your graduate work at CMU and you touched on ethical issues involving AI.

You may be aware of the New York Times lawsuit against Microsoft and OpenAI: “Microsoft and OpenAI acted jointly in the large-scale copying of The Times’s material involved in generating the GPT models programmed to accurately mimic The Times’s content and writers … GPT-4 copied this content and can recite large portions of it verbatim.”

What do you tell students about human or artificial intelligence presenting someone else’s work as original? Is this practice acceptable to you and to Tufts, or do you have policies against it?

My email was read—as seen on email tracking data—but I received no response.

I then asked the same questions of the public relations office at Tufts. One of its staff replied, “I’ll try to get some information” before the end of January, but that didn’t happen. I copied the email to the communications staff at Tufts. They received it but didn’t respond.

I tried again, sending a more expansive email to Provost Caroline Genco, Dean Camille Lizarríbar, Associate Dean Kevin Kraft, and Research Integrity Officer (RIO) Theodore Myatt. They read it but didn’t answer my questions.

So I emailed the Tufts president, who didn’t even bother to read it.

Like Dean Sternberg, these administrators understand how to encourage ethical drift: “let the eyes not-see, the ears not-hear about, the mouth not-speak about, so the heart may not-find any misconduct.”

AI Champions at Tufts: The Dean

In 2019, after joining Tufts, Dean Jennifer Stephan gained notoriety when Dr. Elisabeth Bik reported that Dean Stephan’s advisor Marc Bodson repeatedly copied (20%, 20%, 35%, 20%) from her master’s thesis, then repackaged the papers as a book chapter. Dr. Bik’s sleuthing was recognized by the Einstein Foundation. Despite the exposure, Bodson’s derivative works remain unretracted.

Another online discussion revealed that three-fourths of Stephan’s 1994 IEEE paper “Real-Time Estimation of the Parameters and Fluxes of Induction Motors” was copied from other sources, and that it falsely claimed to present a “new method.” The paper was co-authored by Stephan’s advisor. It “contains text that has been previously published by the author,” just like Dean Sternberg’s papers.

