Dedicated to my father, Lee, on his 96th birthday—my first philosophy teacher

“By speculating upon causes, we could solve no difficulty about origin and purpose. Our real business is to analyze accurately the circumstances of phenomena, and to connect them by the natural relations of succession and resemblance.” Comte, Positive Philosophy (tr. Martineau, 1858)

“Most of the errors in certain subjects spring from an almost instinctive attempt to gloss over and disguise a particular discontinuity in the nature of reality.” T.E. Hulme, Speculations

The purpose of this essay is to point out one way that philosophy can have practical benefits in how we can think more clearly about problems and how we can solve them. Modern management methods that use facts, data, and statistical control, for example, owe many of their conceptual origins to a somewhat forgotten French philosopher, Auguste Comte. His system, while integrating knowledge across disciplines, did not undermine the philosophical integrity of the humanities. In fact, it may serve as a model for both philosophy and education.

Today, the hundreds of formal academic philosophy departments across our nation’s college and university systems have one thing in common: relevance. That is, how do you define and measure the value and utility of academic philosophy? I don’t mean to ignore or underappreciate the inherent satisfaction and elegance of the philosophic arts; to paraphrase Lupus Servatus, philosophy is valuable for its own sake. Still, it is helpful to think about how the various disciplines are related, how they inform and serve each other, and what imaginative and constructive ways they can be combined to form new knowledge. Philosophic thinking helps us do that.

This sometimes goes by the name of interdisciplinary studies, but that may be too vague. It is often just a way to record and organize university departments that co-list courses or provide some administrative coordination of different subjects in an academic course catalogue—e.g., law and philosophy or computer science and psychology.

Some universities, such as Stanford, have further defined and formalized a coordinated set of department practices. Their symbolic systems program has blended computer science, engineering, psychology, and the fine arts into a novel reordering of the philosophy of mind that has created its own unique demand in business and industry applications. The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign also has a tremendous breadth of blended disciplines that pair its famous engineering programs and the related “positive” sciences with other expressions of intelligence and creativity, including history, music, and business.

Decades ago, British philosopher Karl Popper, who spearheaded a new philosophy of science discipline at the London School of Economics, said that philosophy must be connected to some other tangible activity or inquiry that he called a “vital substrate,” meaning that philosophy by itself could be too abstract and misunderstood, or even incoherent unless it referred to something else that we do. That could include political science and government, but especially history, the physical and biological sciences, mathematics, law, and natural language, and any human activity, including agriculture, architecture, or education.

This brings me to French philosopher Auguste Comte. Why do I bring him up? Because he has a special place in our modern history of thinking, especially in scientific or positive philosophy, that is, using facts and data and organizing them in ways that help us make better decisions. Some might call this rational empiricism, the scientific method, or even an element of modern management science.[1]

I recently discovered a fascinating 1903 translation of University of Paris Professor Lucien Levy-Bruhl’s Philosophy of Auguste Comte. In it, Levy-Bruhl provides an introduction and overview of Comte’s work, which strikes me as generally under-appreciated in how knowledge is created, including the stages it may go through.[2] He is also generally unrecognized as a “father” of management science. Comte is a good example of how philosophy can be directed to what may turn out to be new ways of problem-solving. This is a major issue with our current academic philosophy departments: they aren’t baking any bread; that is, academic philosophy hasn’t produced any new knowledge in decades and, in its current state, doesn’t seem to be organized in ways that can facilitate this.

Part of this challenge is historical: Comte was thinking and writing in a much different time and social stage, and many pressing social problems were attracting the concentration of different disciplines. He was also, of course, part of an extended social and correspondence network of individuals or an “empire of letters.” This is also true of the Chicago pragmatists like Peirce, Mead, Dewey and the influence of William James, who wrote in the later 19th century and during the dynamic 1920s and 30s. One could say that this historical element is also true of the post-war French existentialists. But what can we say about the world of problems that today’s philosophers face? There isn’t much to show from today’s philosophers about any number of problems. This is mainly a result of institutionalism to a degree that did not exist before. Most of us live in and through institutions like university corporations, and these institutions have an incredible web of control and influence over thought and behavior. Even or especially, philosophers who are trained in thinking often have the hardest time thinking independently because they are, first and foremost, of an institution before they are philosophers.

Institutions certainly existed in Comte’s time—and Kant and Hegel’s—and Levy-Bruhl was fully immersed in the university academy. But perhaps it was still a less institutional world, and academic positions were less consolidated across the disciplines, with less influence.

