In a bizarre incident in California, a seven-year-old girl found herself banned from drawing, suspended from recess for two weeks, and forced to apologize after presenting a drawing to a black classmate. What sparked such controversy? In her colorful creation, she boldly wrote “Black Lives Mater [sic]” (BLM) at the top and, beneath it, sketched four circles to represent herself and her friends holding hands, with the added note “any life.”

She drew this following instruction about Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement, where the child learned about BLM for the first time. Thinking of her black schoolmate, she believed the drawing would make her friend feel welcome.

The parents of the black student saw this very differently. They complained, and the events that followed sparked a lawsuit that is likely on its way to the Supreme Court, with many now debating whether a seven-year-old has a right to free speech and freedom from compelled speech.

What is going underreported in this incident are the psychological effects of public shaming and adult catastrophizing, likely to haunt these children and their classmates for many years to come. If these lessons in black history were intended to foster better relationships between races, it’s hard to miss the irony.

The effects of public shaming on children are well-known in psychology. One can only imagine how confusing it must be to the child when they are shamed for a friendly gesture or for her classmates to witness a peer being resoundingly punished for drawing the wrong thing. Her social standing may never recover.

One would think the important voices in psychology would speak out to address these damaging actions. The sad fact, however, is that the major professional organizations in psychology wildly support this type of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) enforcement.

As long as that remains true, it is virtually assured that similar situations will continue for some time. So what are we to do about this?

For psychology to reclaim its role of providing valuable information on mind and behavior there are two discernable paths: fixing the current system and creating a new system.

To begin down either trail requires some soul-searching. The fields must be reoriented to an objective that makes sense and is, on some level, achievable.

When it comes to scientific research, the goal should always be truth. However skewed our perspectives are from objectivity, only by reaching toward objective truth through formal logic and systematic inquiry can we uncover information that allows us to make better decisions about where to go next. Reorienting back to the goal of finding objective truth in ways that can be replicated is the only way for psychology to regain its credibility as a science.

Postmodern paradigms for research may be ascetically interesting, but they do not provide valid data that can be replicated. Like any other anecdote, lived experiences are not evidence. To be functional, science must generate valid evidence and follow it.

The goals of psychotherapy are more complex. While the medical field can easily point to whether a disease is cured or mitigated, it is much more difficult to make those determinations about many issues in mental health.

Conditions like depression or anxiety, for example, may be adaptive responses to bad circumstances. In such cases, it would make more sense to help a client get a job or improve their education than receive a talking cure that, by its nature, is better suited to addressing situations where the causes of such mental health issues are embedded in self-destructive behavior or are otherwise difficult to identify.

Advocacy is attractive to therapy practitioners because of the seemingly obvious situational causes of mental health conditions. However, as the complexity of culture and the systemic structure of society make it impossible to predict what socio-political tinkering would have productive outcomes, therapy professions should avoid political advocacy on ethical grounds.

We have certainly seen the destructive effects of practitioners trying to push societal change for their versions of a greater good in eugenics, gender, and DEI initiatives.

Then, better client triage would make more sense, where those who would be best served by social workers, employment, community groups, educational opportunities, or occupational therapy are connected with those outlets.

Talk therapy would be reserved for those clients who primarily need emotional support, or have conditions characterized by delusions, emotional dysregulation, or other non-adaptive psychological responses.

When the psychotherapy clientele is more clearly established, it is easier to consider appropriate goals for treatment within our culture. Thus, a goal of using the applied knowledge from psychology in psychotherapy should be to mitigate symptoms and improve client well-being.

While this may seem like a redundant throwback to the stated goal of therapy in recent years, in a world where practitioners are doing media victory laps touting how therapy must be politicized despite politicization in therapy being unethical, it bears the repetition.

This goal for applying psychology’s would ideally inform the direction of research to better understand what humans need to flourish and what interventions are most effective for various conditions. As such, in-depth research into supertherapists, for example, is long overdue.

Two decades of research must be sorted for what bears replication and what is self-promoting garbage.

This would only address a portion of the issues currently plaguing the field. Returning to former best practices is merely a first step. Since therapy diagnosis and treatment must be considered within a cultural context—where, for example, seeing visions might be pathologized in the U.S. but seen as normal in other cultures—the greater challenge lies in reaching consensus on which cultural norms, such as those related to gender, we are willing to tolerate.

