For decades, international testing data have shown that the United States, for all its leadership in technological innovation and economic success, has been, at best, so-so in teaching fundamental knowledge to young Americans. Moreover, the situation appears to have worsened, aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has not recovered to anemic pre-pandemic levels since. And, a recent RealClear Investigations report documents that our K-12 schools are enhancing mediocrity by worsening an already wrongheaded grade inflation by continuing to give students high grades even as their learning continues to decline. As one refreshing voice of sanity, Maryland education chief Carey Wright put it, “If you set the bar low, that’s all you are going to get. But if you set the bar high for students, and support teachers and leaders, it [higher student performance] is doable.”

College professors are doing the same thing. College grades today are dramatically higher than they were decades ago: When I started teaching in the 1960s, the most common grade in survey courses in my field of economics was “C,” while today it is more commonly a “B.” Are students getting better?

[RELATED: Why Do Education Schools Have Such Low Standards?]

Short answer: No. A variety of testing data show shocking ignorance even among college students. Rather than being a corrective force mitigating the partially woke-induced behavior on the part of the K-12 establishment, the colleges seem to be encouraging it. This was revealed starkly in a recent report by the American Council of Trustees and Alumni surveying 3,000 college students, Losing America’s Memory 2.0. Examples: more students thought President Joe Biden was President of the Senate than the correct answer, Vice President Kamala Harris. Most of those surveyed did not correctly know that U.S. Senators serve six-year terms, whereas House members serve two years. Fewer than two in five students could name the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court—John Roberts. Less than one in three respondents knew that James Madison is considered the father of the U.S. Constitution. I suspect similar testing of scientific literacy would show similar results. Also troubling: a majority of respondents indicate they self-censor when discussing politics, implying fear of negative consequences from freely expressing themselves.

Like many Americans, I am appalled by the prevailing Woke Supremacy at many American colleges that disdains intellectual diversity and lively debate. I deplore anti-Semitism and the lack of civility and respect for fellow students exhibited by a campus cancel culture. I deplore the waste and administrative bloat. But the biggest deficiency is often hidden: our students are not working anywhere near their intellectual capacity and the colleges are doing nothing to reverse that. Already victimized by a K-12 system that does not prioritize learning and discovery, students are further disadvantaged by a similar mindset at the college level.

At elite schools, advanced students’ average grade point average is often well above 3.50: between a “B+” and “A-.” Grades are almost meaningless in separating the truly exceptional students from the merely fairly competent ones. Time use studies show that the typical college student in the mid-20th century worked 40 hours weekly taking classes, studying, writing papers, preparing for exams, etc. Today, the figure is 28 hours–30 percent less. Students are getting higher grades for less work.

[RELATED: More Diversity, Lower Standards]

Who is going to fix this problem, and how? The good news is this problem is not costly to solve. The bad news is that university authorities have ignored it for decades and are not likely going to fix it on their own. If university governing boards acted responsibly, they would take action. For example, they should mandate that the cumulative undergraduate grade point average for the student body could not exceed 2.60 for freshmen and sophomores and 2.90 for juniors and seniors. Academic units would then have to find a way to enforce those standards, with failure to do so leading to forfeiture of a large portion of the salary raise pool. If grades suddenly became much more meaningful, more serious studying would occur.

Other remedies are possible: public universities might see grade regulation by state governments, which would be arguably a mixed blessing at best. We could also put some academic performance standards into federal Pell Grant and student loan programs, and schools should have skin in the game—suffering from loan forfeiture. It is time for American college students to work harder and party less.

