“Like a mutating virus, racism shape-shifts in order to stay alive; when its explicit expression becomes taboo, it hides in coded language.” — Kathy Waldman

In 2024, several states, including Idaho, Utah, Iowa, North Dakota, and Arizona, passed laws prohibiting public universities from using “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) statements as part of the hiring process. At least five other states have proposed similar legislation, and more are expected in the coming year. Although opposition to DEI in higher education has many causes, resistance to DEI statements themselves largely stems from how the statements are sometimes used as ideological litmus tests that prioritize political conformity and homogeneity over intellectual diversity and merit-based hiring while simultaneously curtailing or outright eliminating consideration of qualified applicants who do not unequivocally conform to the prescribed approach to social justice. However well-intentioned, the statements function more as what one writer described as “compelled speech” than as mechanisms for choosing the best candidates while undermining academic freedom. And that is a problem, not just for higher education but for prospective students and faculty as well.

Determined to realize my own lifelong professional aspiration of getting a tenure-track job, I probably applied for 200 positions before finally giving up. I can’t remember how many times I advanced to the semi-finalist stage of the process, but I do recall the one and only time I was one of three finalists for a good job at a small liberal arts college in Idaho.

That was about 20 years ago, but I remember the experience vividly, I think, because of the event’s singularity and because of the difficult pleasure of the event itself—that is, interviewing for three straight days and coming so close to getting the job. Had things gone differently, I would likely now be enjoying all the privileges and trappings of being a full, tenured professor and working in the field I was trained in. As Hemingway once said, it’s pretty to think so.

[RELATED: A Crisis Averted is Not a Crisis Solved: DEI Reforms Face Resistance]

Given this dearth of opportunities, I’ve asked myself some tough questions over the years. Should I just accept my situation—my ceiling—and give up my search for a better job? Why aren’t I getting interviews? What am I doing wrong?

I realize there are countless answers to why I’m not getting interviews—some within my control, most not—but that’s no reason to avoid asking the question. Honest answers could help appraise what one truly has to offer and better understand the forces shaping the job market. Yet, before asking, “Why not me?” it might be wise to first consider what—or who—“I” means.

Until a few years ago, I thought “I” simply referred to the sum of my qualifications, established through a letter of interest, a CV, letters of recommendation, and occasionally a teaching statement. Back then, I worked hard to ensure these documents accurately portrayed me without raising red flags. The only real risk of misstep lay in the teaching philosophy, where the exploratory tone might tempt me to reveal more than was prudent. Otherwise, the process felt straightforward—devoid of the ideological landmines embedded in today’s standards. All I needed was to demonstrate my qualifications through clear, largely apolitical conventions.

The general understanding back in those days was that one’s chances of getting an interview were based on one’s qualifications, which, in contrast to the rubrics used today, are fairly easy to identify and assess. This is not to say that one’s person—or, in the parlance of the moment, one’s identity—wouldn’t become important at some point, but at that early stage of the process, all that mattered were one’s professional credentials. The process was relatively straightforward, more-or-less transparent, explicit, and, perhaps most importantly, I believed, gave me a chance.

I probably don’t need to tell this to people on the job market, but for those of us who fail in landing a desirable position right out of graduate school, maintaining a healthy belief in the future and one’s professional viability is crucial. In fact, I remember times when, after not advancing in a job search, I followed up with the committee chair and asked how I could improve my chances of being considered for future positions. Sometimes, the chair encouraged me to do more service work, to publish more widely, or to present at conferences—things that, while involving various levels of difficulty, were still possible. However imperfect, under that paradigm, there were clear steps to grow professionally and thereby improve my chances of getting interviews and possibly, in the next round, winning a job.

In the context of today’s job ads emphasizing “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) and treating identity as a primary basis for candidacy, “I” now often refers to racial and gender identity above all else. This shift renders follow-up conversations with search committee chairs ineffective for candidates who do not represent a target identity. For those individuals, barring drastic steps like becoming an identity imposter, rejection often signals the end of the line—troubling given all the traits that define a person beyond their appearance. While DEI—or diversity—statements, often required in job applications, aim to support efforts to recruit and retain diverse faculty, students, and staff, some practices may not achieve the goal of true diversity—defined as welcoming individuals who look and think differently. Paradoxically, these statements may discourage or preemptively exclude highly qualified candidates, undermining the broader intent of fostering a truly inclusive workplace.

[RELATED: DEI’s Silence on Religious Diversity]

Thus, job ads that prioritize DEI statements may yield exclusive results insofar as they privilege some forms of diversity to exclude others. I’ve read hundreds of job ads and talked to dozens of people about their own experiences with the job search. And I’ve never met anyone who, upon finding DEI language in a job ad, including requests for a DEI statement, thought that it included white people. One academic I interviewed for this essay—a white senior lecturer with graduate degrees from two, top five programs in the country—told me that any time he comes across a job ad that prioritizes DEI and uses “coded language,” he doesn’t even bother applying. Anyone who extols the importance of DEI should, at the very least, consider this alarming.