Indeed, some of our greatest philosophers, such as Nietzsche and Wittgenstein, were alienated by institutions, and part of their genius stemmed from this alienation. Comte, too, struggled to maintain his stability, relying on his wife—much like Nietzsche relied on his sister—as his primary stabilizing force rather than on an institution. Both Jung and Freud experienced a similar hostile dissociation, even from the institutions of their own fields. However, personal friendships provided the stabilizing center of gravity in their lives, as was the case with Comte and his relationship with John Stuart Mill. Interestingly, this included a deep, natural rejection or suspicion of the forces of the state. In contrast, today’s academic philosophers are almost entirely absorbed into the modern political state, which may help explain why academic philosophy is relatively inert. There are no major problems being tackled and solved in a truly independent, individual manner that also draws on experience.

So, what can Comte do for us today? A couple of things.

He was able to organize the structure of how knowledge develops in stages and, indeed, how society itself develops in stages of growth—his “law of three stages.”[3] He also helped to organize, at just the right time as far as fundamental science and technology is concerned, a framework of positivism, which has long affected the economic sciences and, ultimately, theories of management. This eventually developed into measuring business performance and testing ideas statistically.

A key takeaway I’d like to make, therefore, is that a philosopher named Auguste Comte provided not only a theory of social development—some say sociology itself—but an organized way of looking at problems more rationally.

A new and very serious problem for philosophers today is understanding how and why rational empiricism and Comte’s philosophy of positivism have systematically broken down in our universities over the past several years. This breakdown has allowed a highly systematic irrationalism and ideological consensus to take hold of many university departments and schools, including their administration and governance. Most fundamentally, it is crucial to explore how ideological beliefs—such as those concerning climate change, geoengineering, terrorism, theories of race, and biomedical technocracy—persist without applying fundamental tests of significance using facts and data. It is a fascinating question whether philosophers like Comte, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, as well as Aristotle, Newton, Leibniz, Whitehead, Russell, Locke, or Emerson, would recognize modern philosophy and modern philosophers as fearlessly probative, perceptively rational, intuitive, and ruthlessly independent—or even serious.

Canadian philosopher Nicholas Sparshott wrote a book titled Taking Life Seriously, in which he argues that the Nicomachean Ethics attributed to Aristotle is a systematic argument—a “chain of reasoned exposition on the problems of human life.” It might be difficult to find a modern-day philosopher in our university departments with such an interest or capacity. In a sense, philosophy appears to be regressing, moving in the reverse order of Comte’s law of stages: first abandoning reason, then misunderstanding metaphysics entirely, and becoming settled finally in a corrupted, effectively pre-theological stage characterized by superstition, idolatry, and political primitivism.

This may all mean that a rational, pragmatic American philosophy is timely and relevant, especially if it provides a theory of conduct within institutional settings, including the university system itself.

[1] Comte’s general philosophy of science, with its focus on the quantitative and mathematical, is central to today’s culture of analysis in our business schools, including quantitative statistical control. He could also be credited with providing a philosophical basis for thinking about how theory and applications work together. An example is Total Quality Management (TQM) and Continuous Quality Improvement, where we consider a continuous cycle of theory and practice through a repetitive process of constant improvement. This has a lot to do with the idea of efficiency, by reduction in cost and waste. This is an underutilized, or often entirely neglected management philosophy in higher education administration. See also A. Cornelius Benjamin, Professor of Philosophy, University of Chicago, and his excellent An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science (1937).

[2] One might argue that the philosophic concept of absolute idealism seeks to effectively integrate Comte’s three stages—namely, the theological, metaphysical, and positive—at least in some intellectual dimension. Of course, if there were a grand “unified” theory of philosophy, it would include at least these three categories. Interestingly, Comte’s admiration for the Catholicism of the Middle Ages, which he called “that masterpiece of political wisdom,” prioritized the spiritual over the temporal, which he argued Protestantism then upended throughout Europe.

[3] The so-called “law of three stages” is articulated in Comte’s The Course of Positive Philosophy. He asserts that society as a whole, and specific sciences, develop through three mentally organized stages: the theological, metaphysical, and positive. A hundred years later, economist W.W. Rostow, at the University of Texas at Austin, drew some inspiration from Comte’s theory in his Economic Stages of Growth, concerning a general pattern of economic and social change.

