Author’s Note: This excerpt is from my weekly “Top of Mind” email, sent to subscribers every Thursday. For more content like this and to receive the full newsletter each week, sign up on Minding the Campus’s homepage. Simply go to the right side of the page, look for “SIGN UP FOR OUR WEEKLY NEWSLETTER, ‘TOP OF MIND,’” and enter your name and email.

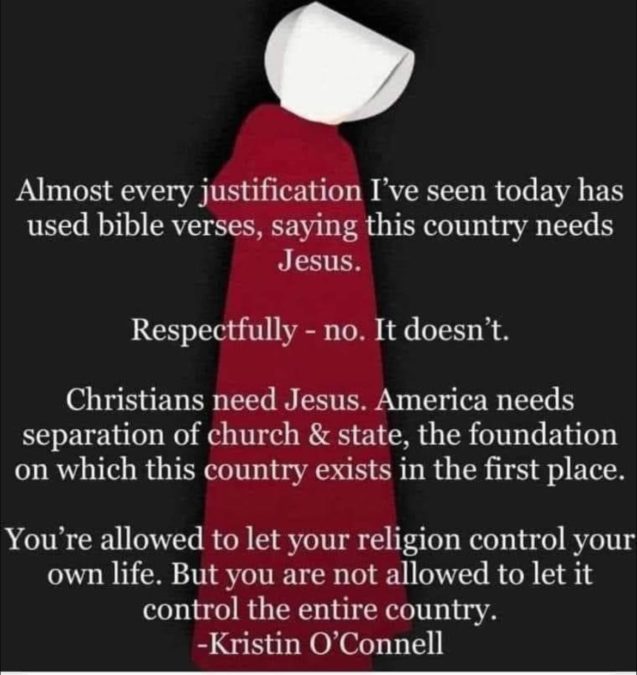

There’s never a dull moment during election season, but what leaves me astonished isn’t the predictable political theater—it’s the breathtaking ignorance of basic concepts underpinning our nation. On Sunday, a college graduate graced my Facebook feed with this gem of misinformation:

Now, I won’t name and shame, but I do feel frustrated that someone with a college degree could walk away with such a flimsy grasp of religion’s role in shaping society. To be fair, I don’t lay all the blame at their feet. Our educational system is churning out graduates without even a cursory understanding of the foundational role religion played in America.

So, let’s clear the air. The United States wasn’t founded on “separation of church & state” in the way this post says. That phrase? It doesn’t appear in the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, or any other founding document. It comes from an 1802 letter Thomas Jefferson wrote to the Danbury Baptists, reassuring them the government wouldn’t meddle in their religious affairs. He wasn’t erecting an impenetrable wall between religion and public life—he was promising to protect religious freedom from government interference.

Yet here we are, with college grads thinking that “building a wall of separation between Church & State,” as Jefferson wrote it, means “keep religion out of everything”—a blunder that wouldn’t survive five minutes in a real history class. And who can blame them when the institutions tasked with educating them gloss over the fact that the Founding Fathers saw religion—Christianity, in particular—as essential to moral governance?

George Washington nailed it in his Farewell Address: “Religion and morality are indispensable supports” of political prosperity. John Adams took it further: “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

Western law itself is rooted in Christian ethics. Murder, theft, perjury—these aren’t secular inventions. They’re biblical commandments brought into the legal frameworks we rely on today. Legal historian Harold Berman noted in Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition that Western law was founded in the church and on Christian values. The very movements the left loves to champion—like the abolitionist movement—were heavily rooted in Christian ethics. Without Christian conviction, the push to end slavery would’ve fizzled. Leaders like William Lloyd Garrison and Theodore Parker viewed slavery as an affront to God’s moral law. Should those Christian leaders have kept quiet? Should they have refrained from imposing their moral convictions on society?

And, hey, we just had Columbus Day. Intellectuals and dumb intellectuals alike have debated the merits of keeping Christopher Columbus statues. Leftists have toppled them. But in the frenzy, the broader historical context of his arrival has been lost. That is, should the Catholic missionaries and explorers who landed on American shores have remained silent when they saw human sacrifice, ritual killings, and child sacrifice? Bartolomé de las Casas, a Spanish priest—whom, yes, I know has been critiqued for exaggerating things—nevertheless documented these horrors in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. He condemned such practices but saw them as evidence of the need for Christian conversion. Should the missionaries have turned a blind eye in the name of cultural relativism?

