“Everything goes when anything goes all of the time.”

—Paul Westerberg

Alexis de Tocqueville noted in Democracy in America (1835/40) that upon the advent of written constitutions and electoral politics, the aristocracies of the Western world had to rediscover their purpose. He saw the United States as the most acute example of a society in which the contrarian skills, powers, and attitudes of a caste of nobles—useful in the old medieval regime—had been eclipsed by egalitarianism. But this eclipse, or transit, as it were, created the need for new brakes against the tyrannical tendencies of governments and the misguided urges of the masses. Tocqueville spent hundreds of pages reviewing possible sources of resistance. Lawyers, women, artists, soldiers, entrepreneurs, and religious leaders would all be called upon to push back against the self-centered madness of the mob and its populist leaders.

The French count argued that because people in aristocracies had fixed places in their social hierarchies, they didn’t suffer as much from the urge to conform to the values of everyone else around them. A carpenter, lieutenant, merchant, friar, or marquise might look to his colleagues for how to think and behave, but it made no sense for him to imitate other groups to which he would never belong. Thus, Tocqueville unveiled a critical paradox: by eliminating castes, modern democracy unleashes the tyranny of public opinion. And that opinion is how fanatical egalitarianism threatens personal liberty. By implication, a one-off vote to install a despotic regime in a fake democracy like Russia, China, or Cuba reflects already flawed social conditions. Such regimes are tragic but predictable. Far more worrisome is that even a mature democracy—one that defends liberty in its laws and constitutions—tends to repress individuality. It’s just that the mechanisms are more subtle; they’re social and habitual rather than legal or authoritarian. And their lack of visibility is what makes them so sinister. They often cloak themselves in the rhetoric and symbols of freedom, democracy, and the public good.

The pressure to conform to the juvenile morality of the masses is not new. It’s the stuff of political nightmares from Thucydides and Tacitus to Ortega and Orwell.

Echoing Burke and Jefferson—and anticipating Mill—Tocqueville’s book remains the most detailed and wide-ranging assessment of the risks that democracy poses to the personal liberty previously defended by self-interested aristocratic elites. The issue is magnified in nations where democracy achieves cult-like status. I call such countries “hyper democracies” because they suffer from excess idealism regarding equality.

Today, citizens in the U.S., Canada, England, France, and Spain are blind to the dangers of conformism because they instinctively deem its antidotes undemocratic and immoral. To them, it seems paradoxical and irrational that democracy needs checks because otherwise it short-circuits itself and turns into the very tyranny it despises.

Within thriving and stable democratic nations there’s an even more subtle structural threat related to wealth and technological success. Tocqueville touches on this, but readers tend to miss it. Recent experience has shown that a problem with the newly baptized aristocratic elites of a powerful democracy like the U.S. is their susceptibility to “career capture.” This mimics how politicians use “regulatory capture” to extract money and obedience from corporations and professional associations. By forming a committee to regulate some part of the economy, such organizations emerge from the woodwork and do whatever it takes to preserve their power and prestige. They’re induced to lobby the committee and bribe its members with campaign funds.

To maintain their status and income, most individuals behave just like those corporations and associations. Indeed, “career capture” is the deeper cause of “regulatory capture.” And can we blame them? I’m not so sure anymore. Whose baby doesn’t need a new pair of shoes?

So, when governments and political activists take over media platforms, high-profile businesses, universities, colleges, and clubs, the elites that populate such institutions can’t help but embrace the new ideology being foisted on them. The stakes are too high. The owners and managers of multibillion-dollar companies, the administrators and professors at Ivy League universities, the scientists and doctors who’ve spent fifteen years of their lives obtaining credentials, licenses, and grants—such people aren’t likely to think independently or take stands on principle. The same difficulty infects government agencies. How long and how much training, certification, and ass-kissing does it take to climb to the top of the Central Intelligence Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Centers for Disease Control, or Secret Service? Is it any wonder these are now the most corrupt agencies on the planet?

We have an anatomy of the decay of an aging democratic nation. Conforming to incompetence and corruption gets normalized when a society and its government are blessed—or plagued—by the large and successful institutions that make their individual members powerful and wealthy. Such organizations depend on an internally perverted “network of mistrust” based on everyone’s shared fear of the honesty and morality that might bring serious reform. This is because good people expose the perils of groupthink, thereby destroying the political, cultural, and professional capital that everyone else has worked so long to accumulate. Thus, institutions promote complicity in their own abuses. Such complicity is both mutually recognized and unconscious.

This thesis was advanced by the now rightly fashionable economic theorist Ludwig von Mises. In one of his lesser-known books—Socialism (1922)—he described how the more socialist a nation becomes, the more a desire for political conformity replaces merit, ability, and work to attain wealth and power. And the process is reciprocal: the more a nation requires political conformity from its citizens, the more it transforms into a socialist nightmare.

