For unto us a child is born. Unto us a son is given. — Isaiah 9:6

On Christmas, we celebrate a phenomenon theologians call the incarnation. The birth of Jesus Christ was the trans-dimensional irruption of the Son of God into our world from the heavenly realm. Both the Old and New Testaments give witness to Jesus’ miraculous conception by the Holy Spirit to a young Jewish virgin named Mary. As if this weren’t strange enough, the late Reverend Dr. Timothy Keller adds to the incredulity, reminding us that “Jesus was the only son given, and the only son born older than his parents.”

Science doesn’t always have the best answers for extraordinary phenomena. Writing in “Has Science Refuted Miracles and the Supernatural?” one of the essays in the Comprehensive Guide to Science and Faith, Richard G. Howe explains, “While it might be understandable that a scientist would balk at the idea that there are aspects of reality that lie beyond the purview of science, I submit that any scientist who denies this is tragically failing to see what is staring him right in the face.”

So, what evidence is there that the birthday we celebrate every year on December 25 was an actual historical event and not some myth or legend conjured up in the minds of the Jewish authors of the Gospels?

[RELATED: The Evolution of Christmas]

Read any of the genealogies in the Old Testament, and it becomes immediately apparent that only men’s names were recorded: “These are the generations of … Adam, Noah, Shem, Terah, Isaac,” and so on. Patriarchy was the norm of Jewish society. What was true in the Old Testament was also true in the New Testament—except for the genealogy of Jesus recorded in Matthew’s Gospel.

Matthew included five women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and, of course, Mary, the mother of Jesus. With the lone exception of Mary, the other four were either of questionable moral character, not Jewish, or both.

In Genesis chapter 38, we learn that Tamar masqueraded as a Canaanite prostitute to trick her father-in-law, Judah, into impregnating her to further Israel’s chosen dynasty.

Joshua chapter 2 records the story of Rahab, a Canaanite harlot living in Jericho who was instrumental in hiding Jewish spies.

In the Book of Ruth, we learn that Ruth was from Moab—the sworn enemies of Israel. It is believed that her father was King Eglon. We read about his scatological demise in the Book of Judges, chapter 3, which details the gory account of his assassination at the hands of Ehud, one of Israel’s judges, who stabbed Eglon while he was sitting on the toilet moving his bowels—a story every young boy loves to hear read in Sunday school!

Bathsheba was the wife of Uriah the Hittite. It was with David that she fathered an illegitimate child while her husband was away at war.

You can’t make this stuff up. And I mean that seriously. It isn’t fiction.

No Jewish author writing during the first century would ever have included women in general, especially not these women, in a genealogy of an important person, no less the heir of Israel’s royal throne, unless it were true and the author was recording historical fact.

The genre of the fictional narrative was still over a millennium away, not appearing until the Middle Ages. In the Invention of Fiction, Laura Ashe writes, “Fiction was invented in England in the 12th century; we might pinpoint a few years around the 1150s as the crucial moment. Fiction gives an account of something unverifiable and which does not ask to be believed, only to be thought about; it is a contract between author and reader.”[1]

The Gospels, in contrast, give an account of something verifiable. The writers are asking their readers to believe. “For we did not follow cunningly devised fables,” wrote the Apostle Peter, “but were eye witnesses of his majesty.”

But Matthew’s genealogy is more than mere first-century journalistic excellence. While a literary analysis supporting the authority of the Scriptures is academically interesting, it misses the deeper, spiritual meaning of the Gospel narrative.

[RELATED: Trip Down Memory Lane: Christmas with David Randall]

As academics, we are too often focused on, well, academics, and we miss the deeper, more practical and spiritual aspects of Scripture when we analyze it strictly in accordance with its literary genre or from a critical-historical perspective.

The Bible is its own witness. The prophecies recorded in Matthew’s first two chapters describing the birth of the Christ child are direct quotations from Old Testament prophets: Matthew 1:22 is taken from Isaiah 7:14, Matthew 2:6, is from Micah 5:2,4, Matthew 2:15, is from Hosea 11:1, and Matthew 2:18 is from Jeremiah 31:15. The oracles recorded in these Old Testament books are Ancient Near East documents that need no additional authentication.

