For a time, I worked at a South African university, where my department still upheld the civilized practice of morning tea. One morning, I happened to arrive a few minutes late but found an open seat at a table just as a senior professor was opining—in very orotund tones, naturally—to some Honours students, “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if scientists ruled the world?” To which I blurted out, “God, I can’t think of anything worse!” He never spoke to me again.

I tell this little story because it illustrates a political dilemma that, in one form or another, has persisted in our culture since Socrates: What should be the relationship between scientists—or philosophers, in Socrates’ day—and the society in which they live? The professor’s lament was rooted in a view of scientists as nobility, as philosopher-kings who are the unique custodians of wisdom and knowledge. My point that day, though I never got to make it, was that scientists, of all people, are particularly bad candidates for political power. Successful scientists tend to focus on small things to the exclusion of all else, are easily distracted, are often wrong, and are always changing their minds—the very opposite of the traits necessary for good governance. In short, which is the better sovereign: scientists or the people?

Much of the “American experiment’s” history has been a long conversation about that very question. Up to the mid-19th century, democracy was favored: science and technology were “useful arts,” instruments to serve the ingenuity and aspirations of a free people, but never to subordinate them. The conversation began to change after the Civil War when John Wesley Powell—the explorer of the Grand Canyon—became head of the nascent United States Geological Survey (USGS). When it was formed in 1879, the new agency was charged with the “classification of the public lands, and examination of the geological structure, mineral resources, and products of the national domain” with an eye to “disposition of public lands” to states and individuals, a clear statement of the Geological Survey as an instrument of the useful arts.

When Powell took over as USGS Director two years later, he changed the conversation, prompted by the question of settlement of the recently acquired arid lands of the southwestern United States. The problem there was water, or more precisely, the scarcity thereof. Powell’s view, which he pursued with characteristic energy and charisma, was that those lands could not simply be opened to settlement by homesteaders. Rather, it had to be managed and controlled by scientific water management principles. This put Powell in conflict with settlers—including Indigenous tribes—already there who, in their view, were managing the southwest’s water resources quite well on their own; thank you. The conflict was not resolved in Powell’s day, but the technocratic “twisted roots” Powell planted have ever since tilted the shifting balance between science as a servant of the people, and science as their master. We’re living with that dubious legacy still.

To be fair, Powell did not act alone but rather reflected broader contemporary social attitudes about science. While Powell was transforming the USGS, the U.S. Congress was considering the establishment of a cabinet-level Department of Science—something that previous Congresses had studiously declined to do. That effort failed, but its ghost remains in the perennial demands to wrap science in political power, which wax and wane with the political tides. Even so, the overall trend toward “scientific governance” has been gradually upward, lofted on the increasingly influential article of faith that “science” is a superior guide to human affairs compared to the messy, grubbing, and selfish interests of the demos. This tendency took flight around the turn of the twentieth century as new regulatory agencies were created, beginning with the U.S. Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Public Health Service, and the Food and Drug Administration. The upward trend continued through the twentieth century, growing ultimately into the alphabet soup of regulatory agencies that now govern our lives. All along the way, doubters of the rise of technocracy were told, “Don’t worry, it’s for everyone’s good! Science says so.”

In 1984, technocracy got a major shot in the arm from a Supreme Court decision, Chevron U.S.A v Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. This decision set in place a doctrine known as Chevron deference. The Chevron case itself turned on an ambiguous definition in the Clean Air Act about what counted as a point source of pollution. The Court’s opinion stated that courts should resolve those ambiguities to favor agencies’ scientifically-informed and, therefore, defer to those experts’ judgments.[1] And boy, did they ever: the Chevron decision is perhaps “the most cited case in American administrative law,” according to Wikipedia. For the majority of subsequent challenges to agencies’ expert opinions, Chevron deference carried the day, ushering in the unelected and unaccountable “scientific deep state” that now takes it upon itself to boss everyone around, all of it predicated on the faith that “the science” knows best. Technocracy was thereby enshrined on Chevron deference.

There it remained until the Supreme Court’s October 2024 term, when the Court issued opinions in two cases that effectively overturned Chevron deference.[2] Now, scientists and agencies must argue their cases on equal footing with all other petitioners. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is alarmed by that prospect; in response, it recently organized a members-only webinar titled “Scientists Respond to the Supreme Court.” A more accurate title would have been “Scientists Oppose the Supreme Court.”[3] Simply put, the AAAS seeks to restore Chevron deference, aligning with its real aim—not the advancement of science but the advancement of technocracy. And it expects its members to get on board.

There were three panelists on the webinar, none of whom were scientists:

- Jeffrey Lubbers, Professor of Administrative Law in the Washington College of Law at American University.

- Joanne Padrón Carney, Chief Government Relations Officer in the AAAS Office of Government Relations and

- Theresa Harris, Program Director of the AAAS Center for Scientific Responsibility and Justice.

Prof Lubbers gave what I thought was a pretty fair overview of the legal issues surrounding the decision, so that was certainly informative. The other two panelists’ aims were more focused on how to restore technocracy. The concern was particularly high for the pet causes of the scientific deep state: environmental protection (the EPA is the largest employer of scientists in the scientific deep state), public health—remember COVID-19?— and the deep state’s Shangri-La, climate change. The subtext throughout was consistent: How can the technocratic agenda be advanced now that the court has stripped away the robes of Chevron deference?

