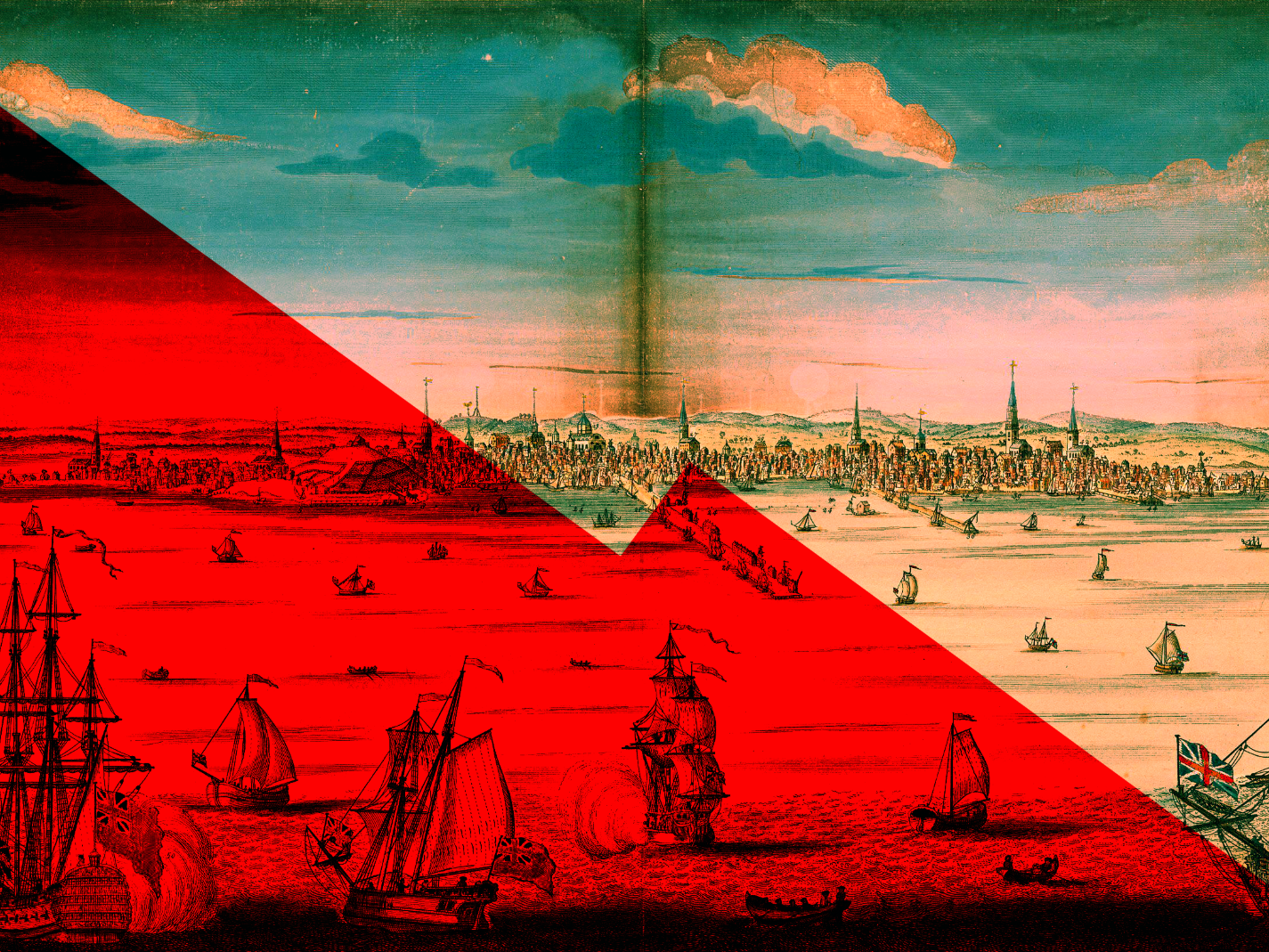

On June 1, 1774, Britain’s Parliament gave assent to the Boston Port Act.

By mandating the complete shutdown of Boston’s port, prohibiting any loading, unloading, or transportation of goods within the town and its harbor, Parliament believed it was sending a powerful signal of its authority to the rebellious Bostonians who had dumped tea into the harbor:

And it is hereby declared and enacted, that nothing herein contained shall extend or be construed, to enable his Majesty to appoint such port, harbour, creeks, quays, wharfs, places, or officers, in the said town of Boston, or in the said bay or islands, until it shall sufficiently appear to his Majesty, that full satisfaction hath been made by or on behalf of the inhabitants of the said town of Boston, to the United Company of merchants of England, trading to the East Indies, for the damages sustained by the said Company.

Harsh consequences awaited those who broke the rules. Wharf owners who permitted unauthorized transportation of goods risked losing three times the value of the contraband. Ships found within the restricted area could be compelled to depart, and failure to comply could lead to the confiscation of both the ship and its contents.

