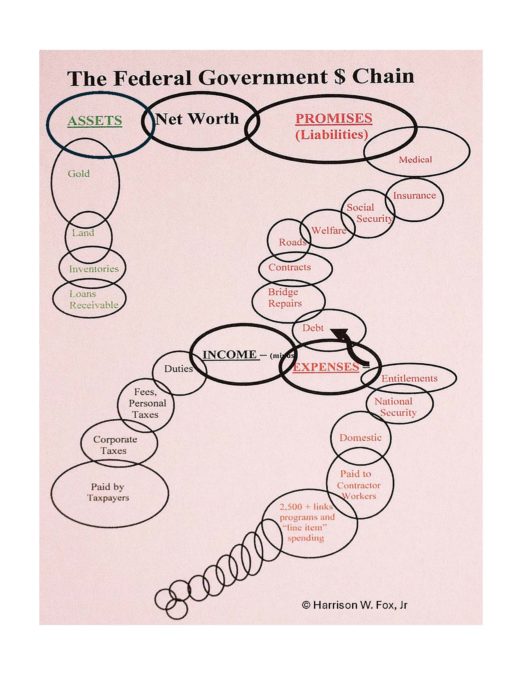

The federal dollar chain is an important civics lesson for college students. It will help answer, “Can I expect to receive Social Security payments? And will the United States of America go bankrupt?” The federal dollar chain is at least seventy-five years long. It is a conceptual tool that begins with taxes paid today by each citizen and continues with Social Security’s promise to the 18-year-old just entering the workforce who will live to be 93 years old. The over 2,500 federal government dollar chain links are critical to each other. Like all chains, it is only as strong as its weakest link. Weak links limit the capability of the federal government to meet needs, pay for promises, and perform at peak efficiency. Knowing the relationships between net worth, assets, promises (liabilities), income (revenues), and expenses (spending) helps explain how governments work.

At the top of the federal dollar chain is the United States’ net worth—the top black link. Net worth is equal to assets minus promises. Attached to the net worth link are assets (green) and promises (red) which are liabilities. The last promise (red) link is debt. Federal debt is a major part of federal government promises. Debt increases or decreases are key to government thrift. A government’s ability to pay for promises can be predicted by how they match up with government assets. If promises exceed assets, debt is created.

The Economist notes the point in history where unease over high levels of government debt began. Since King Edward the Third of England, who defaulted “on his debt to Italian bankers in 1335, international investors have fretted about high levels of government indebtedness.”[1] A recurring theme throughout United States history is that “federal debt should be avoided.” Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, the Populists, Dwight Eisenhower, Ross Perot, and numerous others have decried excess government spending. Ben Franklin, when identifying vices, found, “The second vice is lying; the first is running in debt.”[2]

Ancient Athens suffered, as does the United States, from a “chronic deficiency in revenue.”[3] For Athenians, the difference between surpluses of production minus needs of subsistence was small. Government revenue was hard to collect. There was no concept of an income tax. Athens relied on commodity, property, and indirect taxes. Importantly, there was no notion of deficit spending or national debt. Budgets had to be balanced. State and local governments follow the Athenian balanced budget concept, but the federal government does not.

In the modern era, federal debt has achieved its full potential. The link between net worth, national assets, and promises (liabilities) to spending and revenues is critical in our examination of “true national debt.” America’s “true national debt”—the sum of all federal promises, including our yearly deficits—overwhelms us. Our government should start using a balance sheet to track promises or unfunded liabilities with assets. USA Today and David Walker, Congress’s former Comptroller General, both estimate that federal government unfunded liabilities are more than $60 trillion, some say as much as $130 trillion—not the often quoted is $18 trillion.[4] American citizens are on the hook for at least $200,000 to repay the county’s debt and even more for unfunded obligations such as Social Security, government pensions, and Medicare.

Assets included on the federal balance sheets are government resources that remain available to meet future needs. Federal assets include cash and monetary assets; gold; accounts receivable; inventories; loans receivable; property, plant, and equipment; international organizations investments; deferred retirement costs; financial assets; and the leading asset by far is the power to tax. The value of the power to tax in 2015 dollars is estimated to have increased from $31 trillion in 1955 to $32 trillion in 1955 and $34 trillion by 2015.[5] The 1913 passage of the 16th Amendment to the Constitution greatly enhanced the power to tax. This amendment allowed personal and corporate income progressive taxation. Only the extraordinarily rich were taxed initially. A rate of one percent was imposed on those earning over $3,000. This captured just two percent of wage earners. During World War I, income taxes became mass, not class taxes. Tax rates have ebbed and flowed over the years, with significant tax decreases occurring during the Coolidge, Kennedy, Reagan, and Trump administrations.

Today, over 81 percent of federal revenues come from individuals. Individuals pay income taxes (44 percent) and social insurance tax contributions (37 percent). Corporations pay more than 10 percent. The remaining 9 percent is collected through excise taxes, duties, and other receipts. Individuals, since they pay most of the taxes, deserve a good quality tax law. It should be simple, efficient, neutral, and equitable. Current tax law is rife with complexity, inequities, inefficiencies, bias, and unjustified burdens. Even tax attorneys, who often spend a career studying the tax code, admit that they know little about most of the tax law. One of the primary reasons for a complete overhaul of the tax system is to take the guesswork out of paying taxes. A fair, efficient, neutral, and easy to comply with tax system will collect more taxes. Increasing collections, with spending restraint, should reduce the effective rate that individuals and corporations pay as well as the national debt.

In 1929, federal government spending accounted for three percent of the economy; today, it exceeds 20 percent. Even during the 1930’s depression, federal government expenses averaged just 10 percent of GNP. Federal spending for 2017 was broken down as follows: individuals’, 30 percent; for-profit entities, 19 percent; state and local governments, 7 percent; non-profits and universities, 5 percent; other, 8 percent; and running the government, 21 percent. [6] Hundreds of federal programs overlap, are wasteful, and duplicate state, local, and private efforts. Most alarming is that mandatory entitlements crowd out defense, education, commerce, international, conservation, and stewardship spending.

Today, the federal government’s elected representatives, managers, and citizens focus almost exclusively on current years’ income (revenues) and expenses (outlays), not the long-term consequences of debt. Not enough consideration is given to long-term promises and how they will be paid for. State and local dollar chains are almost as long. Debt is not allowed by these governments. The current federal budget and accounting procedures are antiquated—nobody knows how many federal programs there are. There is no readily available and transparent electronic link between federal spending accounts and how well these programs are performing for citizens or even members of Congress to evaluate. Thus, program failure is difficult to determine.

[1] “Caught in the debt trap,” The Economist, April 1, 1995, page 59.

[2] Benjamin Franklin, The Way to Wealth, i, page 449.

[3] David Stockton, The Classical Athenian Democracy, Oxford University Press, 1990, page 12.

[4] Bradford Richardson, “Ex-GAO head: US debt is three times more than you think,” The Hill, November 7, 2015, Walker explained U.S. Debt to host John Catsimatidis on “The Cats Roundtable” on New York’s AM-970 in an interview.

[5] John Makin, “America’s Fiscal Policy,” American Enterprise Institute Annual Policy Conference, Willard Intercontinental, Washington D.C., December 3-4, 1991, page 55.

[6] Usaspending.gov

Photo by Zimu — Adobe Stock — Asset ID#: 363120226 & Edited by Jared Gould