Once again, the Washington Post misses the mark when it associates “zombie” CVS of Washington, D.C., or America’s shoplifting pandemic with the decline of liberal democracy.

Ironically, torchbearers of modern-day progressivism are willfully oblivious to the fact that their illiberal ideology, not liberal democracy itself, is at the root of many societal problems, including urban decay and the lawlessness we face today.

In fact, true liberal scholars from the 20th century, who were daring, progressive thinkers of their times, were never so quick to dismiss the American experiment of self-government and free market competition. Unlike their 21st-century successors who call themselves “liberals” yet behave quite illiberally, these great thinkers devoted entire academic careers to the study of Western capitalism and the preservation of the fragile liberal democracy ideal. They may disagree on the epistemology or specific ways to achieve intended goals, but ultimately these intellectual giants could not agree more on the fundamental issue: the Western liberal democratic ideal is worth fighting for.

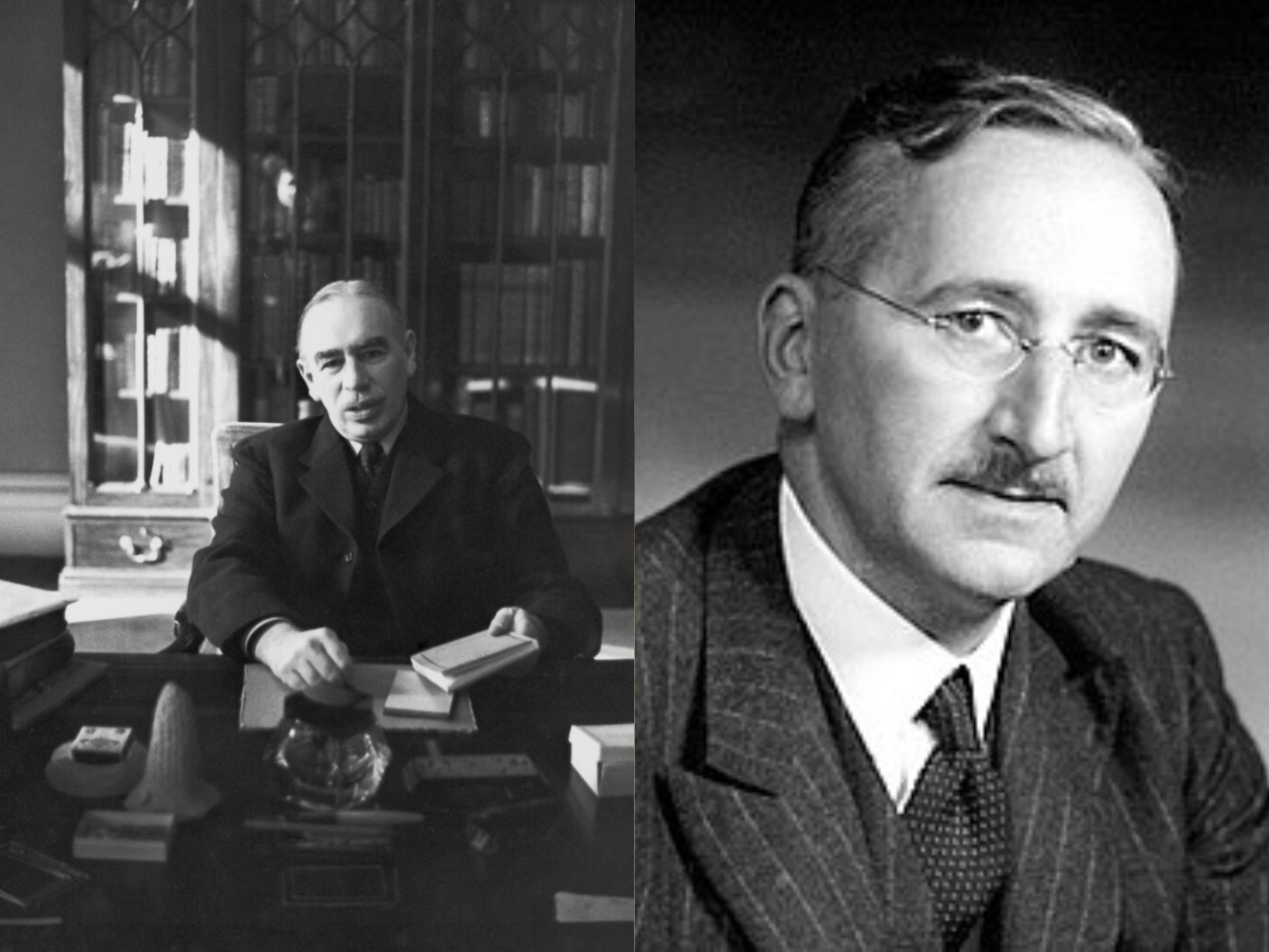

John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich August Hayek, two influential economists, provide a perfect example.

Although Keynes and Hayek represented two competing paradigms of economic thought, with Keynesianism promoting the aggregate-demand theory of employment and government interventions and Hayek’s works defending classical liberalism, both were unambiguously committed to safeguarding liberal democracy from illiberal alternatives. Their normative motivation was similar: to Keynes, it was to save capitalism from its booms and busts, and to Hayek, it was to save the Western world from authoritarianism.

Keynes’ career was renowned for his foresight and a proclivity for choosing the lesser of two evils. After World War I, he opposed the Versailles Treaty. In his book, The Economic Consequences of Peace (1919), Keynes argued that large-scale reparations would harm Germany. He knew that the treaty would spawn greater discord. During the Great Depression of 1929 to 1933, Keynes witnessed the downfall largely caused by extreme externalities of market fundamentalism and a supply-side economy.

