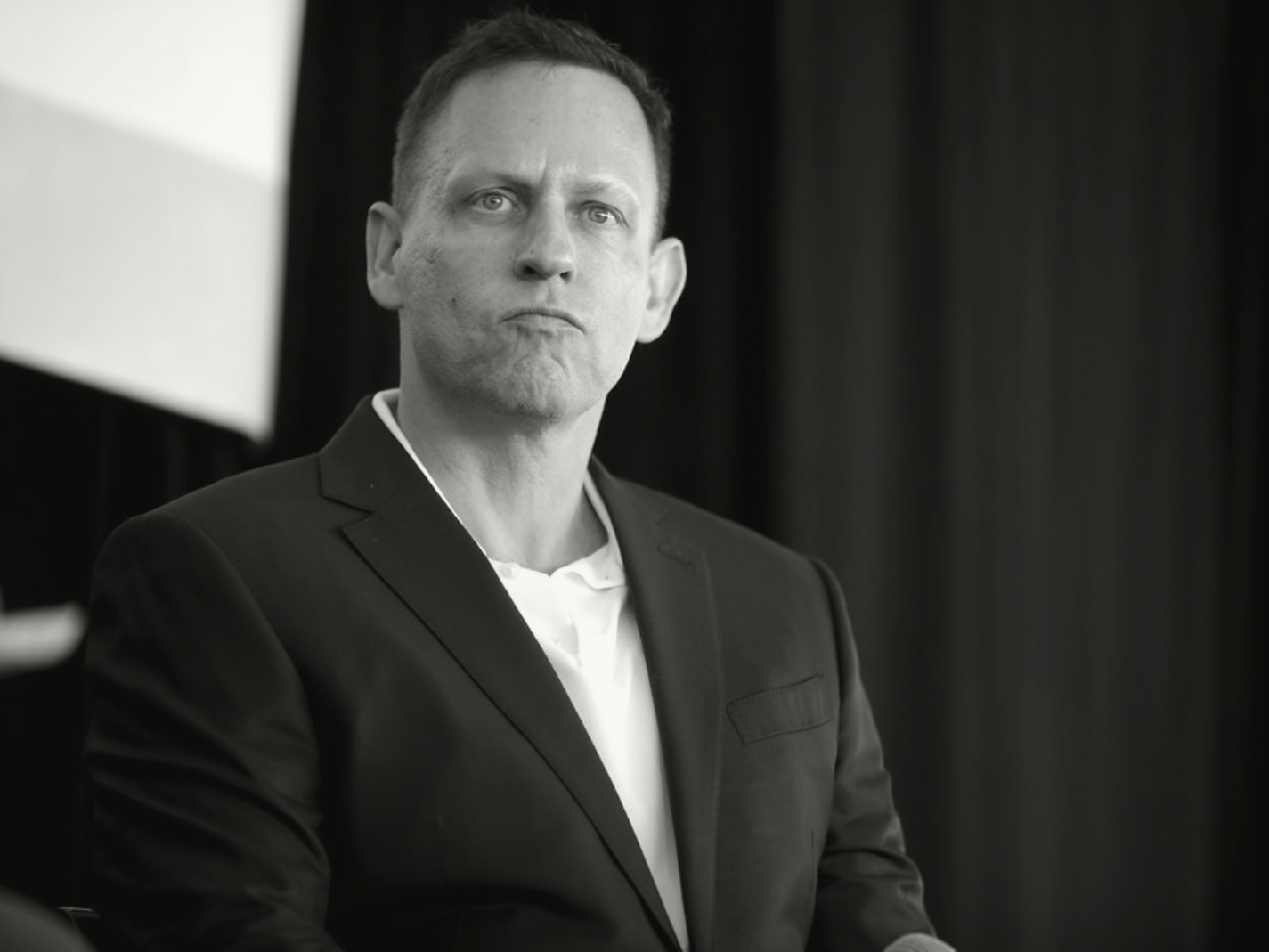

From October 28th to the wee hours of October 31st, I attended Hereticon at the Faena Hotel on Miami Beach. Put on by tech billionaire Peter Thiel—who has been frequently and unfairly villainized by the mainstream media and academia—through his Founders Fund and organized by the indefatigable Michael Solano, Hereticon is a conference for those who are willing to think and say the unthinkable. As explained on the Hereticon website:

Right at the peak of our last pandemic, Founders Fund hosted the first Hereticon, a ‘conference for thoughtcrime.’ Our thinking was simple: dissent is worth protecting. Most new ideas are wrong, or useless. Some are even dangerous. But from science and technology to business and faith, progress is a history of persecuted weirdos, so that is where we stand, and that is what we celebrated.

I attended the conference with my husband, Nick Pope, who formerly investigated UFOs for the UK Ministry of Defence. Hereticon hosted the world premiere of his new documentary, Apocalypse Covid, which focuses on government overreach during the pandemic. I moderated a fireside chat with him about the film afterward. I also participated in a panel for the Q&A following a screening of the film The Unbelievers—part of Hereticon’s Forbidden Film Festival. My main talk was a moderated discussion with Quillette founder Claire Lehmann, during which we discussed how Native American culture, as popularly conceived, is a modern construct that distorts history. We also addressed the Biden administration’s recent Indigenous knowledge mandate, which effectively gives recently created tales equal—or sometimes greater—weight than science.

Due to the controversial nature of many of the talks and topics, and to encourage open discussion, Hereticon follows the Chatham House Rule, which allows attendees to share information and comments they hear without revealing names or sources unless they have explicit permission. There were no names on our passes; some attendees opted not to have their names in the program or on any online promotional materials, and some even used pseudonyms at the event. For this reason, few names appear in this article.