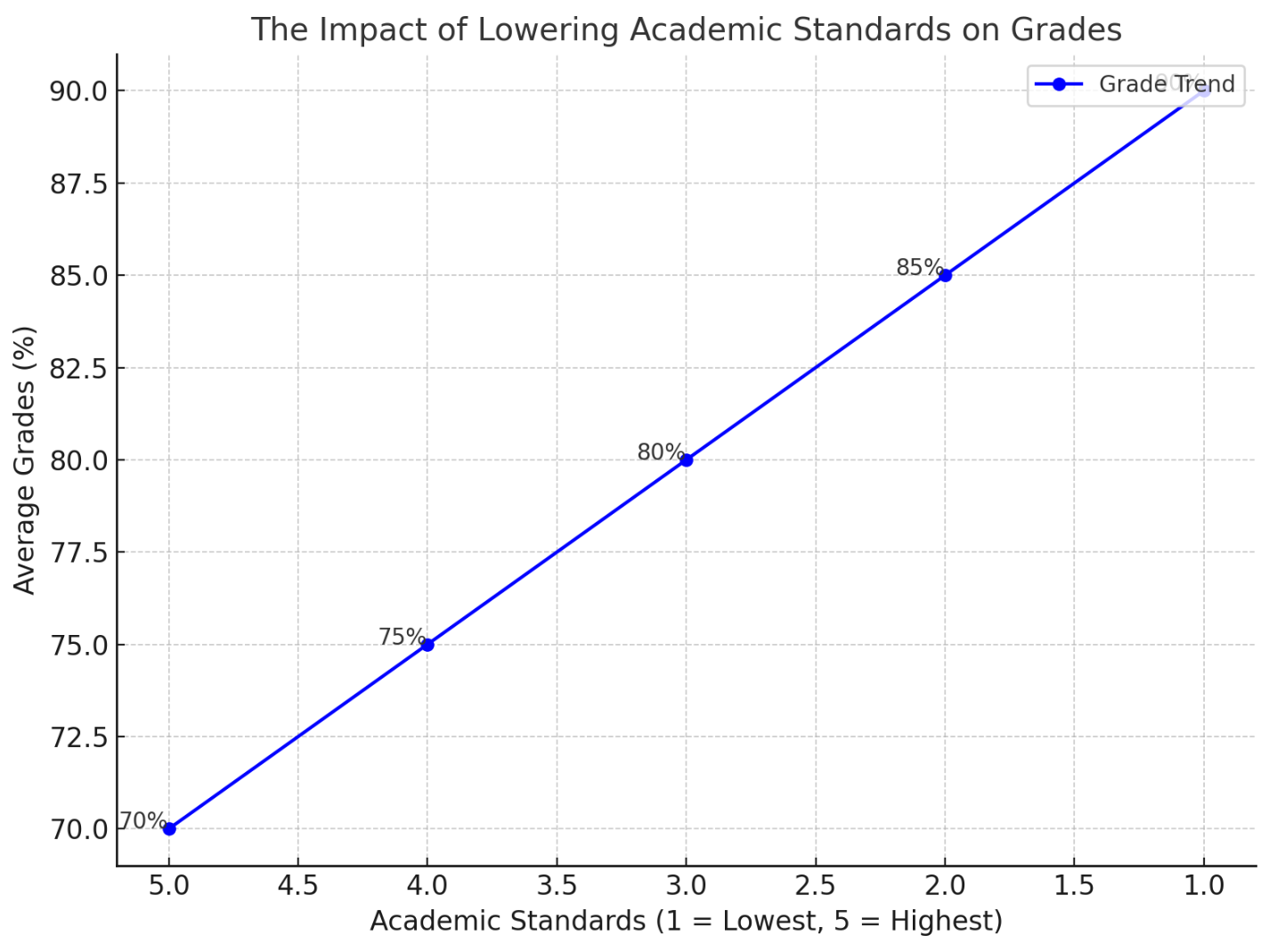

Graph created using AI for illustrative purposes; data does not reflect actual measurements.

Let us be realistic – for all kinds of reasons, bad and worse, faculty cannot grade in the way suggested. So, instead of grading, let us rank, by quintiles, a once common system in the US. Student “grades” would be 1-5 and F. You get a 1 for being in the top quintile, and so on. For classes smaller than 10, you would rank by halves, top or bottom, and F. Grade inflation/deflation would consist of rounding more or less generously when the numbers didn’t work out perfectly, but I’d be content with that.

Toyota established itself in the American auto market with a reputation for quality, that every car that came out of its factory was of higher quality than the junk that Detroit was making in the 1970s, and it was.

A century ago, before photocopiers and laser printers, higher education was like Toyota — the reputation of the university stood behind each and every one of its graduates. GPAs didn’t matter because no one outside the Registrar’s Office would ever see them — a “Harvard Man” was a “Harvard Man”, no one knew if his GPA had been 3.4 or 2.4…

GPA, quintile, whatever — if it were (a) statistically accurate and (b) available to employers, it would make half of the awarded degrees essentially worthless. There are people like me who tell students (and their parents) to drop out if they have less than a 3.0 at the end of their freshman year, you would have major shrinkage in an era of declining demographics and institutions would be unable to survive that.