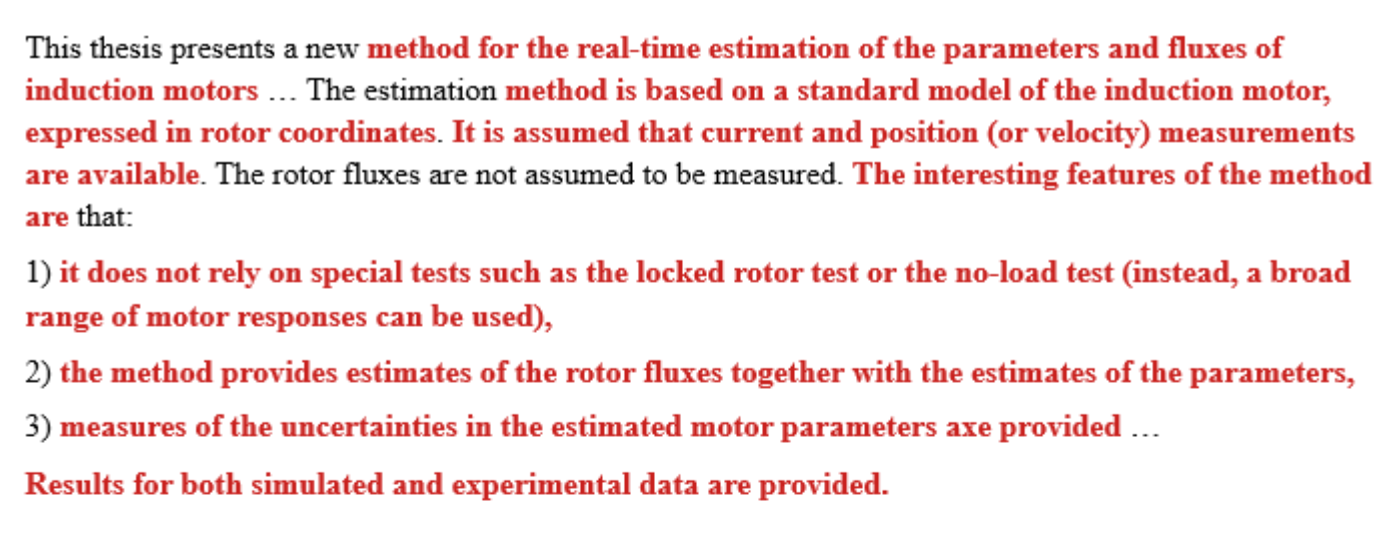

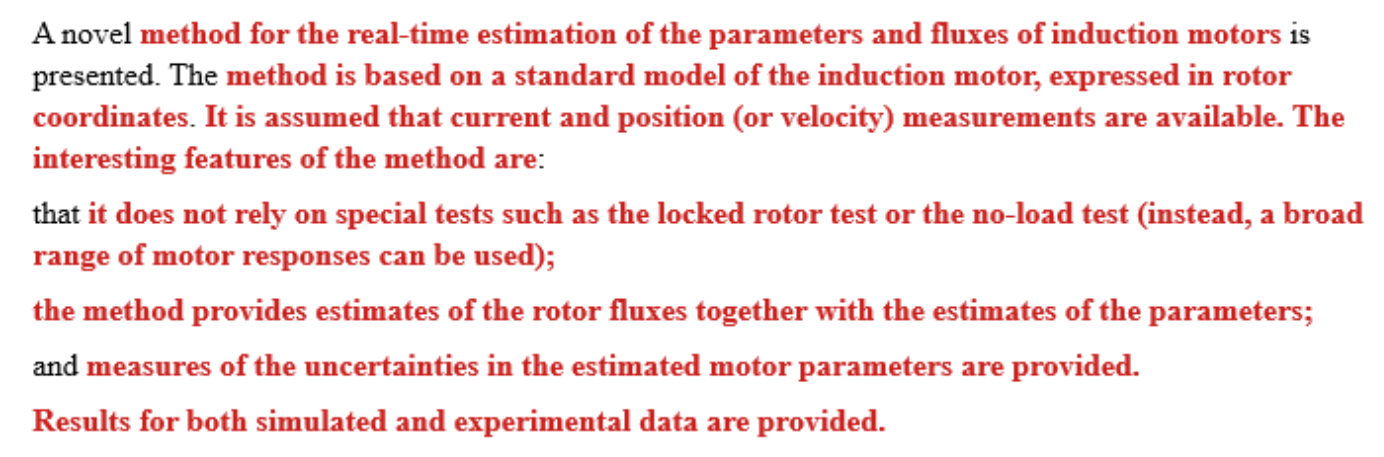

Tufts defines “abetting” to mean “knowingly facilitating” misconduct of others. Did Dean Stephan knowingly facilitate misconduct of her advisor when she listed Bodson as co-author of her October 1992 IEEE paper “Real-time Estimation of the Parameters and Fluxes of Induction Motors” —the same title as her May 1992 master’s thesis? The abstract of her thesis reads:

The abstract of Dean Stephan’s October paper co-authored with her advisor Bodson reads:

It is amazing that the method was “new” in May and still “novel” in October. According to Tufts policy, “fabrication” includes omitting results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record. Did Dean Stephan’s October 1992 IEEE paper accurately represent that the method it described was “novel?” Did Dean Stephan omit explaining that advisor Bodson did not author the work when it was first published in May? Section 8.2.4 of IEEE’s PSPB Operations Manual prohibits verbatim copying without quotation marks and requires authors who copy from themselves to cite their previous work and clearly describe how the new publication differs. IEEE warns that infractions may violate its Code of Ethics which requires the highest standards of integrity and ethical conduct.

It is especially peculiar that the manuscript for their October paper, with advisor Bodson listed as co-author, was submitted to IEEE before the May thesis by advisee Stephan was published. Did she inappropriately take sole credit in her thesis for words that were previously co-authored by her advisor? In 1994, Dean Stephan and her advisor Bodson co-authored yet another work with exactly the same title “Real-time Estimation of the Parameters and Fluxes of Induction Motors.” Was she vulnerable to her advisor’s pressure to let him take credit for her words? Did he exercise academic bullying, from a position of power, of a helpless advisee to gain publication credits for himself?

If it is okay for a professor to take credit for the work of a student assistant or for a student to take credit for work of a professor, it should be okay for a student to take credit for the work of an AI. And if it is okay for a student to facilitate a professor who takes credit for another’s work, it should be okay for an AI to facilitate a student who takes credit for another’s work. Shouldn’t it?

