“What kind of a friend could pull a knife

When it’s him or you and his kids need shoes?

What kind of friend would do you in

When the bomb goes off and the shelter’s his? …

What kind of friend would tell you lies

To spare you from the bitter truth?

And what kind of friend could stoop so low

As to shield your eyes from the mirror’s gaze?”

The late Mark Heard’s 1991 song “What Kind of Friend,” written to illuminate the irreplaceable and supreme friendship Christians find in Jesus Christ, is also about the brokenness, disappointments, and heartaches inevitable in all human relationships. Counterintuitively, the latter has come to be epitomized by the complex dynamics between American progressives and advocates for racial equality or equity from both aisles of the political lane.

It is not a surprise that conservatives detest the progressive program on race relations, which is thought to be a counterproductive and patronizing ideal predicated on division and envy. But left-leaning policymakers have also frequently betrayed the trust of their race-focused “friends,” especially when handing out government preferences based on race, the battle cry of racial justice collides with other goals of progressivism.

The less conspicuous rancor between the progressive belief system and the struggle for racial equity and justice is not an aberration. The paradoxical relationship is a system feature as old as the early days of American progressivism at the end of the 19th century, even before the pinnacle of FDR’s New Deal.

Contending with the economic depression in the 1890s, social reformers platformed a series of movements to improve labor conditions, tax the rich, centralize railroad and utilities, and monetize silver. They borrowed from the “Social Gospel” doctrine pioneered by leftward Christian leaders, who proselytized socioeconomic transformations in place of salvation. Progressives even formed the populist People’s Party to represent the urban poor, the debt-struck farmers, small businessmen, and the laborers. But American progressivism, at its onset, was a middle-class movement led by “doctors, lawyers, ministers, ankers, shopkeepers … office workers and middle managers,” observes historian Wilfred McClay.

At a time when America was undergoing seismic transformations from a rural, decentralized country on the world’s periphery to an urbanized, cosmopolitan world power, early progressives brought into motion much-needed reforms in pursuit of the public good, such as the eight-hour workday, restrictions on child labor and checks on monopolies. Nonetheless, as self-interested bourgeoise claiming the moral high ground when it was convenient as they truly were, these reformers were oblivious to the plight of racial and religious minorities by supporting immigration restrictions and racial segregation as a way to purify American society. In the same vein of implicit paternalism, a significant number of progressives endorsed eugenics, selective infanticide and forced sterilization as methods to get rid of the undesirables.