How could the blockade be lifted, and peace restored? The King offered this ultimatum: repay the East India Trade Company for the tea dumped into the harbor.

Does this demand feel eerily contemporary?

As David Randall aptly noted, haunting echoes of 18th-century British governance still resonate today. Much like Parliament flexed its muscle to discipline Boston, modern bureaucrats wield their influence to enforce compliance with their divisive agendas.

Higher education bureaucrats frequently nudge faculty—and students—towards conforming to leftist orthodoxy. One former professor, for example, was escorted off campus by police and cast out from academia’s inner circles seemingly for seeking to dispel myths about police brutality—black individuals are not disproportionately killed, beaten, nor arrested by police. One could guess that if he had supported the idea that police frequently target black individuals solely based on race, he might still hold his position—he might have even been promoted to dean.

The tendency for people to impose tyranny on others, however, is like a contagion; the thirst for power spreads beyond Ivy Towers and into the corner offices of state and federal buildings.

As Randall reminds us, government bureaucrats wielded their power in the strangest ways during the COVID-19 pandemic. Christians, for example, were denied the right to worship while strip clubs remained open during lockdowns.

And now, the most draconian decree: use the correct pronouns and titles of a person confused about their gender or prepare to dance around the law’s periphery.

For Americans in 1774, these demands might have been the final straw—a paper straw in some areas.

As news of the Boston Port Act reached the American colonies on May 11, 1774, immediate outrage ignited. According to Jared Peatman, now Senior Fellow at the George Washington University Center for Excellence in Public Leadership, the May 16 edition of the Boston Evening Post focused extensively on the impending crisis, publishing the text of the Act and expressing the town’s indignation.

A writer calling himself ‘JUSTICE’ wrote, ‘Without the shadow of evidence, without any direct accusation against the town, with all the circumstances of suspicion that their enemies were the authors of this outrage, the town of Boston is to be punished with a severity of which the worst times of this country cannot furnish a single example.’

Bostonians quickly called for a unified colonial response. An editorial in the May 16 Boston Evening Post titled “AMERICANS” urged all colonies to unite against British tyranny, warning that failure to do so would result in collective enslavement.

According to Peatman, the same edition reported that Paul Revere dispatched to New York and Philadelphia to rally support for a unified opposition. Bostonians also advocated for a collective boycott of British imports and exports, hoping to share their economic suffering with other colonies and mount a stronger resistance against British policies.

Such forms of resistance are with us today.

During the pandemic, certain states boldly defied federal control over public universities and K-12 schools. Journalists document the federal government’s border crisis. Texas is shouldering the responsibility of protecting the southern border. And, contributors to this site unveil the corruption within our once-revered academic institutions.

Though the attire has shifted from red coats to navy blue suits, the tyrants’ familiar tactics of ‘rules for thee but not for me’ persist. Yet, in parallel, so does the enduring rebellious spirit that defines America.

Art by Beck & Stone

There are several other things about the Boston Port Act often missed — and may well not have been considered by those who wrote it.

First, we need to understand that shipping back then was vastly different than today, 18th Century ships were tiny and had fairly shallow drafts which meant that in calm weather they could come in fairly close to a beach at high tide and unload cargo to rowboats or even just toss it overboard and come back for it at low tide when the water level would be 11-13 feet lower

I’ve personally seen the latter done with 100 lb propane “bottles” which weigh about 160 lbs full — the salt water’s not so great for the brass valves but this is what people did when they had to bring them out on lobster boats. Likewise, I’ve seen telephone poles towed out by lobster boat and then left on the beach until low tide when the pole truck could back down and get them.

Revere Beach — three miles long and five miles north of Boston would have been ideal for this, as were all of the since-filled-in tidal mudflats. Some of the Patriots, notably John Hancock, were notorious smugglers and the other thing the Port Act did is essentially declare already-smuggled goods in warehouses as contraband as “where/how did you get it?”

Second, much as we nonchalantly hop onto an Interstate highway for an exit or two, people of this era used the ocean for local transportation of goods. The roads of the era were *so* bad that it was easier to sail firewood 300 miles down from Maine than to cart it 30 miles over the rutted roads of the era. The Port Act would have applied to the transshipment of goods as well.

Third, while it exempted the import of food & fuel (i.e. grain and firewood), this was an era of barter when most folk didn’t have hard currency. (Something that also led to Shay’s Rebellion.) The British government did, as did those associated with it, and they could thus pay hard currency for their firewood and grain.

Fourth, in the days of sail, it wasn’t always possible to leave in six hours — even today, it is not always wise to do so. Tide wasn’t as much an issue as it was in New York, but wind definitely was.

My point is that you need to think of the Port Act in terms of the 18th Century and not today.

May 30th will live in infany,

Yes, it will. Game over. The United States is a tyranny now.