As angry crowds of student protesters gathered at elite universities across the nation to call for a ceasefire—and, in many cases, to echo the Hamas demands for the destruction of Israel—many are no doubt inspired by the vision of earlier student protesters who brought an end to the senseless violence that resulted from American intervention in Vietnam six decades ago. Indeed, it can be argued that the entire process of turning American universities into centers of wokeness and intolerance was started by Vietnam protesters.

I witnessed those confrontations up close over the better part of a decade, debated many of their leaders, and later co-taught an interdisciplinary postgraduate seminar on the Vietnam War for three decades at the University of Virginia before my 2020 retirement. It occurred to me that sharing some realities with today’s student protesters might be helpful.

The 1960s protesters were not a homogeneous group but rather a gathering of individuals motivated by varying considerations. Some factions were larger than others, but I divided them at the time into four basic categories:

- A good number could not have found Vietnam on an outline map of the world and had little interest in being able to do so. To them, joining large protests was the 1960s equivalent of the “panty raids” that amused their predecessors a decade or so earlier. It was an opportunity to assemble in large groups, make some noise, “courageously” challenge authority, and make memories for the future—more than one protester admitted to me that their primary draw was that “anti-war chicks” were “easy” and they hoped, as they so eloquently put it, to “get laid” after the rally.

- Another group seemed primarily motivated by self-preservation and securing their own personal comfort. They neither knew nor cared why Americans were fighting and dying in Vietnam, but they had no interest in possibly being drafted—or having their boyfriends drafted—or even being pressured to fulfill some “patriotic duty” by volunteering for military service. I have no idea what percentage of the crowds were composed of individuals in this category, but after the draft ended, the anti-war movement was never again able to assemble vast crowds.

- A much smaller group was composed of hard-core ideologues, ranging from actual Communist Party (CPUSA) members to individuals who had developed a profound disdain for the United States because of such manifest flaws as its long history of slavery, racial segregation, and the like. These protesters viewed whatever was going on in Vietnam as part of a larger moral struggle for justice. They also included a good number of socially inept hangers-on who seemed only able to find friends by embracing radical causes.

- And finally, what seemed to be by far the largest category were well-meaning students who recognized that peace was preferable to war and felt the war was endangering countless lives for no clear purpose. Some of this group conceded that communism was undesirable. Still, they were outraged after being told that the United States had intervened to restore French colonial rule and had actually blocked the free elections agreed to in the 1954 Geneva Accords—elections even President Eisenhower acknowledged would have led to an 80 percent victory by the popular “Nationalist” Ho Chi Minh. Contrary to State Department claims that America was responding to “Aggression from the North”—the title of a 1965 white paper—these protesters believed the revolution began in the South under the leadership of the independent “National Liberation Front.”

In reality, the critics were factually wrong on virtually every issue. After the war, Hanoi published its official history that thoroughly documented a 1959 Politburo decision to open the Ho Chi Minh Trail and start sending troops, weapons, and supplies through Laos and Cambodia to promote the overthrow of the government of the Republic of [South] Vietnam by armed force. That was every bit as much a violation of the UN Charter as when temporarily divided North Korea invaded South Korea in June of 1950, which was denounced at the time as illegal aggression by the UN Security Council.

Space does not permit a detailed refutation of all of their arguments here, but in 1972, I used the newly-released “Pentagon Papers” to demonstrate that most of their other arguments against the war were equally fallacious— a more recent presentation on YouTube can be found here starting at 14 min. Put simply, America’s enemies ran a brilliant political warfare campaign that deceived a lot of American students into doing things they honestly felt were honorable but actually led to horrendous consequences.

To give just one example, around 1968, at Earlham College in Indiana, I debated Carl Oglesby, who had served as President of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) from 1965 to 1966. I used my affirmative presentation to refute every single argument he had just made rather than saving that for rebuttal.

I began by displaying an official Party history published by Hanoi in English that acknowledged Ho’s role as a cofounder of the French Communist Party in 1920, followed by his training in Moscow and decades of work around the world for the Communist International (COMINTERN).

In response to Oglesby’s claim that even President Eisenhower had admitted Ho Chi Minh would have won a free election in 1956, I first noted that the United States and South Vietnam had refused to sign anything at Geneva and had expressly rejected the Communist proposal for unsupervised reunification elections—demanding instead that such elections “be supervised by the United Nations to insure they are conducted fairly.” Then, I produced a copy of Ike’s Mandate for Change and read the full sentence Oglesby had partly quoted, which referred to a possible earlier election between Ho and the unpopular French puppet Bao Dai.

I had earlier written to President Eisenhower, noting that war critics were using this quotation. I produced a copy of the letter I had received back confirming that he was being misquoted. I slid both documents down the table—along with various other bits of “evidence” I had presented during my remarks as I decimated his assertions—so Mr. Oglesby could examine them and perhaps challenge them during rebuttal.