AI Champions at Tufts: The Ethics Professor

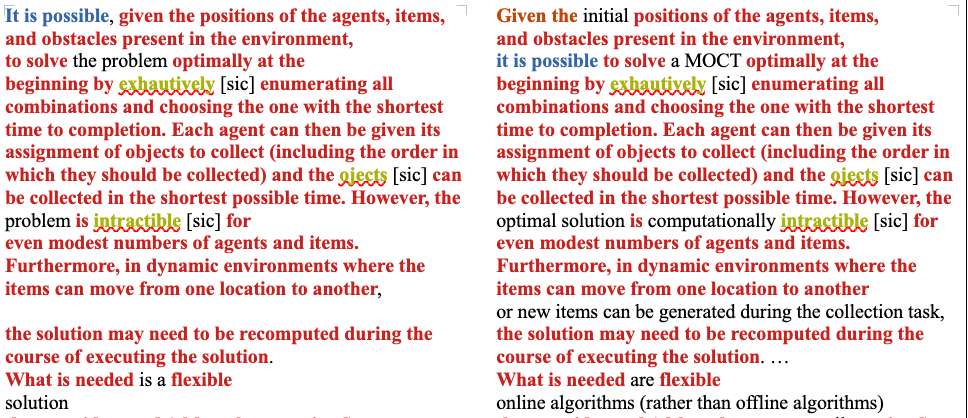

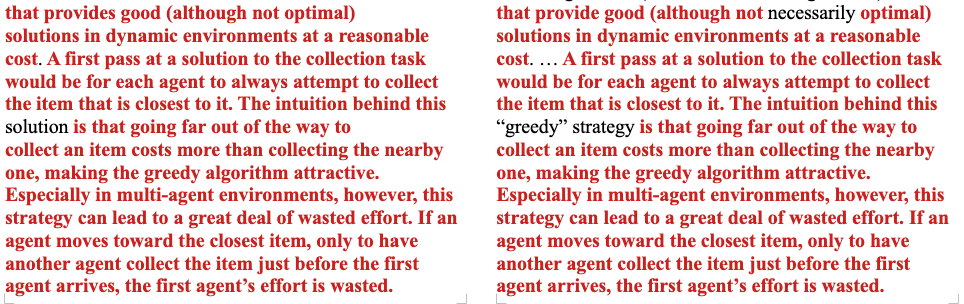

The Tufts AI curriculum includes CS 239 “Ethics for AI.” The ethics course is taught by professor Matthias Scheutz whose 2005 IOS Press paper copied roughly half of his earlier 2003 IEEE paper but neglected to use quotation marks and citations. Ethics professor Scheutz even copied his earlier misspellings “exhautively,” “ojects,” and “intractible.” Excerpts from his 2003 paper (left) and section 2.1 of his 2005 paper (right) are shown below:

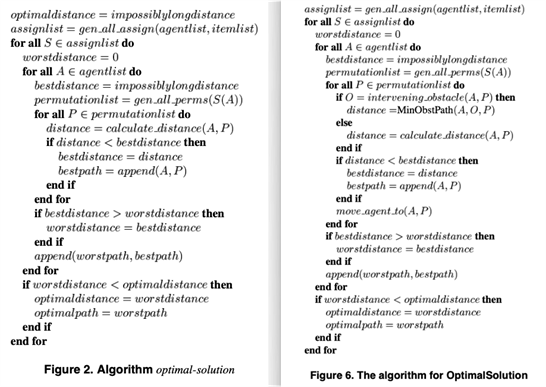

In addition to copying section 2.1, ethics professor Scheutz copied from his earlier 2003 IEEE paper to produce section 3, section 4, section 5.1, and section 5.3 of his 2005 IOP, including the “optimal solution” algorithm.

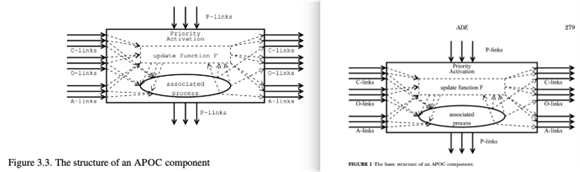

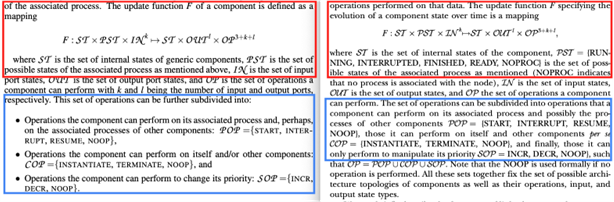

In 2006, ethics professor Scheutz wrote a paper that copied from the 2004 dissertation “APOC and ADE” copyrighted by his doctoral advisee Virgil Andronache. The terms “APOC” and “ADE” refer to an AI framework and the software based on it. Andronache received a PhD for his work on APOC and ADE. If APOC and ADE were the work of professor Scheutz, then why did his student receive the PhD? However, professor Scheutz’s sole-authored 2006 paper begins: “In this paper we present the agent architecture development environment (ADE) … based on a universal agent architecture framework called APOC.” Professor Scheutz did not list his student as a co-author and did not cite his student’s dissertation (shown below left) in the 2006 paper (below right).