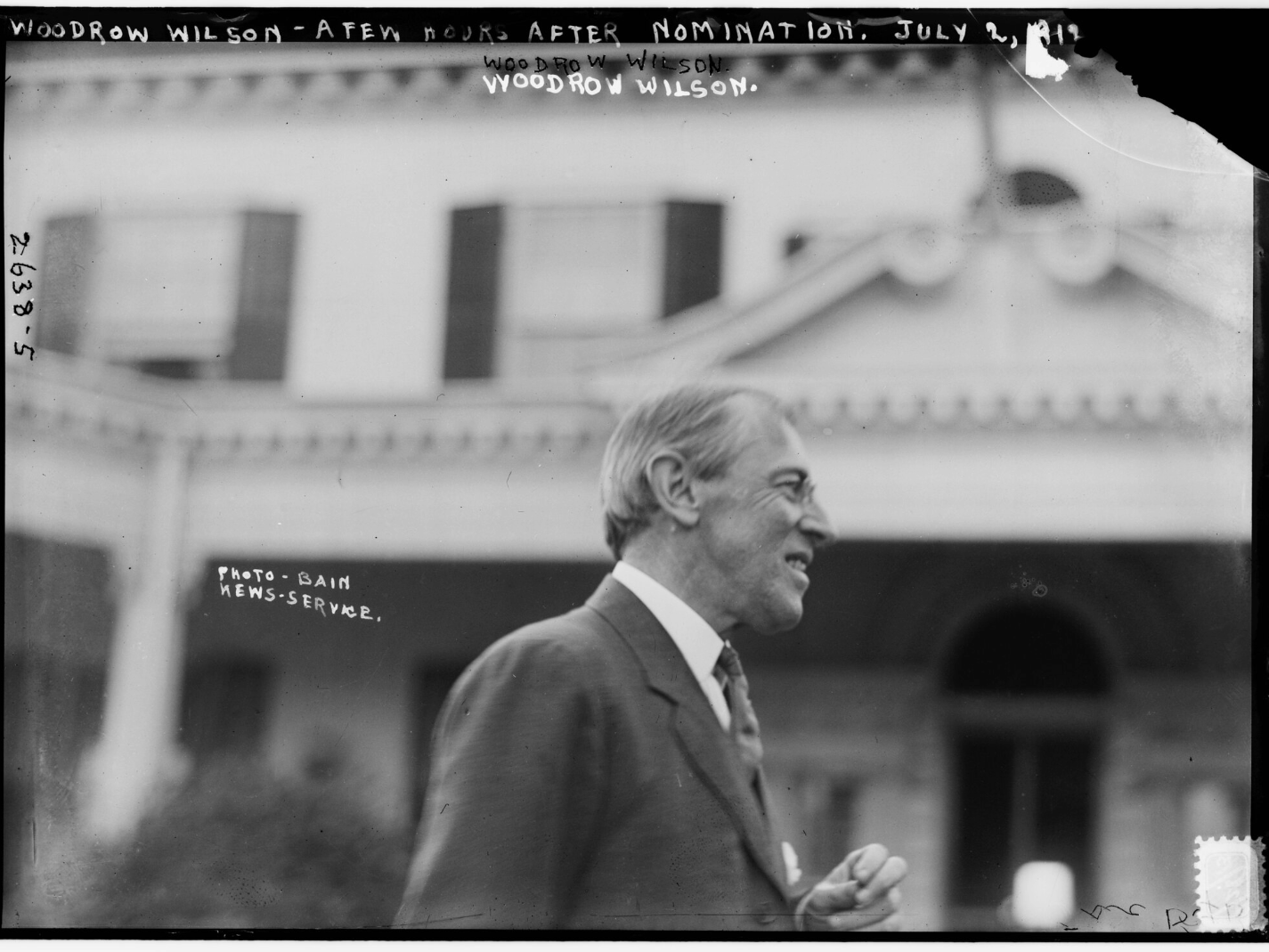

Woodrow Wilson, America’s first Southern president since before the Civil War and the second to identify as progressive, notably advanced a segregationist ideology and subscribed to the “Lost Cause” narrative, which sought to restore white dominance in the postbellum South. While it is essential to evaluate Wilson based on the entirety of his governing record—including significant progressive labor policies and the consolidation of federal power in banking, transportation, and construction—his racial biases were evident even to his contemporaries. These prejudices were emblematic of the political movement that propelled him into office.

Much like their predecessors, modern-day progressives continue to practice paternalism and implicit condescension towards minorities.

In California, the movement to institutionalize slavery reparations, which started in 2020 after state lawmakers approved a bill to assemble a Reparations Task Force, seems to become an embarrassing blunder for progressives across the country. When the California State Legislature concluded its 2023-24 legislative session at the end of this August, the Legislative Black Caucus quietly canceled two key reparations bills, which would have established a freedman affairs agency to confirm claims and created a state fund for reparations.

This sudden move, after the Black Caucus had pledged full support for cash stipends, housing benefits, educational assistance, environmental justice, and more to Black Californians, incited protests by supporters of reparations. The Coalition for A Just and Equitable California, a vocal nonprofit lobbying for race-based reparations, accused the Black Caucus of lying and cheating. One group leader even went so far as to threaten the politicians with their votes against the Democratic presidential nominee. Ironically, it was a Republican state assemblyman who intervened and attempted unsuccessfully to introduce the two proposals on the assembly floor for discussion out of respect for the democratic process.

Days later, the Governor vetoed another bill to give back “stolen” or wrongfully taken land to black families as a result of “racially motivated eminent domain.” Due to an overhanging $68-billion budget deficit and other more politically expedient objectives, California’s political leadership sacrificed all high-cost reparations bills. The lofty ideal of righting the wrongs of chattel slavery remains a pipe dream, even in America’s most diverse and progressive state.

When it comes to delivering promises on racial justice, the left is not just paying lip service but also actively engaging in sabotage by way of grifting. In 2021, the San Francisco City Hall rolled out the Dream Keeper Initiative, a $300-million pool of public funds earmarked for ambitious programs targeting the city’s “historically underserved Black residents” with benefits in entrepreneur training, grocery vouchers, down-payment assistance, educational grants and more. The City Controller reported that $140 million has been spent so far, of which misspending and financial mismanagement are identified. Facing evidence of cronyism and corruption, the former head of the Human Rights Commission who oversaw the initiative’s rollout resigned, and the Mayor locked down new grant awards. Individuals expecting to receive assistance from the initiative, such as this college student who is counting on an alternative scholarship after a traffic accident made her ineligible for a track scholarship, are disillusioned.

Woodrow Wilson explained racial segregation as a necessary policy to “avoid friction.” Joe Biden accused conservative states of instituting “Jim Crow 2.0.” Barack Obama belittled black men whom he said were clouded by misogyny for not voting for his Democratic protégé. The fact that progressivism has always had hypocritical, compromised, and distorted views on race in America is just old wine in new bottles.

Image by GPA Photo Archive — Woodrow Wilson, President 1913 – 1921 — Flickr

A good distinction well made.

The author makes a mistake common to those who discuss the “Populist/Progressive Era” — failing to distinguish between the two. It’s an easy enough mistake to make in that the goals of the two were somewhat concurrent at times, and as the Progressive movement was urban based (where the newspapers were)., it is better documented than the Populist movement was. Furthermore, as the Populist movement was centered around the rural Grange (the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry), it is often commingled with the Granger movement as both championed some of the same causes.

The coinage of silver (i.e. inflating the money supply) and regulating railroad freight rates (i.e. making the railroads common carriers) were farmer’s issues which were championed by both the Grangers and the Populists. By contrast, the 8-hour workday was an urban issue championed by the Progressives. And at the most basic level, all three movements were a response to the so-called “Robber Barons” who arose to prominence in the latter half of the 19th Century.

Woodrow Wilson was a Progressive, not a Populist, and what a lot of people don’t realize is that he segregated both the Federal Government and Washington DC. In 1872, then-President US Grant was arrested for speeding — by a BLACK police officer. Before Wilson, both city and Federal workforce were integrated.

Individual versus collective rights was the dispute between Booker T Washington and WEB DuBois, and the early racial discrimination cases and the current disparate impact suits.

This (and common sense) is the issue with the concept of reparations for slavery. Less than half of American Blacks have an ancestor who was a slave, and not mentioned in any of this is subrogation to those whose ancestors DIED freeing the slaves. One White man from the North died for ever 10 slaves freed. My great-grandmother was orphaned by the Civil War — where is *my* handout?!?

The distinction I make is that the Progressives were largely collectivists seeking collective (group) rights and benefits, while the Populists and Grangers were largely individualists seeking individual rights. The distinction goes all the way back to the French Revolution and its collective values of “liberty, fraternity, and equality” versus the American Revolution and its individualistic values of “life, liberty, and property.”