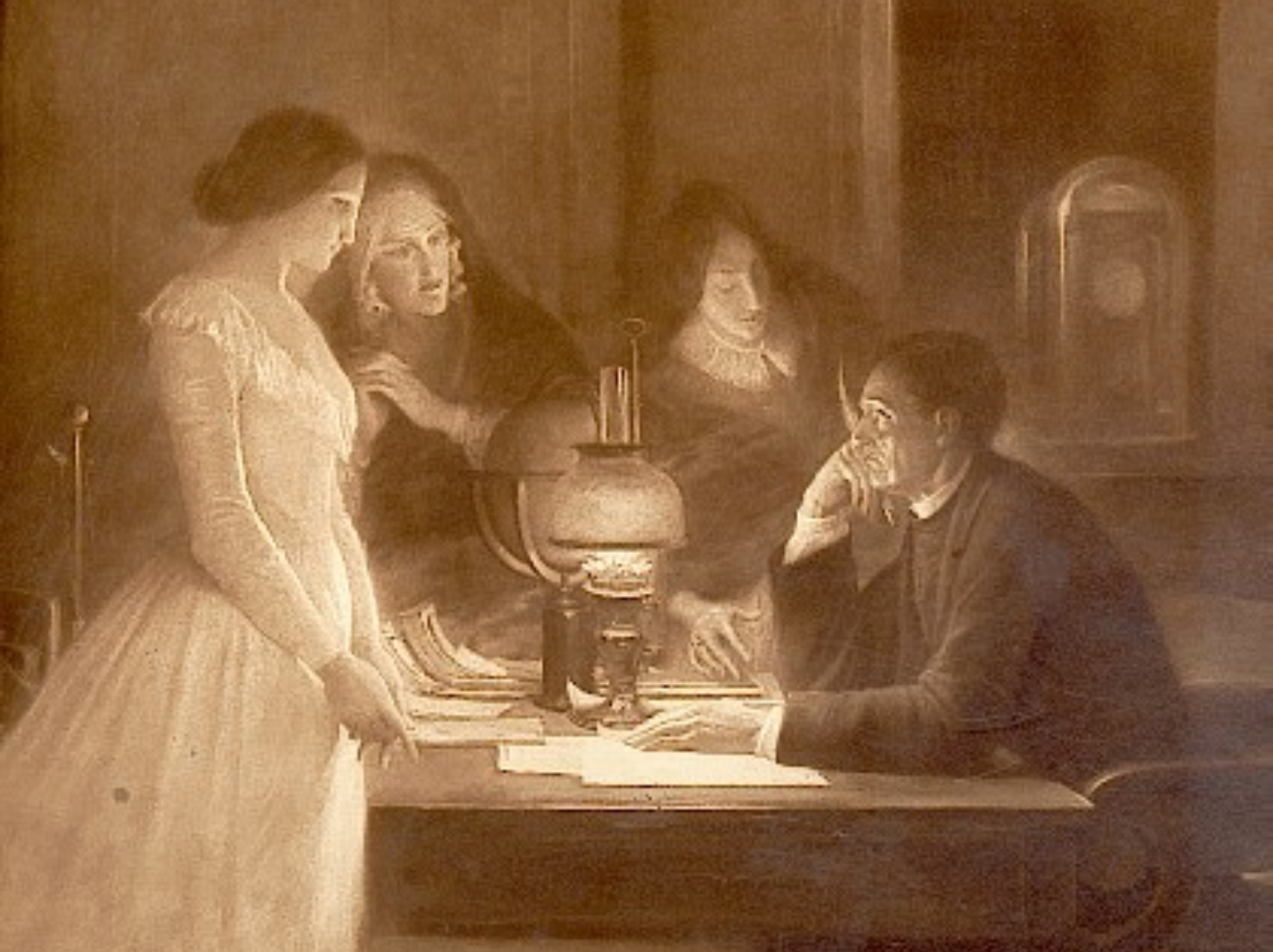

Image by David Labreure — Auguste Comte and His Three Angels: Clotilde de Vaux, Rosalie Boyer, Sophie Bliaux — Wikimedia Commons

“the dynamic 1920s and 30s”

That’s not the term I would use, definitely not in Europe and probably not in the US either.

Yes, we have the hindsight of history, we actually KNOW what things in Germany and Japan would lead to, but there already was the writing on the wall as the Weimar Republic imploded and the Japanese started to march.