Progressive bureaucrats, student activism, eager donors, peer pressure: higher education institutions have an array of internal and external drives for promoting race, gender, and other leftist ideologies, but a powerful factor lies with mandates from accreditors to comply with diversity standards for institutional culture, staff and faculty hiring, student outcomes, and other relevant areas.

In light of the Trump Administration’s unrelenting efforts to purge racial discrimination from higher education, some college accreditors are taking steps to decrease their entanglements with “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI). For instance, the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) has dropped DEI from its accreditation criteria and supporting documents. Similarly, the American Bar Association (ABA) temporarily suspended its DEI enforcement for law schools.

However, most accrediting agencies are still staunch supporters of DEI and racial preferences, having baked the ideological edict into strategic goals, organizational standards, mission statements, policy positions, etc. Following the Dear Colleague Letter from the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights (OCR) sent on February 14, 2025, the Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions (C-RAC), which represents seven federally-recognized accreditors, issued a defiant response. In it, C-RAC accuses the OCR of interpreting the Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (SFFA) decision too broadly. Specifically, C-RAC argues that the ban on racial preferences should only apply to admissions decisions, not “hiring, promotion, compensation, financial aid, scholarships, prizes, administrative support, discipline, housing, graduation ceremonies, and all other aspects of student, academic, and campus life.”

“Encouraging DEI” appears in the Code of Good Practice for the Association of Specialized and Professional Accreditors. The only organization representing specialized and professional accreditors had a session on legal strategies to carry on DEI in accreditation at its Fall 2024 Conference.

For the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE), DEI is “Guiding Principle 3,” dictating that member institutions should “address disparate impacts on an increasingly diverse student population.” “With equity at its core,” the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College & University Commission (WSCUC) recently reaffirmed its institution-wide commitments to the dogma. After a failed attempt to dial down DEI, WSCUC now continues to endorse that equity and inclusion are embedded in its strategic goals and infused throughout its standards for accreditation. The goal of equitable student outcomes is also shared by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU) in its standards, the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (ACCJC) in its 2030 Strategic Plan, and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC) in its 2023-2028 Strategic Plan.

Unchecked, accrediting agencies only pretend to go along with reform.

In 2021, the Higher Learning Commission, the MSCHE, and the ACCJC joined a slew of associations and unions in a statement opposing state legislative bans on race essentialism as attacks on academic freedom. In 2024, NWCCU President penned a letter to its members, elaborating on “the compelling rationale” for DEI. More than voluntary self-redress is needed to systematically remove the overshadowing pressure on colleges and universities to engage in racial preferences from their accreditors.

