I cannot imagine such an arrangement on a secular campus occurring today.

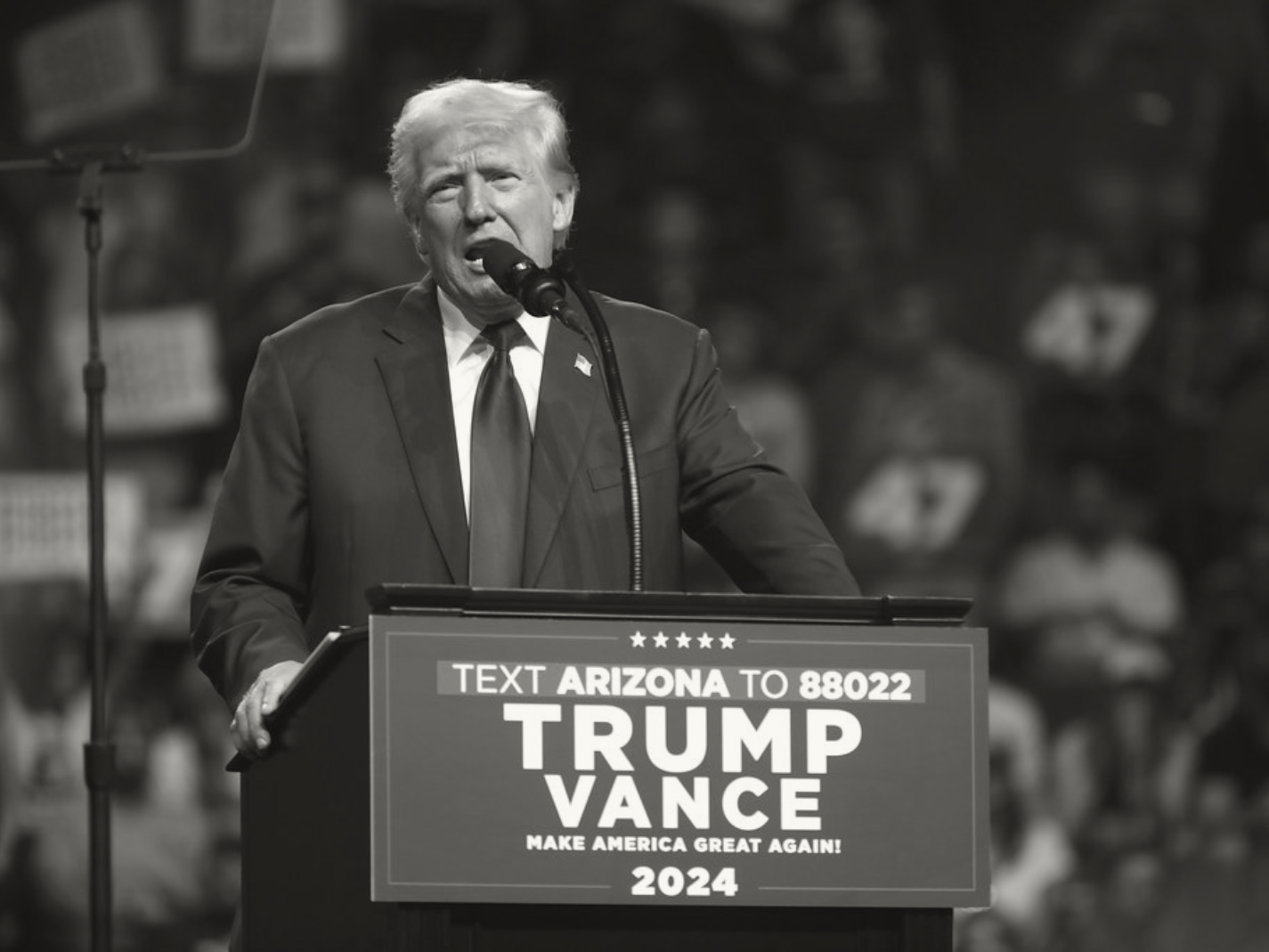

However it plays out, Donald Trump’s plan to exorcise college campuses of woke ideological domination is heartening to those who desire a genuine spirit of intellectual debate on college campuses. The hard left stifles genuine debate since it denies the value of the freedom of speech to those whose ideology it deems “toxic” and “repressive.” Much of this traces to Herbert Marcuse’s essay, “Repressive Tolerance,” published in 1965. My readers will likely need no convincing that the ideas of “an open marketplace of ideas” or “may the best argument win” are not alive and well on most campuses, especially state schools. But it was not always so, and perhaps it can change for the better. Let me tell a story of true tolerance of the liberal sort at a secular university.

At some time in the late 1960s or early 1970s, the University of Oregon (Eugene) set up a program that allowed non-faculty to teach accredited courses at the university—for no pay—if they could receive a faculty sponsor and be approved by an academic department. The program was called SEARCH. Although I taught in this program from 1979-84 and in 1989, I have no idea what the acronym stood for. The concept for this program was not overtly based on conservative principles but emanated from an egalitarian sensibility that community people should be allowed to contribute to the university: “Power to the people!” It was something like an extension of the popular teach-ins of that day. It was probably placed in the category of an “experimental college.”

[RELATED: I Attended Hereticon]

I took a version of this class, called “In the Twilight of Western Thought,” as an undergraduate philosophy major who was getting his sea legs as a thinking Christian at a secular university. After graduating in 1979, I began to work at a Christian Study Center near campus. A friend asked me to co-teach the course I had taken from him. Our course explored the Christian worldview in relation to other worldviews, such as Deism, Naturalism, Nihilism, Existentialism, Eastern Pantheistic Monism, and New Age thought. He later handed the class over to me. Our principal text was a clear, fair, and popular book by James Sire called The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalogue. We supplemented this with sociologist Peter Berger’s little classic, A Rumor of Angels. The class was offered as a 400-level sociology course but counted only as an elective. We had an advocate in Professor Benton Johnson (1928-2024), the head of the Sociology Department. He was not a Christian, but he realized that I was qualified to teach the class and that other viewpoints needed to be presented at the university other than the default secularism. We used to say that he was “a true liberal” in that sense.