In this light, a dysfunctional bureaucracy is the essence of socialism, and vice versa.

Large institutions and collectivist ideologies work together. Even libertarians forget that this moral case for antitrust legislation cannot be held apart from the case for efficiency. Without competition, institutions will become dystopian and immoral. By contrast, an anti-institutional morality provides a kind of efficiency. Modern America is a kakistocracy due of the tyranny of political correctness and language policing that took hold in the 1970s.

Spy agencies, health departments, national police forces, and government attorneys have become so powerful that they routinely destroy their political enemies by framing them, arresting them, and suing them into submission. Educational institutions, large corporations, and professional organizations provide a supporting network of social conditions and ideologies for our government masters with whom they share their values even as they fear their wrath. Cancel culture and wokeness—new versions of political correctness—thrive in this atmosphere.

Louis XIV paved the way for something similar by centralizing power in France at the end of the seventeenth century. He domesticated French aristocrats by ordering them to live at Versailles and turning them into helpless patrons. Napoleons I and III were inevitable outcomes. Today, in the U.S., our natural replacements for the English aristocracy against which we once rebelled have been recaptured by our central government. We have met the enemy, and it is us.

This is why U.S. elites must be chastened with a rigorous brand of populist idealism, and often. It’s also why we’re back to a Tocquevillian paradox. This particular type of populism is the essence of American honor and patriotism. It’s unlike European nationalism, which is often driven by ethnic pride. Rather, it’s supposed to be based on the idea of personal freedom as the negation of government power. Like all democracies, America requires political parties. The difference is that in America, one party must be the anti-bureaucracy party, the anti-socialist party.

Politics must decentralize power. Otherwise, corruption will prevail, and personal freedom will die. When that happens in a country as powerful as the U.S., the effects can be global and devastating.