Abigail Thompson, a professor and chair of the mathematics department at UC Davis, would no doubt agree. A few years ago, after becoming “increasingly uneasy with the use of DEI statements in faculty hiring,” she wrote an oped calling out university administrators for implementing what basically amounts to a leftist ideological litmus test for hiring. “No longer will faculty hiring committees use their own judgment about how best to create a diverse and inclusive environment in their fields,” she writes. “Instead, each candidate’s commitment to diversity will be assigned points. To score well, candidates must subscribe to a particular political ideology, one based on treating people not as unique individuals but as representatives of their gender and ethnic identities.”

Shortly after Professor Thompson’s piece appeared in the Wall Street Journal, emeritus professor of Biology Jerry Coyne published a detailed—and deservedly unflattering—analysis of UC Berkeley’s use of diversity statements to eliminate candidates, particularly white males, who, in one search “were reduced from about 60% of the candidates to none of the interviewees.” I wonder how many other graduates and job applicants would feel demoralized and hopeless after learning about what’s happening in the UC system and other universities nationwide. This should be of great concern to everyone in higher education, but the parties most responsible for weighing the virtues of DEI statements should take special notice.

Clearly, identity will continue to play an important role in hiring. But can a hiring process that gives precedence to identity above all else ever truly reflect the values of DEI? What if, by requiring DEI statements, universities have gone too far? These are tough questions, but any honest discussion of how best to achieve a diverse workplace will make every effort to address them.

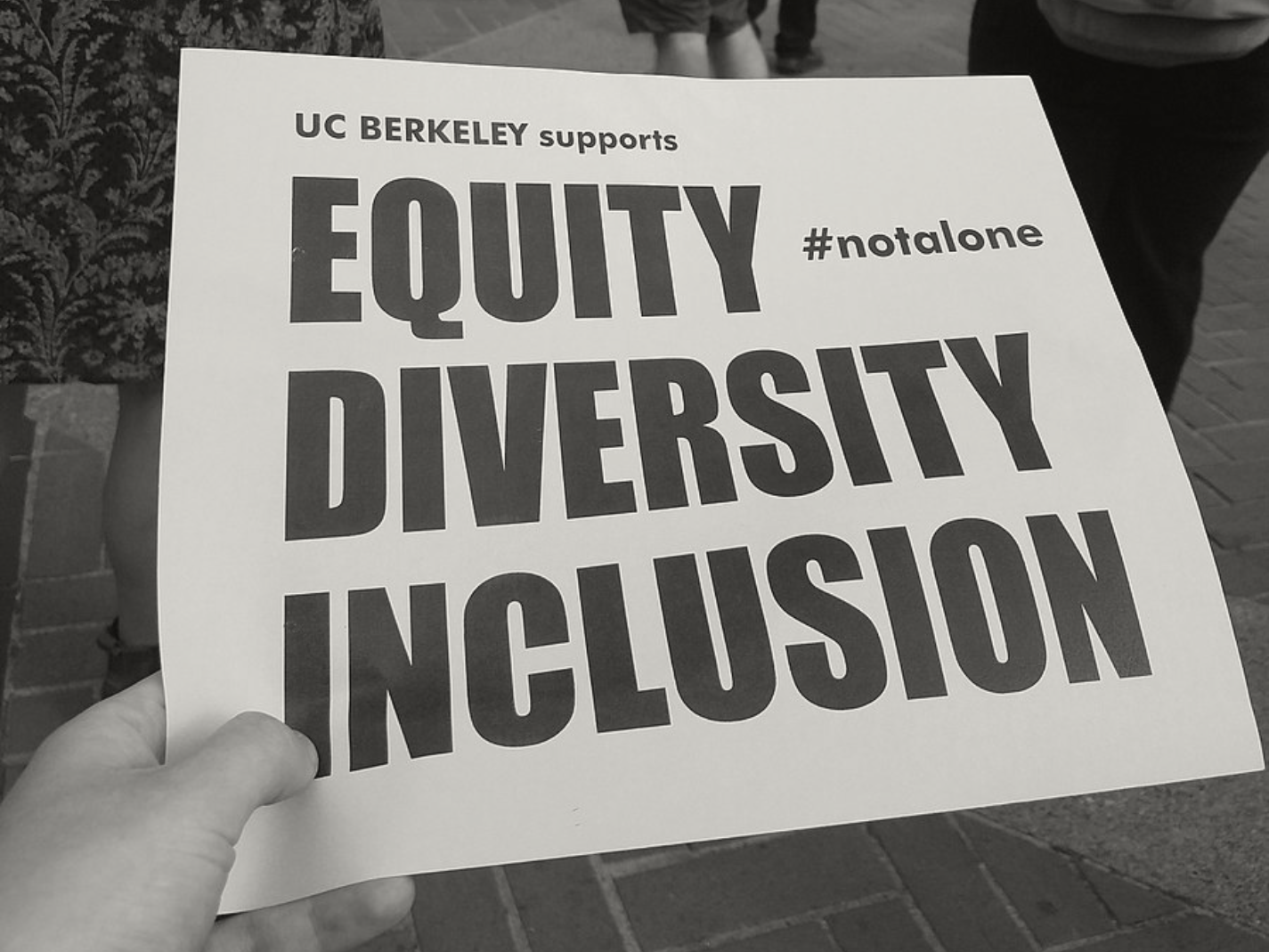

Image of DEI pamphlet at UC Berkley by Quinn Dombrowski on Wikimedia Commons

I like how the author of this attributes this more to DEI policies than to the possibility that of other candidates being better suited or just a better competitive job market. There is no reflection on whether the other finalist had more publications, better teaching evals, or stronger recommendations.