The sooner we can settle those questions, the better. Millions of seven-year-olds who want to draw pictures for their friends are waiting.

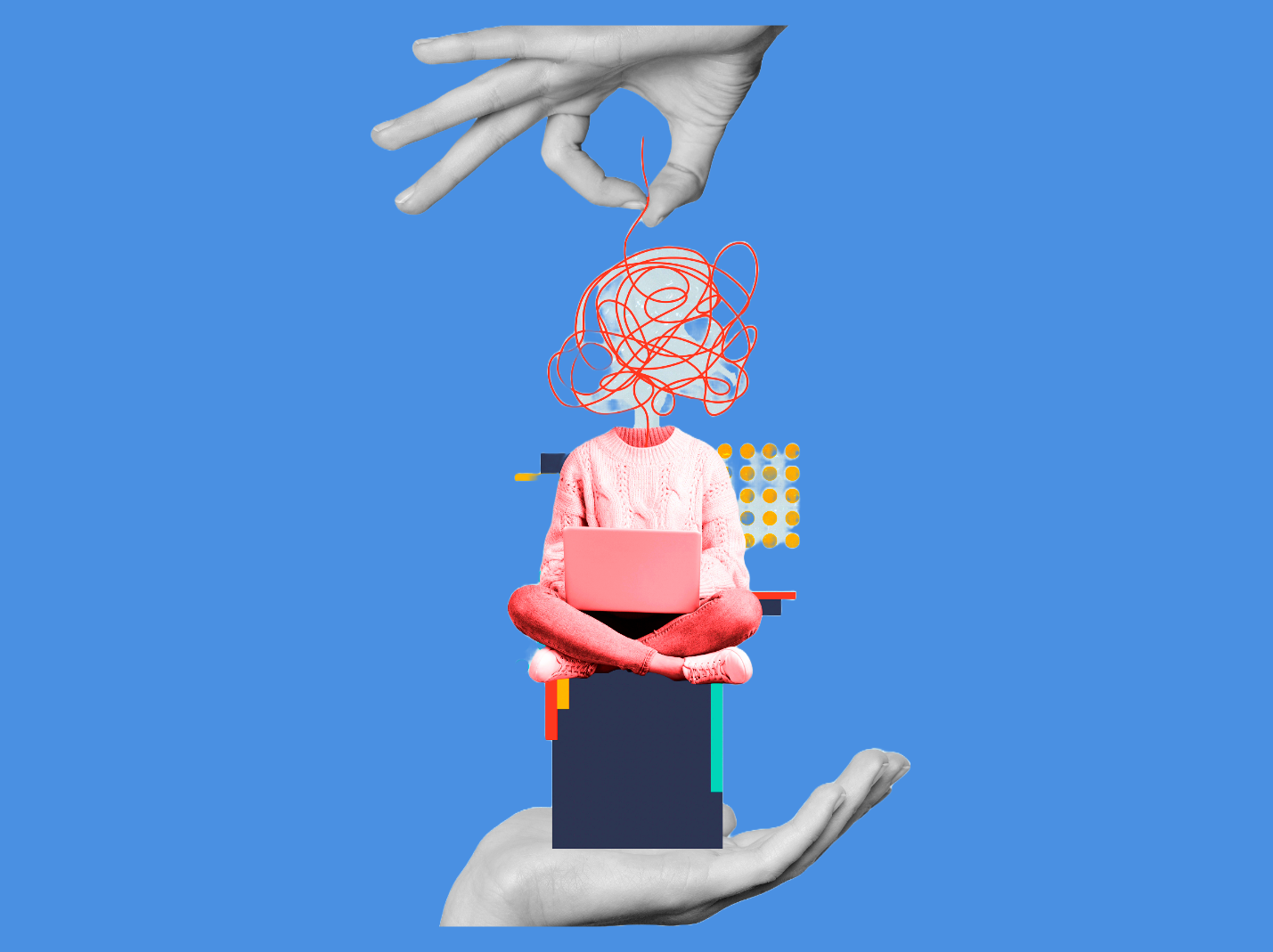

Image designed by Jared Gould using art by deagreez on Adobe Stock, Asset ID#: 632895812

What the Voodoo Scientists don’t realize is that they’ve created a family of racists that otherwise would not have existed.

That little girl had Black friends — after her family having been forced to move 3000+ miles away from the world she had always known, I doubt that she does now. Nor her siblings. And I don’t want to think what her parents now think of Blacks….