One may ask: What is being said that is so controversial? And some speakers even suggested that Hereticon is no longer full of heretical ideas since the conference—in its second running—has created a space for controversial topics. Yet, the many conversations I had and talks I listened to would indeed be considered heretical on modern university campuses and elsewhere. Let me give you some examples:

- One of the speakers discussed the reality, genetic component, and importance of IQ. Research on IQ tests and their significance as predictor variables is one of the few areas of social science research that is consistently replicable. The speaker raised the thorny issue that higher IQ, even after controlling for socioeconomic status, correlates with lower crime rates, greater mental health and well-being, and greater self-control. Since IQ correlates with many positive traits and life outcomes, members of the audience further suggested that it is crucial to choose one’s mate based on IQ. Race and country differences in IQ were also raised since there is considerable evidence of an unequal distribution of high IQs. These IQ truths help explain unequal education, crime, and wealth outcomes. Yet, liberal academics posit that the uneven outcomes are due to systemic racism or unfair systems, such as the justice system. Those who bring up such topics in modern academia will be called racists or eugenicists, perhaps even compared to Nazis. These are cancellable offenses to liberal academics, where the common belief is that intelligence is doled out evenly, but opportunities are not, and, thus, it is society’s fault for uneven outcomes.

- Another talk focused on the importance of fossil fuels. This speaker started by asking who was concerned about climate change; most people, even at Hereticon, raised their hands. The speaker then put forth his well-sourced argument that increasing fossil fuel consumption would make the world a better place. He showed how fossil fuels, which are a cheap and reliable form of energy, have made the world a better place—from saving babies to reducing old age deaths, especially from the cold. Never before has climate had less influence—especially negative influence—on our lives, and this is in large part a result of fossil fuel use. Interestingly, the speaker put forth that to win over those with concerns about fossil fuel use, speaking to them on an emotional level about babies being saved in incubators may work better than arguing with data alone. His talk would have certainly been labeled misinformation by mainstream reporters, and he would have been called a “climate denier”—mimicking the term “Holocaust denier.”

- A speaker raising concerns over the Islamization of Europe explained that the Muslim Brotherhood, which has given rise to ISIS and Al Queda, works as a loose network on a local level. They start off by luring people in through charity at a local level. But, once they grow to a large enough size in any location, they turn to violence, especially against nonbelievers. She stressed that Europe is running out of time to protect Western Civilization since Muslims are immigrating to Europe in vast numbers and have far more offspring than the Europeans. The only measures that can prevent this Islamic takeover of Europe, according to the speaker, is deportation—especially of those involved with the Muslim Brotherhood, which should be considered a terrorist organization—and protection of borders. Her proposals would certainly be labeled as Islamophobic in most university communities. And a professor stating such a position would most certainly need legal protection to keep their job!

- During an evening event called Fight Club, brief debates covered topics such as whether pornography should be banned, if artificial intelligence (AI) should be regulated to slow progress, and whether biological sex is real. The debate on biological sex featured an evolutionary biologist on the “yes” side and a trans woman—who identified her gender at the start of the debate—working in private-sector gene editing on the “no” side. The evolutionary biologist argued that sex is an evolved reproductive strategy seen in many plants and animals, explaining that it is determined by gamete type: females produce large gametes called ova or eggs, while males produce small, mobile gametes called sperm. The gene editor argued that technology may be able to change gametes in the future, and there has been a uterus transplant that resulted in a female with XY chromosomes giving birth—this case involved an intersex woman born with XY chromosomes and androgen insensitivity. Interestingly, this gene editor also brought up the issue of body dysmorphia and the importance of being able to transform one’s own body. The audience, which was polled before and after the debate, sided with the evolutionary biologist and the position that biological sex is real. Discussions continuing in the elevator revolved around the issues that transgender changes are mainly cosmetic and that any technological advances that enable males to become pregnant and have babies still doesn’t negate the fact that biological sex is real. What’s interesting about these debates is that the sides put forth their best arguments, and neither side was canceled or silenced, as has happened so many times in academia. For instance, the American Anthropological Association canceled my talk on the importance of biological sex in skeletal research. The panelists were compared to eugenicists, fear of harm to the anthropological community was raised, and we were all branded as transphobes. Hereticon was refreshingly different.

Throughout the conference, mingling led to interesting topics—I met people who were working on cloning brainless animals as a future solution to the scarcity of organ donations. These individuals had to come to the United States because such research is verboten in their homeland of Germany, where they could face a three-year prison term for working with embryonic stem cells! And, at the Apocalypse Ball—which was followed by a late-night DJing performance by Grimes—costumes were not policed with inane statements such as “my culture is not your costume.” Thus, there was a doctor of eugenics costume; some came as “white men for Harris;” one person came as a Haitian chef with a bloodied toy cat hanging out of his apron—these elicited laughs, not scorn. And it all took place in a beautiful location with a string quartet, dancers, and an abundance of fine foods.

Hereticon was an opportunity to meet mostly young people who are willing to challenge mainstream ideas and to think and talk about the future in ways that just aren’t allowed on university campuses today. Debate was alive in many corners, from worrying about the AI takeover to looking toward an AI future of solutions to today’s stickiest problems, from films about atheism to the importance of religion in communities, from celebrating sexual freedom to concerns about human trafficking in the porn industry. In short, the crowd was diverse in the most important way—diverse in thought. If this is the next generation of free thinkers, I am hopeful for the future—which was a funny way to leave a conference themed around the apocalypse.

Image of Peter Thiel by Gage Skidmore on Flickr

What arguments does the speaker make regarding the importance of fossil fuels, and how does he explain the positive impact their use has on human life, especially in the context of health and climate change?Regard Kriya Tekstil & Fashion

Yes, he does address these issues. I am currently reading his fantastic book on fossil fuels: “Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas–Not Less”