Now– Consider this. Academia, especially for tenure track positions are extremely competitive. They are judged on publications records, teaching exp, networking and fit. IIRC its 1 to 3 percent of applicants that get offers. Its normal to apply to hundreds of jobs and not get hired, even if qualified.

The author uses DEI as a scapegoat. Its easier for them to blame DEI than to accept that other candidates are stronger and that the job market in academia is notoriously brutal.

1. DEI doesn’t mean hiring unqualified people. It means broadening the pool and considering a wider range of experiences, not just white kids.

2. The best candidate is still suppose to get the job.

Author also claims that identity is prioritized over quals but offers no evidence that less qualified candidates were chosen.

Its pure logical fallacy. Just because diverse candidates were chosen, doesn’t mean they were less qualified.

DEI didn’t stop him from being hired. A more competitive candidate did.

Blame the system, right?

Patti above perfectly illustrates the purpose of DEI and how it works. Few women graduate from physics programs–in part because they don’t have role models and institutional encouragement. (American girls tend to excel and then drop out of “interest” in science in droves starting at about fifth or sixth grade.) So DEI is about, when you have *at least equally qualified* female/Black/disabled/other underrepresented candidates, you consider hiring them over the usual able-bodied white male candidates (who still hold like 90% of major decision making positions), because we’ve needed more voices at the table. Women physicists (mathematicians, engineers, medical researchers, computer scientists, etc., etc.) belong, Black physicists belong, disabled physicists belong… and women/Blacks, etc. need to see themselves represented by professionals in their potential fields, and the het white males need to learn their perspectives. But DEI is NOT about demographics *over merit.

The 14th Amendment promises Equal Protection under the Law. I should not have to write an essay describing my devotion to “Diversity” in order to teach science or conduct research at a university. There is nothing more illiberal than requiring an essay that is supposed to lean favorably toward one side of the political spectrum, such as this requirement.

None of this is new. 25 years ago when I was program lead for our department we were looking for a new full time professor. One candidate in the final interviews had been taken out of the pool twice by the hiring committee for insufficient credentials and evidence of area expertise. After being put back in the pool twice by senior administration he presented himself in the final interview. Afterwards I turned to the Vice President for academic affairs (at that time we did not yet have a provost) and said that the candidate did not have sufficient credentials to even graduate from our program. The VP responded, “Sometimes credentials aren’t the important thing.” They got their hire. He lasted one year. And the school lost a discrimination law suit.

Thank you for addressing this concern. I have applied to 24 rhetoric and writing positions in the last two months as I finish my dissertation – I creatively, generously, and constructively disagreed with the excesses and limitations (and demonstrable flaws) of the social justice paradigm during my phd from 2020 til now. But it has cost me my colleagues, my reputation, sanity, and confidence. Despite having taught almost 70 sections of composition, technical writing, and ESL writing with excellent peer reviews and student survey responses since 2015, in addition to directing a writing center full-time, obtaining 2 MA degrees in that time and now my PhD, my identity remains a glaring problem and professional liability. Do I check the UC and CSU application boxes that indicate I am white (non-hispanic), male, cisgender, and heterosexual? Or do I decline to state on all aspects?

I’m sorry to hear this. I wonder what a longitudinal study would reveal regarding hiring practices in your field. Would it be like Berkeley’s? As a side note, the senior lecturer I mentioned in the piece left academia and is now writing for a children’s hospital. He’s getting paid quite well, but he also reports having to make some serious adjustments after being part of the academy for almost two decades. Like you, he has very impressive credentials and experience. I guess I was lucky insofar as I got a job that still allows me to teach and write and do the things I love. But it is also a fact that I would never get this job now. Not a chance. So perhaps gratitude is the only appropriate response at this point. I don’t know. Regarding your question, you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t, in which case refusing to buy in and declining to answer may be the best choice. But what do I know? Not much, it turns out, especially when it comes to who gets interviews and who does not. Hang in there.

It’s upper-middle class white women who have really benefited from affirmative retribution, thirty years ago it was males who were excluded.

And now there is great concern about white males not going to college anymore — I can’t imagine why they wouldn’t want to…

Women still benefit from DEI. A couple of years ago a California University (Univ. of Cal at SD?) had a tenure-track assistant professor position opening in the Physics Department. The top 5 candidates were invited for on-campus interviews. Surprise, surprise, surprise. All 5 of these candidates were female. (As a side note, only one out of eight PhD students in physics are female.) Must be a coincidence. Yeah, that must be it.