At an exhilarating four-hand piano house concert in Tucson, two noted recording and performing artists, Dana Muller and Gary Steigerwalt, played a signature piece by Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937), La Valse: Poème Chorégraphique composed in 1919-1920. Later, in a discussion with the audience, the pianists noted that they followed the faster tempo set by the Orchestre National de France under the baton of Leonard Bernstein. But it was clear, listening to the four-hand piano music, that Ravel’s piece was far more than an aggressive tempo. Ravel had a powerful message to convey: that despite war, the human spirit would prevail.

Ravel first depicted in La Valse, like a distant memory, the bright optimism of the high Viennese culture of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with formal balls and the 3/4-time waltz which Strauss made famous.

But he had to live with another disappointing reality that forever changed his world.

World War I tragically destroyed lives, families, and communities, ended empires, subjected many people to the trauma of bombs, poison gas, and gunfire, and cast a dark, threatening shadow over humanity for years to come. In fact, Ravel would not live to see that only two years after his death, another war came…Soon the megalomaniac Hitler would attempt to impose the Nazi agenda on the world.

How could Maurice Ravel’s compositions be the same after “the War to End All Wars?” His La Valse says it all.

You hear the bombs, the despair, the excruciating torment, the hurt and pain, the grief and sorrow of death. Yet the human spirit persists in breaking through with beauty and greater power than the destructive darkness. There is the grace of truth, hope, and love that symbolically holds onto the waltz as the symbol of recovery for all that is good. All can be heard if it were a complex but dynamic tableau: while the glass breaks, the symbol persists. Beginning with doubt and uncertainty, it concludes triumphantly, striking a chord instantly with audiences who absorb its passionate emotion enthusiastically, especially when, as here, so ably communicated by the artists.

Remarkably, a similar composer’s heartache about the tragedy of war has been depicted in the work of a contemporary composer, Lewis Spratlan, entitled Dreams of a Madman: Hitler, also a work for four-hand piano. Spratlan is unsparing in his depiction of the violence of World War II. One feels the horror of war and the mindset bent on destruction in his piece, featured on the CD recording by Muller and Steigerwalt, In Your Head: New Music for Piano Four Hands (2018, Navona Records, NV6190).

Another important contemporary composer, Daniel Asia, in his Symphony No. 5, uses the sharp strokes of strings, the drum of a timpani, and the poignant harmony of winds to depict the sorrow of war. He takes a lyrical text from a poem about a soldier by Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai. An excerpt:

Like torn shirts that my mother couldn’t mend, the dead are strewn about the world.

Like them, we’ll never love or know what voices weep and winds will pass by to say Amen.

Asia concludes with a Hebrew prayer, Baruch Adonai L’Olam. What else can a human do in the face of such enigmas and mysteries? How will the resolution come, but not for a divine intervention? The gentle heartfelt choral melody agonizingly raises the anguish into a crescendo toward heaven. Then, there is mostly silence, with only the voice of an oboe to suggest that there is something not nothing, and that is something to hang onto and be hopeful about since, without divine revelation, we do not know why there is something rather than nothing.

But war persisted in Europe during the nineteenth century. Ludwig van Beethoven may have composed his dramatic and militaristic Third Piano Concerto to honor Napoleon’s rise as a political figure. Did Beethoven believe that Napoleon’s victory over the Austrians in 1796 deserved commemoration with a piece that bridged classical form with a new expressive form? Had the world changed for the better?

For the German Beethoven, the French Napoleon initially gave him hope that order in Europe would follow a period of terribly bloody and vengeful revolutionary disorder. Yet Beethoven followed his third piano concerto four years later (1804) with his Third Symphony (Eroica), where he scratched out the dedication to Napoleon Bonaparte, allegedly after hearing the disappointing and disillusioning news that Napoleon had undemocratically crowned himself a dictator as Emperor of France.