What institutions need to do is bring all their students up to the quality level reflected by their grades. Toyota didn’t get where it is by just producing some good vehicles, Toyota got where it did by *all* of its vehicles being of good quality.

I tend to disagree that there should be an absolute ceiling on average grades in a department. If the department improves its teaching or attracts better students, the students might actually learn more and deserve better grades. I would suggest that any average grade increases be limited by measurable improvements in student learning.

There is another thing not being mentioned here — and which those under age 50 probably aren’t even aware of — students didn’t have computers until the 1990s.

The student of today isn’t using a typewriter. Instead, today’s students have a word processor that includes spell check and the ability to re-arrange paragraphs without retyping the entire paper. One has to have written papers with a typewriter to understand what I mean, but I have no doubt I would have gotten better grades today because my papers would have been far better quality.

Second, students had to physically go to libraries and look up things on paper. As an undergrad, I remember one of my fellow students going to a law library some 120 miles away to look things up there — today, that would be on my laptop, accessible from my dorm room.

It’s called the World Wide Wasteland for a reason, but the Web did not exist until 1993. While 99% of it is garbage, the undergrad of today has access to more knowledge than a professor did back then. And maybe some of this knowledge is making it into student work, perhaps in some cases even properly attributed and not plagiarized…

So if I were an undergrad today, with the basic $250 laptop sitting on my knee, I’d get better grades than I did because my papers would have had more content in them and have been much neater, without the inevitable typos. I doubt I am the only one.

Hence by this matrix, students today ARE better — and I’d like to compare the student of the 1960s to the student of today in terms of knowledge acquired as it is a whole lot easier to learn things today.

I’m going to offer a different approach — make all classes pass/fail.

Life is that way — you either get fired or you don’t, you either get promoted or you don’t, you either get the truck through the snowstorm or you die in a wreck on the highway.

Gradeflation really didn’t exist before the photocopier — the diploma was the indication that the person had met the standards of the institution, and the letters of recommendation could speak to the individual’s qualities.

No one wants to see a diploma anymore — now it is a transcript with a GPA calculated to four decimal places that matters. And hence why shouldn’t we expect to see gradeflation?

No institution would dare do what Professor Vedder advocates because it is competing with other institutions for students. If I can go to University Alpha and get a 2.0 GPA but go to University Beta and get a 3.5 GPA, where do you think I am going to go?!?

So University Alpha will have a better “reputation”? It’ll still go bankrupt….

And you want to put GPA requirements in Pell Grants? You won’t even have to wait for the race riots to start because of that….

Ignorance is bliss. Good luck.

Do you honestly believe that the faculty at University Alpha are really going to insist on academic standards that will cost them their jobs because the university went bankrupt?

A few close to retirement might, but the rest aren’t going to have that luxury.

Another person who’s only contribution is to get in the way of those trying to deal with the issue.

Woe is us, we cannot solve grade inflation, poor learning or any problem due to competition.

You go to the inflater-U, others will to, but soon all will know that this is a bogus University and its graduates will be less desirable.

The road to hell is paved with such excuses.

“…but soon all will know that this is a bogus University and its graduates will be less desirable.”

I respectfully disagree — how will all know, and how will they “soon” know?

At last count, there were 5,382 colleges in the country — exactly who is going to compare all of them, and on what basis? (If you think that the US News & World Report’s rating is accurate, I can get you a really good deal on this bridge in Brooklyn.)

More importantly, a college’s reputation isn’t based on those who graduated in 2024. Instead, it is based on those who graduated in 1984 and were taught by professors who had been hired decades before that.

So who is going to know that this has become a “bogus university”? And how are they going to quickly know it?

Even if it’s higher GPA comes out — and it isn’t like it is going to advertise that — it can say that it’s faculty are better teachers and care more about the individual student. As that would legitimately raise student GPAs, how are you going to prove otherwise? Likewise it could point to its student support services being more effective, a better quality of student life on campus, and maybe even better food in the dining commons. Again, how are you going to prove otherwise because all of this legitimately affects student success.

Second, it’s the individual graduate who is applying for the job, not the whole graduating class. And who is going to deal with enough graduates of InflaterU to make any objective judgments about how it has changed from what it was in 1984.

It took Claudine Gay for people to realize how much Harvard has changed…