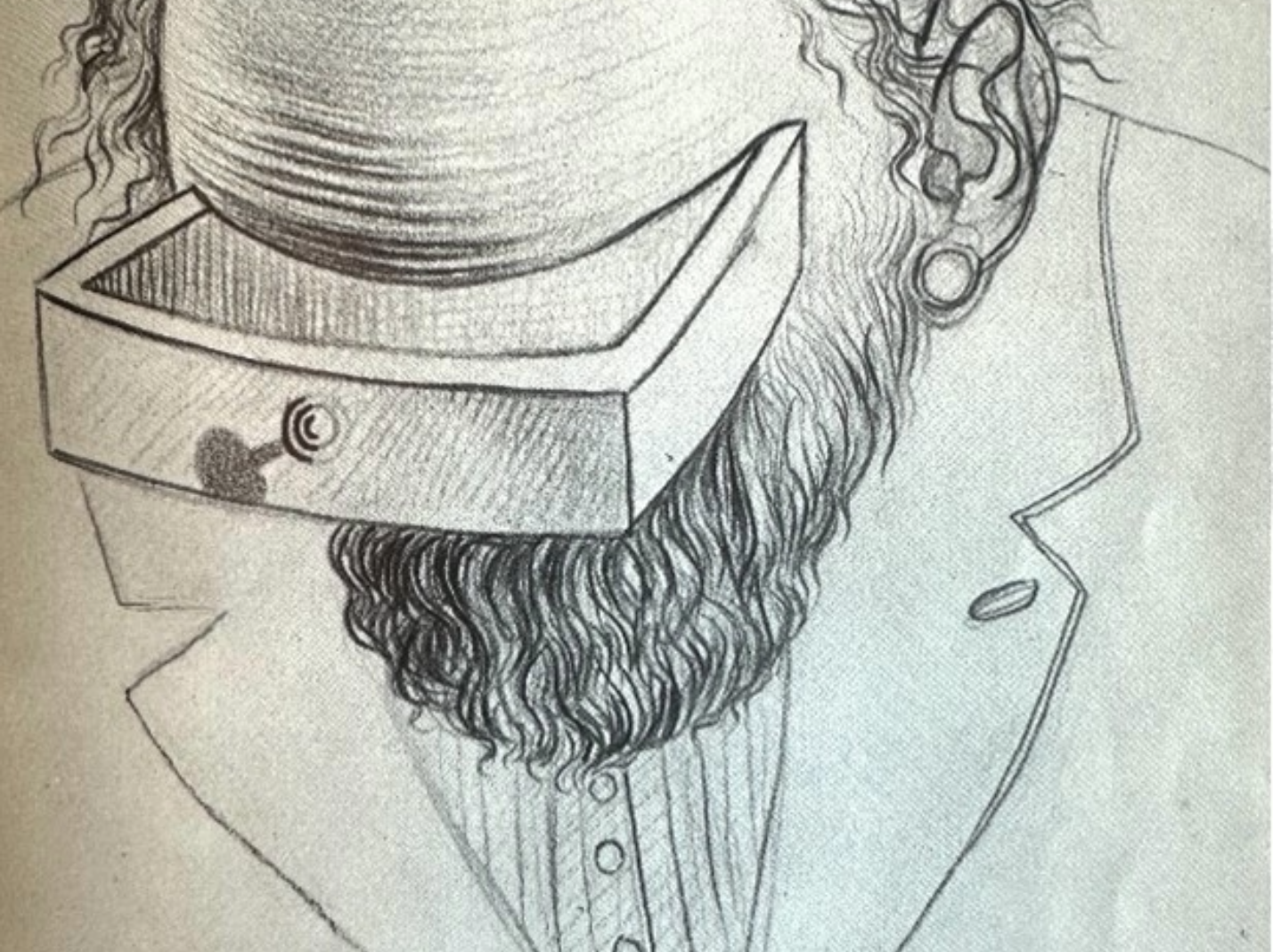

Image by Salvador Dalí, Freudian Portrait of a Bureaucrat (1936)

Would it be fair to say that 2008 is your departure date for our dysfunctional bureaucracy with its attendant socialism? OK. I was watching it from the trading floor. It sure looked like a giant orchestrated game after Lehman went. But I sensed something in academia about twenty years before that (a departure date for that might be 1968). But I’m also sensing some general law. As if American is finally becoming Europe. Our hyper democratic society by its nature generates and then overpopulates such institutions as place holders. And the elite, but talentless, mentalities it produces, the ones that go in and out of government and business, are remarkably pernicious of late.

The author writes:

>

This mimics how politicians use “regulatory capture” to extract money and obedience from corporations and professional associations.

<

The term "regulatory capture" is actually defined as the tendency for large corporations and professional associations to take over governmental entities designed to regulate them and ensure policies to their liking. One technique is to simply hire governmental regulators to work for them after a period of making pro-industry decisions. Politicians, also, tend to make decisions favoring private industry that provides the politicians with campaign contributions or employment opportunities. In the aughts it was common for Republican caucus members to hold a farewell party for those members leaving to become lobbyists–it was seen as a promotion.

The point is it is almost always private industry (or professional organizations) that get their way. DeSantis challenged Disney but Disney essentially won. The AMA still restricts competition as they (through a shell organization) determine medical school admission sizes and residency slots. This is not the tail wagging the dog–rather, the dog is fully in control.

Fair enough. And thanks for the correction. Still kind of a “the chicken or the egg” thing in my view. But I can handle it. The career, and from there, the institutional capture are still driving the souls of all involved, private corporations or government regulators. Hopefully more efficient corporations and reformist politicians can still take out the trash now and again. I’m not holding my breath. Something seems massively broken.

My take is slightly different — throughout American history, and through the 1930s, family fortunes were LOST as well as won. This was happening prior to the American Revolution and a lot of the British stupidity at the time needs to be viewed as an attempt to maintain their social privilege in an era of a changing economic order.

I don’t know what the government did in response to the 1987 stock market crash, nor the DotCom crash fifteen years later — but we all know the massive Federal bailouts in response to the problems of 2008-2010. In an earlier era, that wouldn’t have happened — the banks and insurance companies *would have* failed, with the subsequent consequences but also the opportunities for others that were created in the process.

Likewise, the GM retirees would have lost both their pensions and gold-plated (non-Medicare) health plans — but that money would have gone to finance better and cheaper American built cars. This has happened in the past — Dodge became part of Chrysler when the Dodge brothers died in the 1918 flu epidemic, all of the divisions of GM had been independent auto manufacturers, with both Studebaker, Packard, and other collapsing outright.

Studebaker had left threaded lug nuts on the right side of the vehicle which actually was a good idea from the engineering standpoint, the rotation wouldn’t loosen them, but a lot of people (including me) didn’t know that and sheared them off trying to loosen them by turning the wrench to the left. But I digress….

Other than with immigrants, we really haven’t had any upward social mobility in the past 60 years and no small part of that has been governmental intervention to prevent those on the top from falling. THAT, more than anything else, is what has lead to political conformity replacing merit, ability, and work to attain wealth and power.

The trauma of 2008 would have been extreme without government bailouts, but 16 years later, we would have recovered — and no one is telling who is going to pay the ultimate debt from that. Or the other governmental largess….

The Amherst College yearbooks from the early 1930s list the names and addresses of class members who had to drop out “because of the economic situation.” These lists were not insignificant — it was a different time back then and I think the mistake is in not realizing that.