Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by RealClear Wire on June 13, 2024. It is crossposted here with permission.

William Carney heard a familiar voice roar, “Forward 54th!” Dashing up a steep slope with sand chafing his arms, legs, and neck, he saw a bullet-ridden flag flutter, beginning an agonizing plummet to the ground.

He must save the colors; he must save the colors. Throwing his rifle aside, he grabbed the Stars and Stripes before they landed on the gritty crest. Carney braced himself against the flag, ready to die, while rallying his friends to take Fort Wagner.

Despite the danger around him, Sgt. William H. Carney of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment survived, holding the flag aloft for an entire half hour on the fort’s parapet.

On Flag Day, Americans honor the sacrifices made by many to safeguard the symbol of our national union. Generations of patriots have hallowed the red, white, and blue. Across the world, it has come to represent freedom from bondage and tyranny.

To understand the flag’s meaning, we can look back at the heroic struggles of one unit of soldiers under it: the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, one of the first Civil War regiments to recruit African Americans.

The 54th was established shortly after President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of Jan. 1, 1863, which announced that black men could enlist in the United States Army and Navy.

The 25-year-old Col. Robert Gould Shaw was commissioned to command the 54th. Born to a well-heeled abolitionist family, Shaw was deeply committed to the cause of freedom.

Shaw drilled his regiment outside of Boston, and on May 28, 1863, they paraded through the city to bid the residents farewell.

The parade passed the home of the famous abolitionist, where William Lloyd Garrison watched them, crying with pride. Spectators thronged the streets of Boston, cheering the men on. At night, they left for the coast of South Carolina.

One of the men who marched in the parade was William Harvey Carney, who enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts in February 1863. Born enslaved in Norfolk, Virginia, on Feb. 29, 1840, Carney eventually found freedom. Then, he wanted to fight for it. Despite his “strong inclination” to join the ministry, he decided to “serve my God by serving my country and my oppressed brothers.”

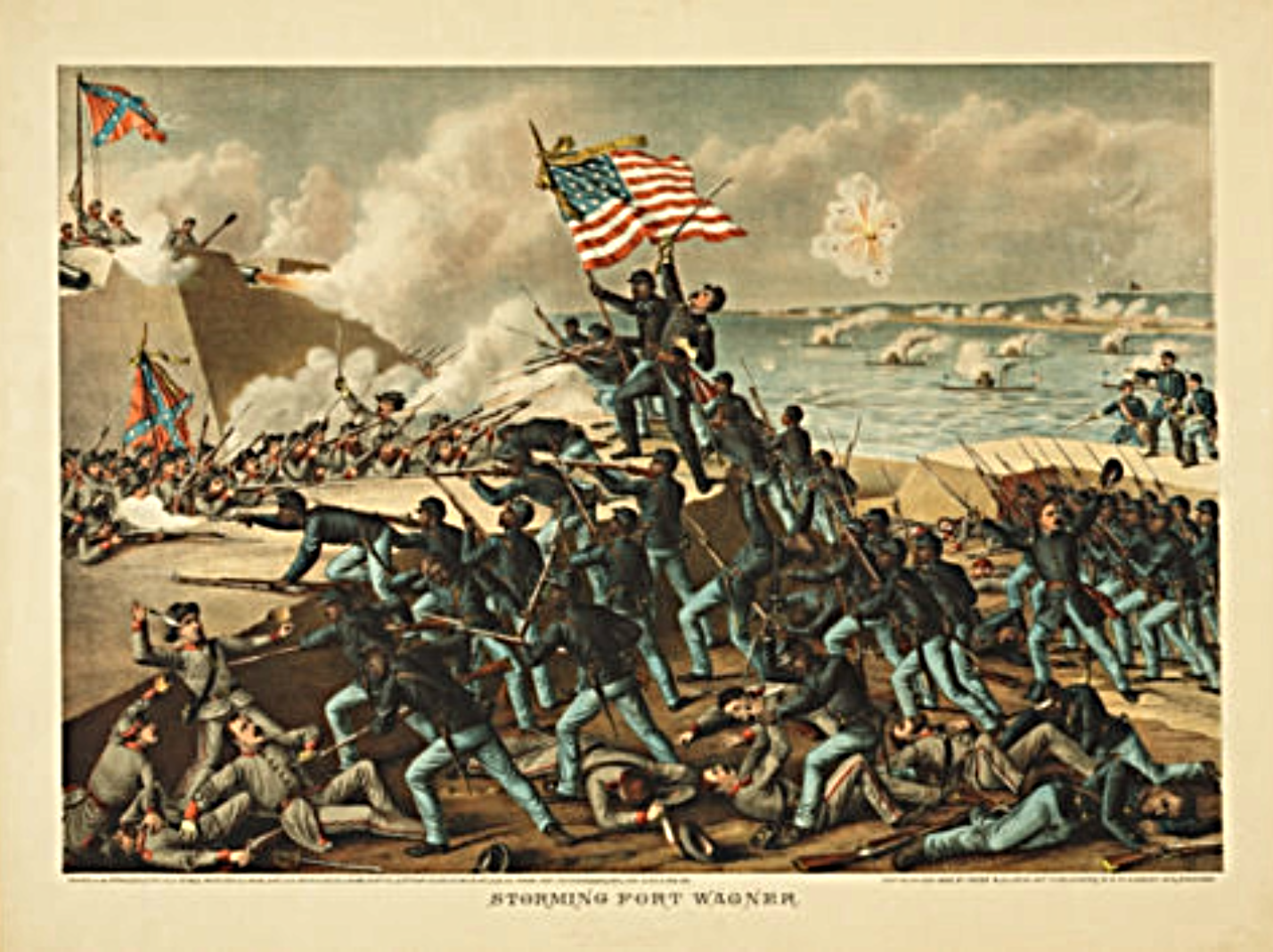

Carney, Shaw, and the rest of the 54th Massachusetts marched to the South in time to participate in the siege of Charleston, the city that many Northerners blamed for starting the Civil War. The infamous Fort Sumter loomed at the mouth of the city’s harbor. Fort Wagner, situated on Morris Island, guarded the southern part of the harbor. When the call was made for Union ground forces to take Fort Wagner at dusk on July 18, the 54th Massachusetts led the way.

One veteran of the battle described the beach in front of Fort Wagner as “the fiery vortex of hell.” The regiment surged through one of the narrowest points on the beach, effectively becoming a spear-shaped mass of men with Col. Shaw and the flagbearer at the tip. Running over the dunes, wading through the moat, and now scaling the sandy ramparts, they watched as Shaw raised his sword atop the fort’s parapet, crying, “Forward 54th!” and met his death in a hail of gunfire.

Carney did not wait to act after Shaw fell. He recovered the flag and held a futile rallying point on the sandy crest of the fort. Two hours later, he limped back to the field hospital. Carney refused to let anyone take the flag from him. Before he fainted from blood loss, Carney told the men around him, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground!”

The Union forces failed to take Fort Wagner that day. The 54th Massachusetts suffered heavy losses during the battle. Many of the survivors captured by the Confederates were given no quarter or sold into slavery. Shaw’s body was tossed into a mass grave alongside the brave black Americans who fought and died with him. Those wounded in the battle evacuated to Beaufort, South Carolina, the next day.

Nobody embodied bravery and patriotism in defense of the American flag more than Sgt. William H. Carney. He was an American whose wartime efforts epitomized the lengths to which one might strive to fulfill America’s founding ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

For Carney’s valorous service to the United States, he became the first black American to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor. Later in life, Carney humbly said: “Boys, I only did my duty. The old flag never touched the ground.”

Photo by Penn State Special Collections — Flickr