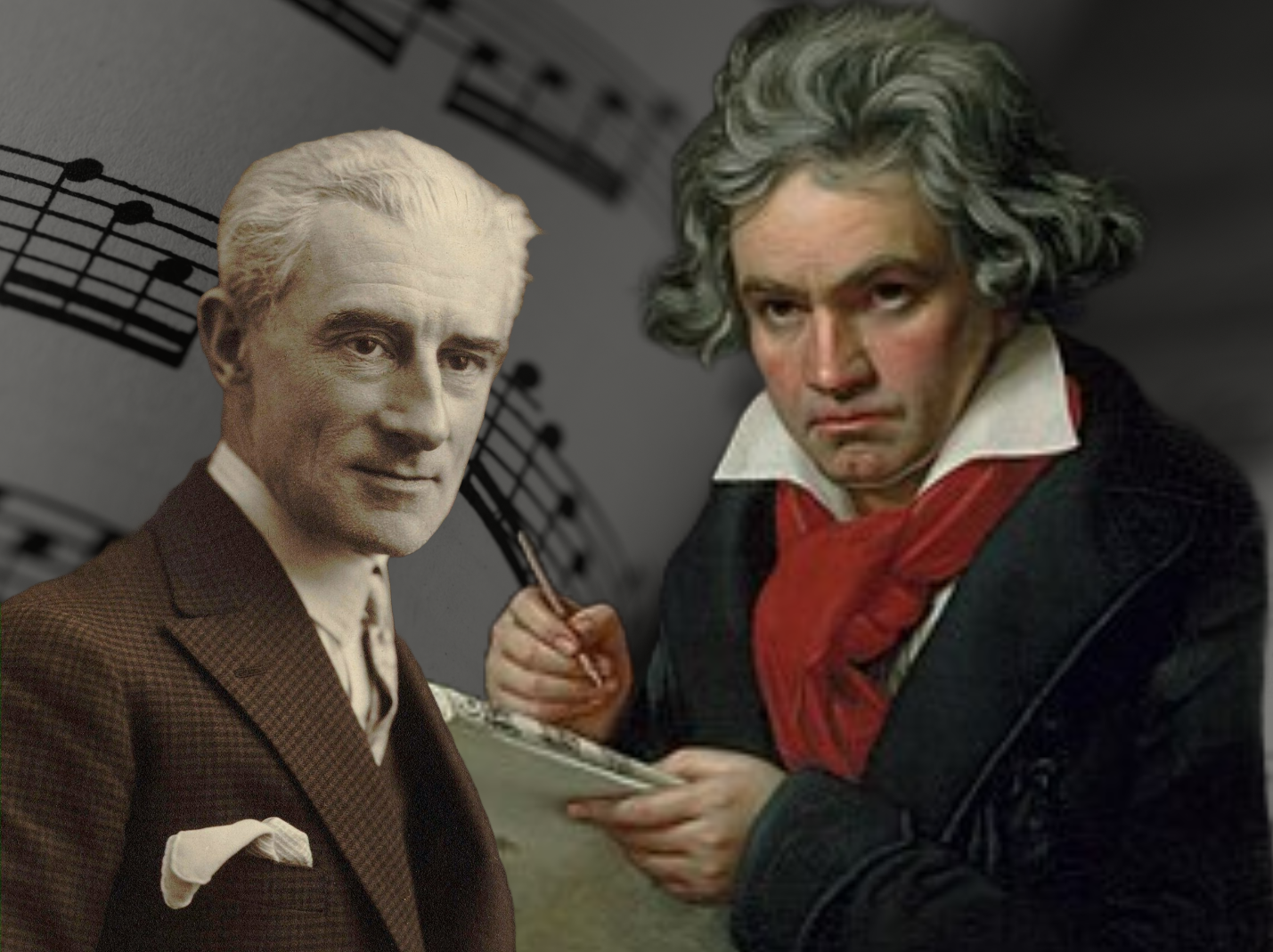

These stories suggest that composers know they share prominent intellectual space with their predecessors, who likewise sought to address big and important—but necessarily recurring—subjects. Beethoven introduced the Romantic Age with masterpieces that provided beautiful lyrical passages of hope and light within a framework of dark tones of conflict. His example is noted, if not followed, by composers of later generations who face and continue to face similar political problems when tyranny and oppression threaten to disturb good order.

Images of Beethoven and Ravel from Wikimedia Commons & Background is angelo.gi — Adobe Stock — Asset ID#: 122023645 & Edited by Jared Gould

Let me add that Ravel honored the lives of friends of his killed during the war in his Le Tombeau de Couperin.

The strife and misery caused by governments has indeed inspired many composers.