The modern argument that Christianity shouldn’t influence society reveals a profound misunderstanding of history and the faith itself. Christianity isn’t a private club where you keep your beliefs to yourself. It’s a worldview that calls its followers to engage and transform the world. As Vatican II’s Gaudium et Spes reminds us: “The Church…carries on the work of Christ.” Christians are called to be the “salt of the earth” and “light of the world,” (Matthew 5:13-16)—not retreat into hiding.

How are we graduating people with such a juvenile understanding of religion’s role in public life? You spend four years and a fortune for what? The ability to regurgitate shallow misinterpretations of “separation between church and state” on Facebook? Our universities are failing at their most basic task: teaching. Instead, we’re producing eligible voters who can’t grasp the basic principles of their own country, let alone religion’s influence on law, politics, or society—yet vote they will.

This isn’t just ignorance—it’s dangerous. As John Adams warned, without religion, the Constitution becomes “wholly inadequate.” So, as I said to the poster, respectfully, America doesn’t need more confusion about “separation of church & state.” It needs a proper education about religion’s role in shaping its moral and legal foundations.

Until our institutions start teaching that, you’ll just have to rely on Minding the Campus to set the record straight.

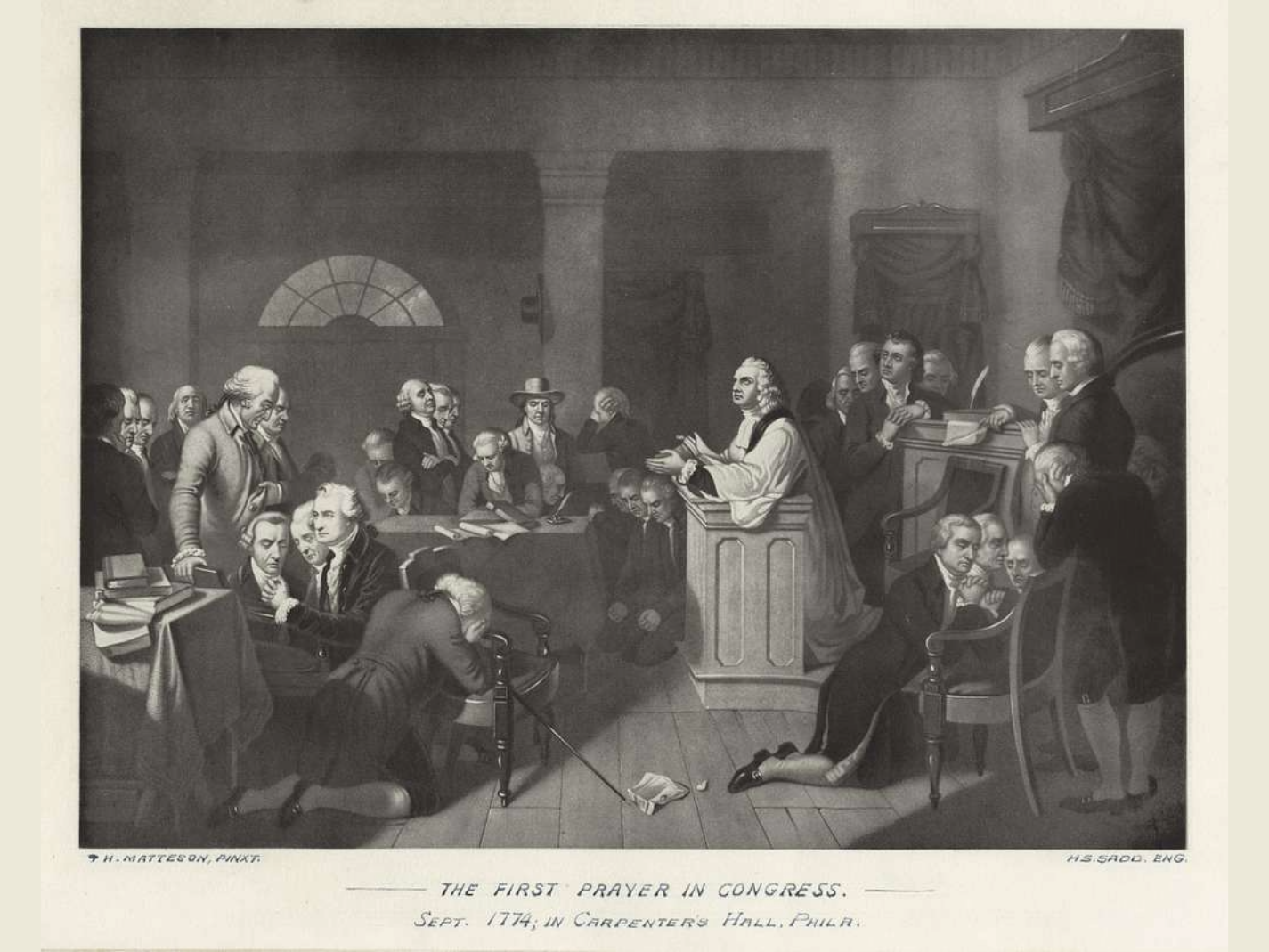

Image: The first prayer in Congress, Sept. 1774 — NYPL’s Public Domain Archive

Then-President Jefferson’s letter to the Baptists of Danbury (CT) needs to be viewed in the context of both the election of 1800 and the Hartford (CT) Convention of 1814.

John Adams and the Federalists were soundly defeated in the election of 1800 that put Jefferson in the White House, but New England remained a Federalist stronghold and would actually consider seceeding in 1814. The Baptists had split off from the Puritans omn the grounds that the Puritans weren’t strict enough. There were also theological issues.

At this time (and until 1855 in MA) the Puritan Church, which was becoming the Congregational Church, was the official state church of the New England states. In MA, to become a town, one had to convince the legislature that you had (a) the tax base to support a minister and his wife and (b) had found one willing to move to your town and be your municipal mimiister. The Baptists weren’t liked, although in 1820 (MA) they didn’t have to pay the church tax anymore if they could prove they were supporting a Baptist church.

Remember too that John Adams’ father in law was a minister, who never thought that a mere lawyer was good enough for his little girl, he had wanted her to marry a minister.

Adams was devout — he would never have approved a Constitution that separated church and state, as Massachusetts was a theocracy.