If it is okay for a professor to take credit for the work of a research assistant, it should be okay for a student to take credit for the work of an AI assistant. Shouldn’t it?

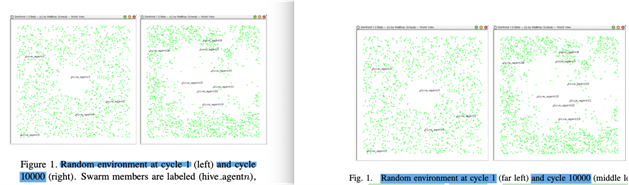

In 2009, ethics professor Scheutz co-authored a paper that copied approximately 60% of their earlier 2005 paper without quotation marks and citations. The 2009 version added five self-citations into the list of references but neglected to include the 2005 paper from which he copied text and figures. This pair of papers was discussed on PubPeer, showing side-by-side examples of duplication, including duplicated figures.

Students in the Tufts AI program should enjoy the same allowances as their faculty. If it is ethical for faculty to receive credit for the words of their students and co-authors, it should be ethical for students to receive credit for the words of their AI. And if such acceptance seems to represent an “ethical drift,” that drift already took place at least twenty years ago, as explained above by Tufts Dean Sternberg.

Embracing AI and Overcoming the Perfectionist Dreams of Abstinence

Tufts has a unique opportunity to exhibit leadership and climb higher in the rankings because other universities are taking the wrong side of the AI-plagiarism issue. In January 2025, the University of Minnesota expelled doctoral student Haishan Yang. According to Yang’s federal lawsuit against the university, the university “generated a ChatGPT answer, edited it at least ten times to make it more similar” to Yang’s exam answers “and used it as evidence” against Yang, even though the AI tool GPTZero “classified Plaintiff’s full exam as human-generated.” Minnesota is failing to take advantage of ethical drift. Minnesota is relying on a worn-out tradition where administrators listen to complaints, look at written work, speak against using AI assistance, and make findings of misconduct.

Tufts, on the other hand, can provide value to its stakeholders by accepting and embracing the use of AI, just as it has accepted various practices of its faculty and administrators. By using AI, Tufts faculty can increase their publication counts by a factor of two—maybe a factor of a hundred! Tufts can parlay this increased productivity into more publicly funded grants to support more students to write even more papers.

The old days of plagiarism-abstinence are a relic of the baby-boomer generation. Students now use all manner of assistive devices to help them succeed, yet administrators are reluctant to counsel students in how best to exploit AI to perform their work. Administrators are under pressure to recommend that students abstain from using AI, but as Tufts Dean Jennifer Stephan argued:

abstinence programs withhold information about less than perfectionist goals … the perfectionist model limits what counselors can say. … these norms create ethical dilemmas. Unfortunately, the perfectionist model limits information in ways that prevent youth from making informed choices about their options. (“Perfectionist dreams and hidden stratification: Is perfection the enemy of the good?” Frontiers in sociology of education. 2011: 181-203.)

The AI ship has already sailed. The AI horse has left the barn. Tufts, like its neighbor Harvard, can lead the way for students, faculty, and administrators nationwide by openly declaring in its policy that it has rejected plagiarism-abstinence and the perfectionist movement it represents. The new and improved AI-inclusive language at Tufts could be modeled along the following lines:

Plagiarism will never be found to be misconduct here. Self-plagiarism is okay. You can abet plagiarism and self-plagiarism. These are accepted practices in our community. There is no need to cite your sources or enclose passages in quotation marks when you copy them. Let others do the writing for you.

Let AI write your papers. Train an AI so it can help your classmate. All of this is fine. Once upon a time, plagiarism abstinence was required, but not anymore. Not on our watch. Perfectionist goals will not serve you well as you enter the workforce. Taking credit for the work of others makes good business sense. AI can help you with that.

This one weird trick increases your productivity and your credentials. It will help you advance in your career. If someone reports that an AI did your work for you, we will not-listen; we will not-look, we will not-reply. And we certainly will not-find it to be misconduct.

Image: Tufts University by Pete Jelliffe on Flickr