Oglesby had claimed our Vietnamese opponents “did not care” about the U.S.-Soviet Cold War rivalry, so in response, I produced an article from the May 1966 issue of Hoc Tap, “Studies,” the theoretical journal of the Vietnamese Communist Party, which declared: “In the sphere of international affairs, we [North Vietnam] are a member of the Socialist Camp headed by the great Soviet Union and aligned against the Imperialist Camp headed by the United States.” I slid that document, too, down the table to the visibly dismayed Oglesby.

When it came time for a rebuttal, the former SDS leader walked up to the microphone, declared, “I have nothing further to say,” and sat down. The debate was over. And it was hardly unique among my many debates during the conflict—although a far more common response was simply not showing up.

On the 50th anniversary of the enactment of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution—by which Congress, by a margin of 99.6 percent, had formally authorized the president to use armed force to protect victims of Communist aggression in Indochina (including Cambodia)—the Vietnam Veterans for Factual History (VVFH) approached more than two-dozen prominent leaders from the 1960s anti-war movement to find someone to take part in a National Press Club debate on the arguments they had made at the time. No one was willing to defend those positions, so the American people never got to hear that debate. The invitation remains open.

In today’s politically correct environment, where facts inconsistent with woke orthodoxy are routinely suppressed and speakers offering viewpoint diversity often are canceled, few students are even aware of these realities. Most are taught in high school and college that Vietnam was an “unnecessary, unwinnable, unlawful,” and obviously foolish blunder—and that the anti-war protesters were the real “heroes” of the era. But they have been misinformed.

In truth, student protesters of the 1960s got virtually everything wrong and bore moral responsibility for the slaughter of millions and the loss of any chance at freedom for tens of millions more. Their actions led directly to congressional Liberals dramatically reducing aid to South Vietnam and outlawing the use of appropriated funds for combat operations by U.S. armed forces anywhere in Indochina seeking to defend victims of Communist aggression—betraying a solemn pledge America had made in 1955 by ratifying the SEATO Treaty with the consent of nearly 100 percent of the Senate. In a very real sense, under pressure from a misguided American “peace movement” whose anger was only exceeded by its ignorance, Congress “snatched defeat from the jaws of victory” at a time when South Vietnam and its allies were clearly winning on the battlefields of Vietnam.

Two common themes of the anti-Vietnam protesters were that ending the war would “stop the killing” and “promote human rights.” But more people died during the first four years following the 1975 “Liberation” of South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos than had died in combat during the previous 14 years of war.

The Yale University Cambodia Genocide Program concluded that roughly 1.7 million Cambodians—more than 20 percent of the country’s entire population—perished under the brutal Pol Pot regime. More than 500,000 people died or vanished while trying to flee South Vietnam as “Boat People” following “Liberation,” and large numbers of other South Vietnamese were executed from “blood-debt” lists or died in “Reeducation Camps” and “New Economic Zones.”

The reality of “human rights” in the unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam following the Communist victory was captured in the 1978 Freedom House annual survey of Freedom in the World, which proclaimed: “Vietnam is as free as Korea (North), less free than China (Mainland).”

Few, if any, anti-Vietnam protesters in the 1960s believed they were fighting for these oppressive results—which included in Cambodia the world’s worst genocide of the 20th century on a per annum, per capita basis. Their motives were often pure, and their convictions presumably sincere. But the consequences of their actions nevertheless were horrific.

I have not even addressed the indirect consequences of abandoning Indochina, including well over 1 million deaths when the Soviet Union sent nearly 50,000 Cuban troops into Angola and unleashed revolutions in Central America before invading Afghanistan. Emboldened by America’s withdrawal from the global stage, Iran used a paramilitary group—later known as Hezbollah—to murder 241 sleeping Marines in Beirut and formed similar proxy groups to murder Jews and try to destroy Israel. Osama bin Laden told an American journalist in 1998 that America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, Beirut, and Somalia showed we could “not accept casualties”—which almost certainly was a key factor in his decision to launch the 9/11 attacks that ultimately led to the loss of another estimated 4 to 5 million lives in the decades that followed.

They may not realize it, but today’s college protesters are encouraging Iran and its proxies in their efforts to murder Jews and destroy Israel, and are signaling tyrants in Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang, and elsewhere that America is “short of breath” and this may be a safe time for further aggression. The risks from such miscalculations include a nuclear World War III.