Remember too that, in 1787, all the colonies had their own official religion. Maryland was Catholic, Pennsylvania Quaker (MA had hung Quakers for merely being in MA a century earlier). Initially, the fear was that the Federalists would force all the other states to become Puritans, and then with the defeat of the Federalists, that the Jeffersonians would come in and abolish the established Puritan churches in New England. (This was the sort of thing that happened in Europe, notably in what is now Germany.)

What Jefferson should have said is that religion is a state issue that the Federal Government has no control over and stopped there.

People need to remember that none of the Bill of Rights applied to the states until the passage of the 14th Amendment, with the US Supreme Court then “incorporating” various Amendments (most recently the 2nd) as applying to the states because of the 14th’s reference to what the states are not allowed to do.

Yes, I think that separation of church and state is a good thing — but to think it mandated by the 1st Amendment or a letter from Jefferson is asinine. Disestablishmentarianism was a *state* movement.

Even in excellent public schools in Connecticut, I was not taught about the absolutely crucial role of Christianity in shaping the US government and history. It was not until graduate school and a course called “The Historiography of Anglo-American Evangelicalism” that I learned the truth. Attending a homeschooler convention, I learned that “nine out of thirteen states had some sort of religious test requirement for officeholders in their constitutions” https://csac.history.wisc.edu/document-collections/religion-and-the-ratification/religious-test-clause/religious-tests-and-oaths-in-state-constitutions-1776-1784/

Carolyn, look into the First Great Awakening which preceded the American Revolution and set a lot of the philosophical basis for it. Also look into Locke’s concept of God-given rights to life, liberty, and property — that became Jefferson’s life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. Jefferson changed it because “property” had two meanings then, much as “man” does today — this was the era of property requirements for voting.

This is a very tough issue. I think Jefferson saw the end of the confessional state as one of his greatest achievements in VA. The struggle against the Anglicans was perhaps his most difficult. On the other hand, the idea that Democracy is viable without Christian morality strikes me as a very tenuous position. Even in the most pragmatic terms, how can I honestly conduct political discourse or even take the risk of changing parties without a strong ethic of forgiveness closeby?

Eric — how do you balance that against the things that (memory is) Jefferson wrote in his diary about the churches “lying open” (i.e. abandoned) as the people of Virginia fell away from their religion?

Is it that Jefferson won a battle of separation against the Anglicans, or that the people themselves fell away from the Anglicans, thus weakening their political power?

Remember too that the Anglican faith was that of King George — this was definitely an issue in New England in the runup to the Revolution where there long was a conflict between the Puritan (Congregational) faith and the Anglican faith.