And there were proposed solutions aplenty. Congress could simply enact Chevron deference into law, which Sen Elizabeth Warren already has proposed. And, of course, more money and personnel: add more science staffers to the already staff-heavy House—9,000 staffers of all types—and Senate—6,000. Pour more money into the Congressional Research Service and the Government Accountability Office. Finally, resurrect or create new federal agencies that would give “science” the outsized voice that Loper Bright took away. Scientists should come in and “educate” judges, lawyers, and politicians in the ways of science to force the icky proles to go back again to pleading their interests with hat in hand and trembling knees.

God, I can’t think of anything worse.

[1] Loper Bright v Raimondo, and the court overruled a long standing doctrine of judicial deference to regulatory agencies known as the Chevron doctrine. In a related case, Corner Post v Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, allowed plaintiffs to challenge regulatory rules that relied on Chevron deference.

[2] From the syllabus of the decision: ‘Under the Chevron doctrine, courts have sometimes been required to defer to “permissible” agency interpretations of the statutes those agencies administer’

[3] Access to the recording and slides of the webinar requires being a dues-paying member of the AAAS. It is located behind the members portal: https://members.aaas.org.

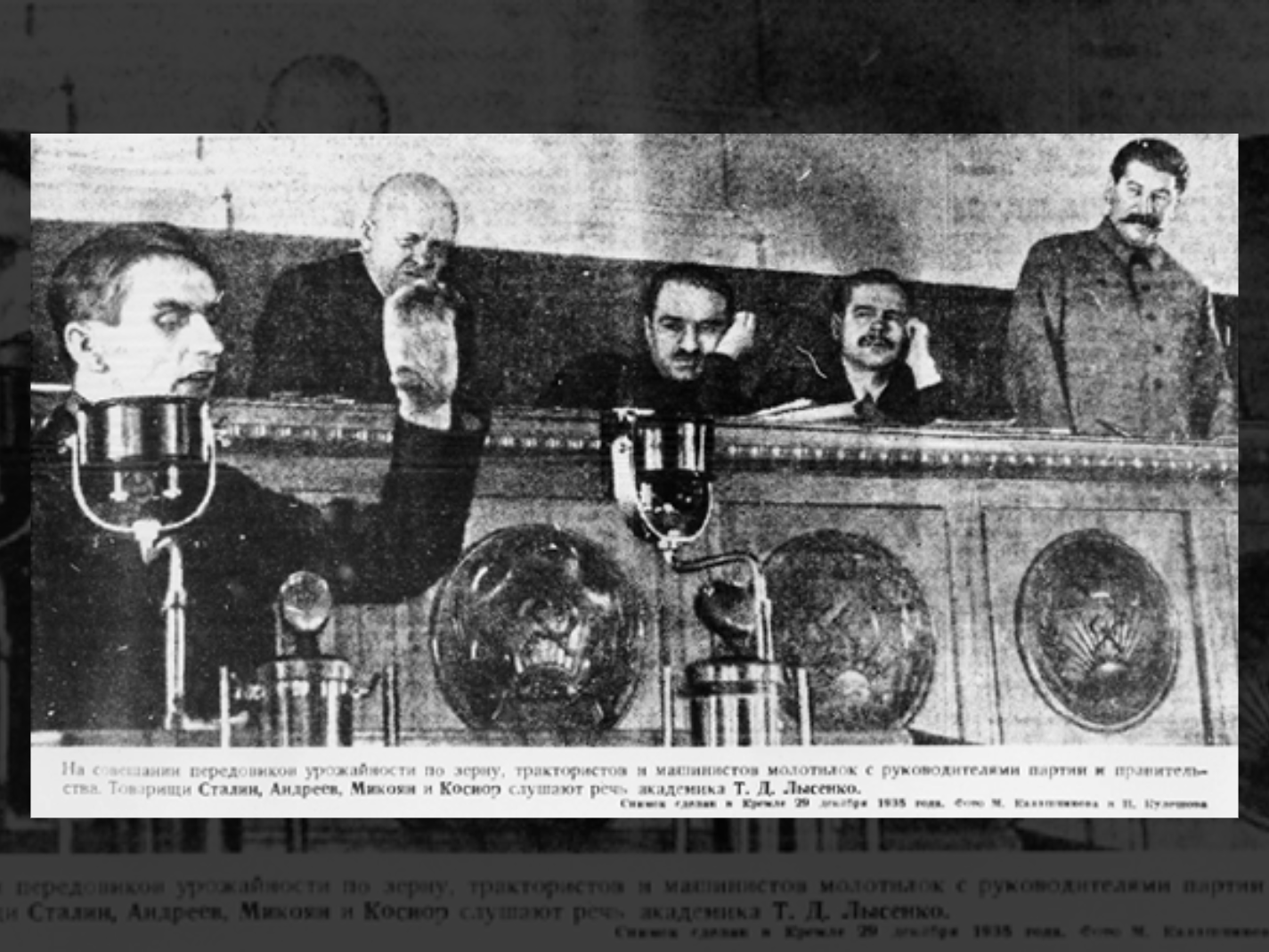

Image: “Trofim Lysenko speaks in the Kremlin in 1935. In the background (from left to right) are Stanislav Kosior, Anastas Mikoyan, Andrei Andreev, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin” — picryl.com