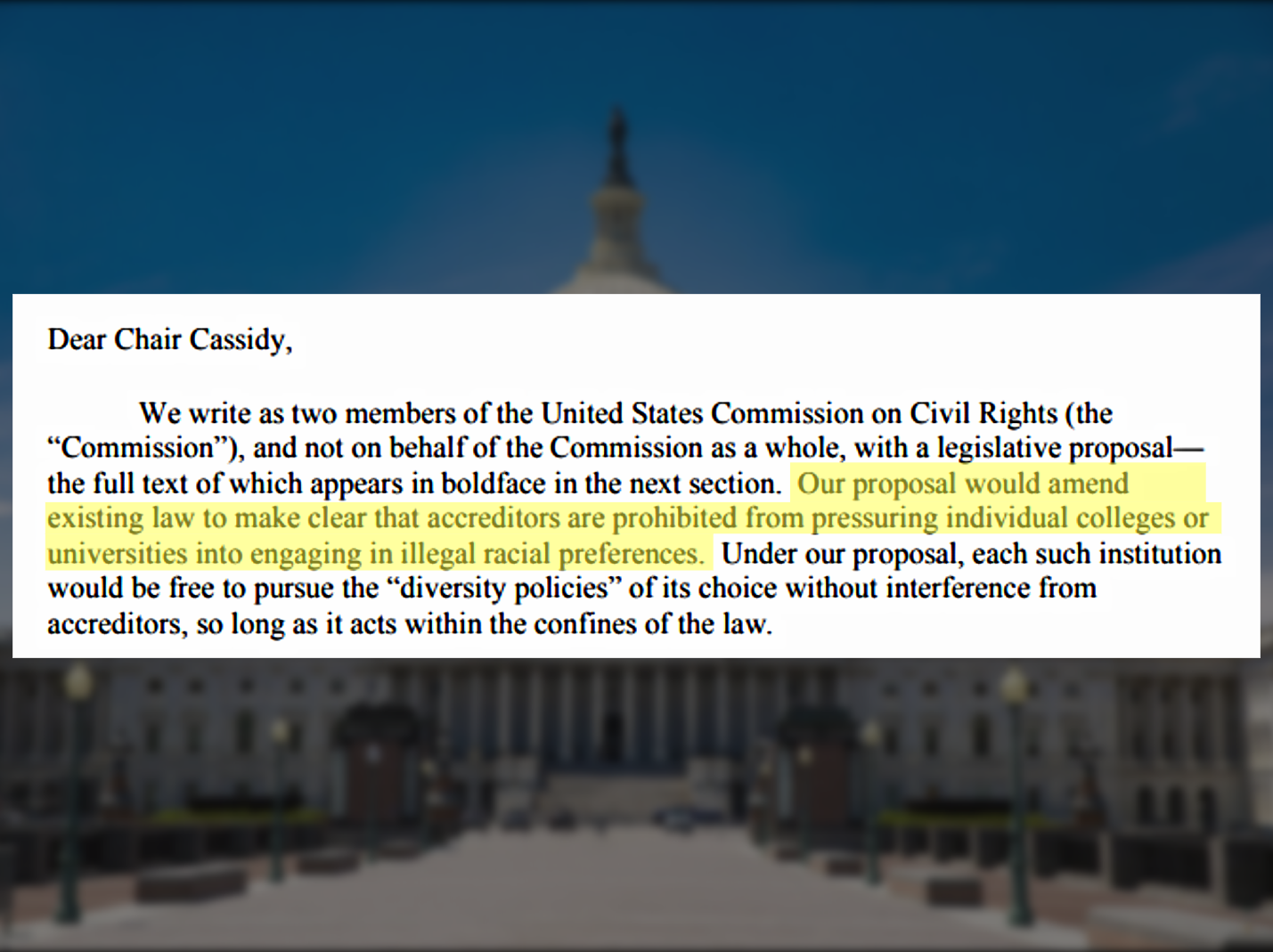

To this end, U.S. Civil Rights Commissioners Peter Kirsanow and Gail Heriot are proposing a simple legislative reform aimed at prohibiting accrediting agencies from mandating schools to implement race-based diversity requirements. Their plan, outlined in a compelling letter to U.S. Senator Bill Cassidy, who chairs the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, builds upon the notion that accreditors’ “demands for diversity can only be satisfied at many schools through preferential treatment based on race (and hence by violating the law).” Therefore, the two commissioners ask that Congress amend 20 U.S. Code § 1099 to include a new subsection:

No accrediting agency or association may be determined to be a reliable authority as to the quality of education or training offered for the purposes of this chapter or for other federal purposes, if the accrediting agency or association imposes requirements concerning student body, faculty or staff diversity on the basis of race, sex, or national origin; establishes standards for student body, faculty or staff diversity on the basis of race, sex, or national origin; conducts investigations into student body, faculty or staff diversity on the basis of race, sex, or national origin; or makes recommendations regarding student body, faculty or staff diversity on the basis of race, sex, or national origin. An accrediting agency or association may only be determined to be a reliable authority as to the quality of education or training offered for the purposes of this chapter or for other federal purposes if it permits each and every college and university that it accredits (and each and every component or subpart of the colleges and universities that it accredits) to adopt any lawful policy on student body, faculty or staff diversity on the basis of race, sex, or national origin notwithstanding the particular mission of the particular college or university (or component or subpart thereof).