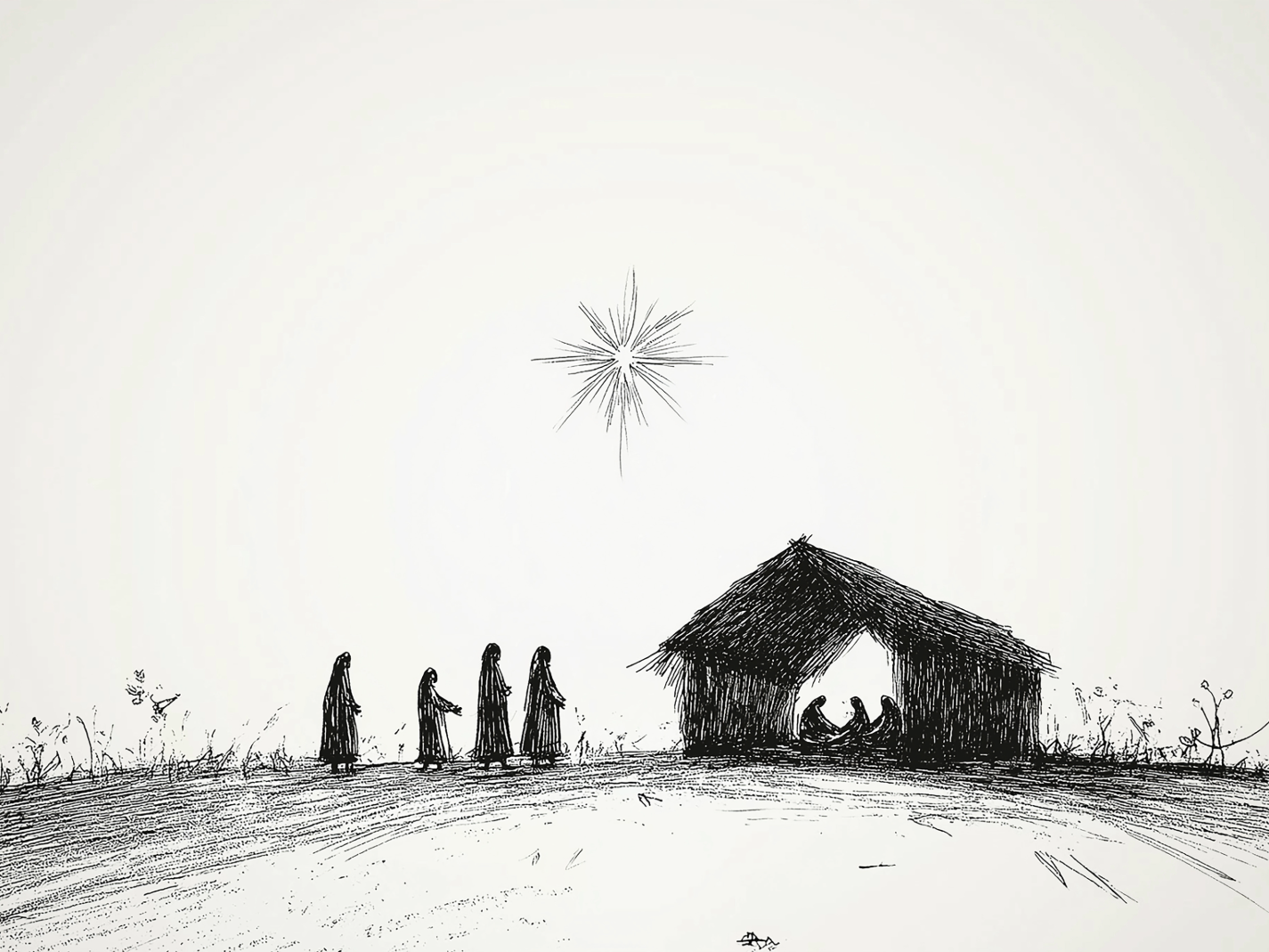

But Matthew wants his readers to see that the real gift of Christmas is God declaring that all are welcome at Bethlehem’s stable, not just the rough Hebrew shepherds who were watching their flocks by night or the wealthy wise men who traveled from afar to bring the Christ child gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh, but all men, all women, and foreigners, too.

The gift of Christmas is an all-inclusive offer to everyone willing to believe its message: “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16).

Merry Christmas, everybody!

[1] Laura Ashe, “The Medieval Invention of Fiction,” History Today, February 13, 2018. https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/medieval-invention-fiction

Image by Uladzislau — Adobe Stock — Asset ID#: 932310694

Well done.