This pragmatic mindset later prompted him to write, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), a cornerstone of managed capitalism, or Keynesianism. This book, along with an earlier book, The End of Laissez-Faire (1926), facilitated an economic thought revolution that proposed a demand-side theory of employment and promoted government interventions to maximize aggregate demand and countercyclical employment during economic stress.

Keynes’ demand-side economic policy with a role for government—fiscal policy—and central bank—monetary policy—was widely adopted in the late 1930s.

Keynes wanted to theorize a more stable and sustainable form of capitalism that was not subject to drastic and unexpected boom-and-bust cycles. A more managed form of capitalism is desired in order to deter individuals and institutions from seeking radical political alternatives like Communism. Since the unfettered market afflicted all major capitalist economies of the post-war era, it was the duty of governments to step in and create full employment. Full employment can help generate a content population and would ultimately discourage alternative movements.

In The End of Laissez-Faire, Keynes wrote:

Many people, who are really objecting to capitalism as a way of life, argue as though they were objecting to it on the grounds of its inefficiency in attaining its own goals…Nevertheless, a time may be coming when we shall get clearer than at present as to when we are talking about capitalism as an efficient or inefficient technique, and when we are talking about it as desirable or objectionable in itself. For my part I think capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable. Our problem is to work out a social organization which shall be as efficient as possible without offending our notions of a satisfactory way of life.

He reiterated the ontological position for liberal democracy in The General Theory:

The purpose of the book as a whole may be described as the establishment of an anti-Marxian socialism, a reaction against laissez-faire built on theoretical foundations totally unlike those of Marx in being based on a repudiation instead of on an acceptance of the classical hypotheses, and on an unfettering of competition instead of its abolition.

When Keynesian economics of aggregate demand and government intervention became the new economic paradigm in the 1940s, Hayek’s research in defense of classical liberalism was carried on in a parallel fashion. His book, The Road to Serfdom (1944), was well received throughout academia then and still remains very popular among students of political economy. As someone who had spent half of his adult life in his native Austria and the other half in the U.S. and England, Hayek came from an emotional place to prevent the human tragedies of Nazi Germany from taking roots in his adopted homeland of America:

Few are ready to recognise that the rise of Fascism and Nazism was not a reaction against the socialist trends of the preceding period, but a necessary outcome of those tendencies. This is a truth which most people were unwilling to see even when the similarities of many of the repellent features of the internal regimes in communist Russia and national-socialist Germany were widely recognised. As a result, many who think themselves infinitely superior to the aberrations of Nazism and sincerely hate all its manifestations, work at the same time for ideals whose realisation would lead straight to the abhorred tyranny.

This famous quote establishes Hayek’s normative frame, that both Fascism and Nazism were not born as a response to socialism, but because of a fundamental authoritarian impulse predicated on the need to control. Those who purport any form of centralized planning would inevitably undercut man’s natural right to self-govern. The potential for tyranny is too great, while the tendencies and temptations moving a democratic government towards authoritarianism are ever so present.

To Hayek, centralized planning is fundamentally discordant with a free and democratic society. Too much power would be placed in the hands of too few:

Have not the parties of the Left and those of the Right been deceived by believing that the National Socialist Party was in the service of the capitalists and opposed to all forms of socialism? How many features of Hitler’s system have not been recommended to us for imitation from the most unexpected quarters, unaware that they are an integral part of that system and incompatible with the free society we hope to preserve? The number of dangerous mistakes we have made before and since the outbreak of war because we do not understand the opponent with whom we are faced is appalling. It seems almost as if we did not want to understand the development that has produced totalitarianism because such an understanding might destroy some of the dearest illusions to which we are determined to cling.

When Keynesian economics waxed and waned, Hayek continued to expand his liberalist program of constructing a free society through the invisible hand. In 1945, Hayek wrote “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” in which he presented a case against centralized price controls because “it (the price system) fulfills less perfectly as prices grow more rigid.”

In 1976, Hayek wrote The Denationalization of Money, advocating for a free market in money as a solution to stop inflation and suggesting that “government should be deprived of its monopoly of the issue of money.” Subsequently, The Denationalization of Money became the centerpiece of the Austrian free banking school of the 20th century, which emerged to limit the power of central banks and enlarge that of private commercial banks.

As a productive economist, Hayek undertook various projects during his lifetime. All his works seemed to carry some sort of paradigmatic coherence in that the research was always based on a firm position on classical liberalism and an academically minded opposition to Keynesianism. To the Austrian-American scholar, any attempt to pursue the Keynesian way would essentially lead to the dissolution of the society that many seek to avoid through government intervention.

But all roads lead to Rome.

Albeit divergent in epistemological and methodological substance, the Keynesian paradigm of managed capitalism and Hayek’s paradigm of classical economic liberalism share a common higher goal: to safeguard liberal democracy. Struck by the miseries of the Great Depression and concerns over the advent of communism, Keynes hypothesized that proper government intervention was necessary to save capitalism from self-destruction. Opposed to a centralized economy and troubled by its authoritarian tendencies, Hayek insisted that a free economy be essential to a free society.

Photo of Keynes (left) — Patrick Chartrain — Flickr & Photo of Hayek (right) — Mises Institute — Wikipedia & Edited by Jared Gould

Very well said.

I would only add that Hayek also made the crucial point that where government has authoritarian power “to do good” it will attract the worst kinds of people. It attracts schemers who will use that power to enrich themselves and visionaries who think they know how to run the nation. Those people disdain the rule of law because it inhibits them from doing what they want.

The trouble with authority is that it can’t be contained.

On one hand, Keynes believed in the power of government intervention and deficit spending to stimulate economic growth and avoid prolonged periods of recession. He argued that savings should be put to productive use through investment rather than just being hoarded, and that a strong social safety net was crucial in maintaining a stable and prosperous society.