Unlike their left-leaning counterparts, including a group of law professors who insist that DEI programs are indiscriminately lawful, Kirsanow and Heriot used their letter to demonstrate the rationale for such a reform with empirical evidence. They argue that “[a]ccreditors have long been strong-arming colleges and universities into greater levels of racial preferences.” For instance, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), the accreditor of public medical schools, had cited half of the 16 schools surveyed in public records requests “for being insufficiently diverse.” As early as 1988, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) had adopted diversity standards for the colleges and universities it accredited. Since 1990, WASC has pressured schools, including the Rand Graduate School of Policy Studies, Thomas Aquinas College, Caltech, Stanford, University of Southern California, and UC Berkeley, into promulgating official “diversity statements.”

Throughout the 2000s, the American Bar Association (ABA) threatened to revoke George Mason University School of Law’s accreditation for its lack of racial diversity and issued multiple action letters demanding compliance with ABA’s diversity standards. In one of these action letters, ABA’s Accreditation Committee complained that the school did “not engage in any significant preferential affirmative action program.”

As such, accreditors have long track records of engineering strong incentives for racial preferences, targeting schools that depend on them for recognition. Surely, as Commissioners Kirsanow and Heriot have noted,

[A]ccreditors are [not] the only source of pressure on colleges and universities to ignore the Supreme Court’s decision in SFFA. Rather, complex webs of state and federal oversight and grant-making authority combined with outside funding sources, all of which insist on “diversity,” all contribute to the difficulty. Nevertheless, accreditors are perhaps the most powerful of these. If an institution of higher learning is not accredited, its very existence is jeopardized. If accreditor pressure were removed, we believe that the level of compliance with the law would increase significantly.

Observers and reformers of higher education should support this sensible legislative proposal to remove the ideology of diversity and racial preferences from the accreditation process.

Cover designed by Jared Gould using an image of the U.S. Capitol Building by Senate Democrats on Wikimedia Commons and screenshot of letter from the United States Commission on Civil Rights to Senator Bill Cassidy, written by Commissioners Peter Kirsanow and Gail Heriot.

A basic problem these accreditors have grown is that their diversity is only skin-deep; their lack of ideological diversity is appalling, and has much to do with why so many Americans now want the higher education establishment to contract to perhaps half its current size, since so many of its expensive offerings return negatively on their investment.

But rather than diversity, an obvious institutional advantage, other things being equal, the big problem with DEI is in the “equity”, a contested term. In its basic meaning of “fairness”, it is unobjectionable; but in addition to the obvious unfairness of treating equals unequally (traditional race-based discrimination, for example), such unfairness includes treating unequals equally, which was the basis for Harvard and the University of North Carolina losing the Students for Fair Admissions case, a blindness to which shockingly afflicts American leftists, whose definition of “progress” is not shared by most Americans.

Reality is that it is going to have to shrink by about a third because we simply don’t have the bodies to fill the seats.

When the Baby Boomers aged out of the traditional 18-21 year old college cadre, institutions filled their seats with older women who either hadn’t gone to college or had dropped out to start their families. That’s not going to happen this time because the Millennial women already have their degrees.

Every college in the country expanded in the ’00s when the Millennials arrived, and now there is going to have to be shrink. Gen Z are the children of Gen X, and Gen X are the children of the very small generation born during the Depression and WWII. By contrast the Baby Boomers were the parents of the Millennials — we’ve had alternating big and small generations all the way back to the Civil War.

And then people stopped having children when the economy tanked in 2008.

And this is the demographic issue confronting higher education –there are about a third too many seats to fill.

You do not know what you are talking about – What you completely ignore is how often ‘diversity’ includes to the poor white (rual) farmer kid, or even the rich kid! If you look deeper than your own fear to compete on equal ground ( for you and/or your children) you will find that the goal of most University Admissions is to give the student body a wide swath of exposure. Furthermore, you and your parents before you specifically benefited from the inheritance of racist, preferential educational, judical and economic practices that still exist today.

basis of race, sex, or national origin

I would add :sexual orientation or identity” and the reason for this involves the psychology and counseling program accreditors.

It started with Jennifer Keeton 15 years ago — https://adflegal.org/case/keeton-v-anderson-wiley/#case-details — and now extends to transgender as well.