I do not question the constitutional rights of Americans to oppose assistance or investments in Israel peacefully, but I would respectfully suggest to them that the stakes involved are far more serious than they may perceive, and if history ultimately shows they were misled, they will bear moral responsibility for the consequences of their actions. My message is not that students should never protest, but when the consequences include the possible loss of human lives and freedom, they should be careful to get their facts right before doing so. And, if their goal is to emulate the anti-war protests of the Vietnam War era, they might want to first examine the actual human costs of those misguided efforts.

In the interests of fairness and promoting a free exchange of ideas, if current or former anti-war protesters believe my comments to be unfair, I will be delighted to engage in public debates with one or more champions of their choice.

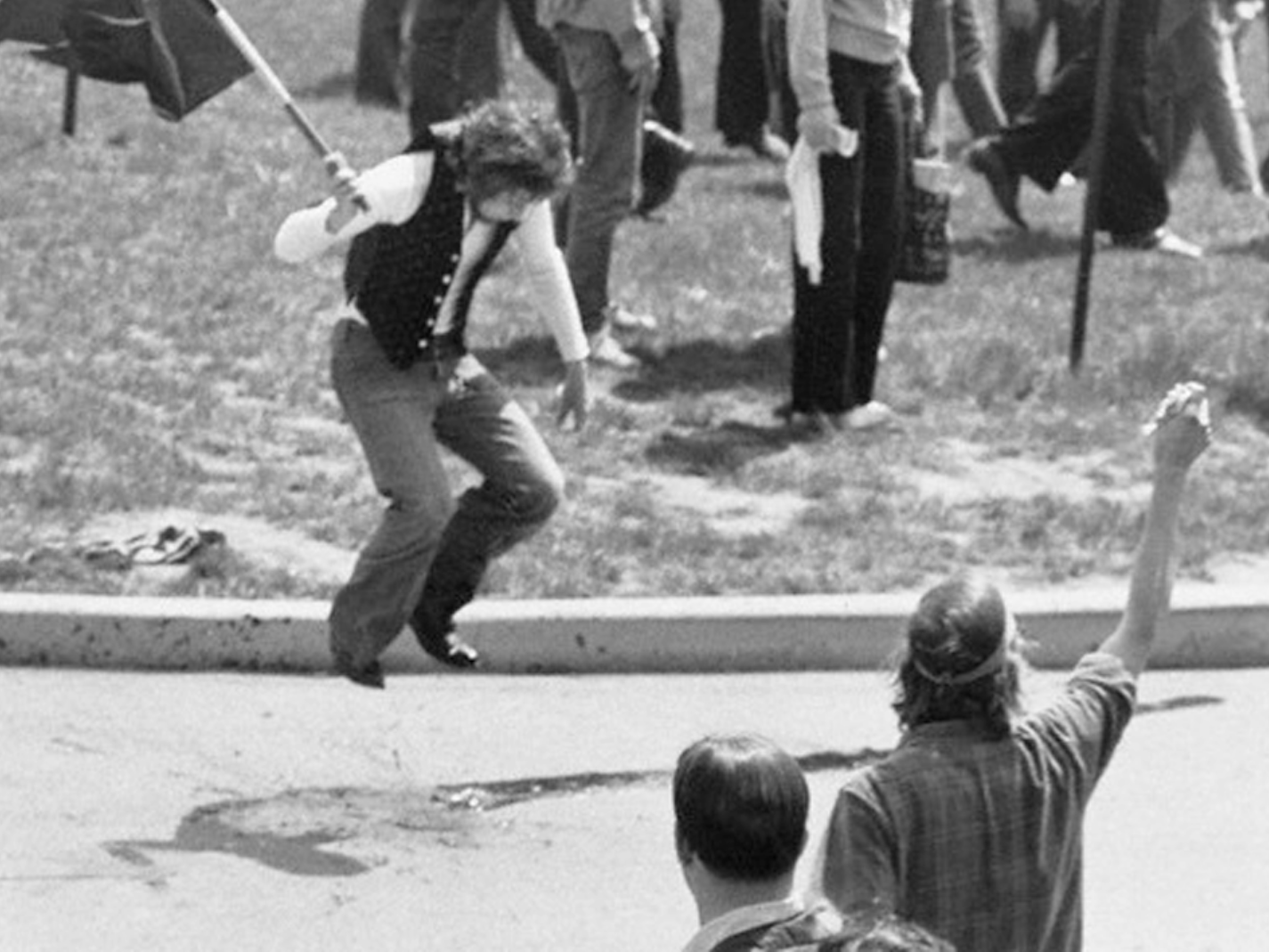

Photo by TommyJapan1 — Flickr

This needs to be shared as widely as possible. While I would like to sing the article and author’s praises, the response would be larger than the article itself and a lot less readable! A magnificent tour de force on multiple counts, not least of them the truth!

It’s a question of WHAT river and WHICH sea — and can any of these idiots find either on a map?