Nearly every term, someone would claim that our class should not be taught because it violated the separation of church and state or because it involved proselytizing. This came to a head one year when the president of the law school was assigned to investigate the legitimacy of the course. He attended one of my lectures and needed me to meet with him to defend the class.

[RELATED: America Was Not Founded on Separation Between Church and State]

I argued that we did not proselytize but merely presented the Christian worldview in relation to other worldviews. We were not a church, and the First Amendment does not forbid Christian views from influencing society so long as there is no coercion. I added that no student would be penalized for not holding the Christian worldview and that Christians who did bad work would not be favored. I left the meeting satisfied that I had given the best case I could and that if the class were shut down, I would have nothing to regret. Much prayer went into this as well.

The class survived this scrutiny, and I taught it for another year or two. When I returned to the University of Oregon for my Ph.D. in 1989, I taught another iteration of the class, this time emphasizing the New Age worldview in relation to Evangelicalism, using my own book, Unmasking the New Age and James Davison Hunter’s early work, American Evangelicalism. The SEARCH program was discontinued sometime after this.

I cannot imagine such an arrangement on a secular campus occurring today. However, there seems to be nothing intrinsically wrong with opening the secular university to “viewpoint diversity,” given the stress on ethnic diversity and given the classical liberal idea that all pertinent perspectives deserve a right to be heard in “the marketplace of ideas”—such that the best argument has a chance to win. Perhaps Donald Trump’s plans to revamp higher education will leave room for some new version of my class from many years ago. I hope so. And please sign me up if it happens.

Image of Donald Trump Sign on Flickr

I very much enjoyed the article. My main comment is simply a quote from the piece: I cannot imagine such an arrangement on a secular campus occurring today.