We’ve been exploring the pros and cons of the College Cost Reduction Act, a bill introduced by House Republicans. Here we continue that effort, asking which types of colleges would gain or lose under the bill.

Two new features the bill introduces are bonus payments and risk sharing penalties that colleges would receive to pay based on their earnings-price ratio (EPR), which is the median earnings of graduates after graduating—minus a multiple of the poverty line—divided by the price paid for the degree. For example, if a graduate earned $55,000 and the relevant poverty line is $25,000, the calculation’s earnings would be $30,000. If the student paid $15,000 throughout their education, the EPR would be two. If they paid $60,000, the EPR would be 0.5, and if they paid $120,000, the EPR would be 0.25.

For students, a higher EPR is better since it indicates the benefits they received from the education—in the form of higher earnings—are high relative to the cost. One of the great things about the College Cost Reduction Act is that it begins to align the college’s incentives with what’s good for students. It does so by using the EPR to determine the college’s performance bonus and its risk-sharing payments—colleges with a higher EPR get rewarded, while those with a low EPR are sanctioned.

How does it work?

The performance bonus—called Promise grants—are equal to the total Pell funding for a college times EPR—one times the college’s completion rate. Suppose a college whose students receive 1 million in Pell grants had a completion rate of 80 percent: if their EPR is two, then the college would get a $800,000 performance bonus; if their EPR is 1.5, they would get a $400,000 bonus. Colleges with an EPR less than one would not receive any performance bonus.

The sanctions take the form of risk-sharing payments, which hold colleges responsible for some of the student loan payments their former students fail to make. Colleges with a lower EPR repay more than colleges with a higher EPR. The college’s share is equal to one EPR. If a college’s former students missed $1 million of student loan repayments, if the college has an EPR of 0.25, the college would be required to pay 75 percent of that ($750,000). If the college’s EPR is 1.25, the college would not be required to pay anything.

To recap, the EPR aligns colleges’ incentives to students’ best interests. Things that benefit students, like higher post-graduation earnings or lower college costs, would also benefit colleges via higher performance bonuses and lower risk-sharing payments.

Because earnings and costs vary across types of colleges, the net effect on funding—the performance bonus minus the risk sharing payments—varies. Preston Cooper has done a lot of work analyzing the impact on individual colleges. His calculations reveal some surprising results, as shown in the figures below.

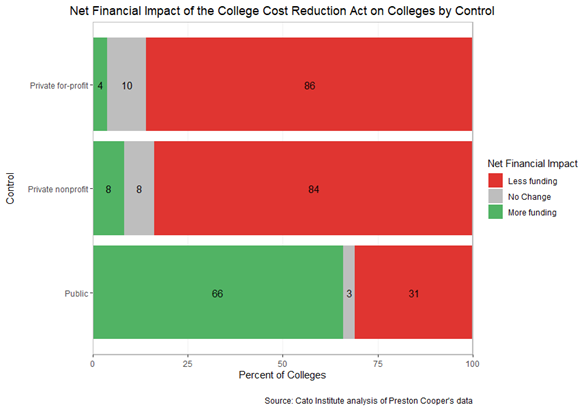

To begin, the bill would benefit public colleges while sanctioning private colleges. Two-thirds of public colleges would receive higher funding, whereas only eight percent of private nonprofit colleges and four percent of private for-profit colleges would. Only 31 percent of public colleges would receive less funding, while 84 percent of private nonprofit and 86 percent of private for-profit colleges would.

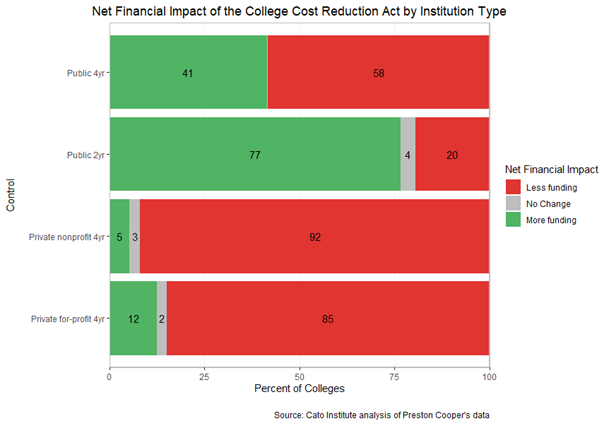

As shown in the figure below, community colleges in particular are heavily rewarded. Over three quarters of community colleges would receive more funding under the bill. In contrast, 41 percent of public four-year colleges, five percent of private nonprofit four-year colleges, and 12 percent of private for-profit four-year colleges would receive more funding.

But while community colleges are the big winners, the community college’s advocacy arm, the American Association of Community Colleges, opposes the bill:

Although preliminary analyses indicate that community colleges would fare better than other sectors under the proposal, we have consistently opposed risk-sharing, because of its basic premise that institutions should be held responsible for student loan repayments.

Needless to say, this is a bit surprising. Community colleges have been complaining about underfunding for years; so, it’s odd they oppose an idea to transfer money from four-year colleges to community colleges. But even taking their argument at face value, that they oppose risk sharing on principle, just shows how out of touch higher education is.

The days when the public just gave money to colleges with virtually no accountability mechanisms are numbered. There is bipartisan agreement that more accountability is needed in higher education, and risk-sharing in particular is gaining traction. While the College Cost Reduction Act is a bill from Republicans, the Center for American Progress complied risk-sharing proposals a few years ago. Organizations on the left pushing for some type of risk-sharing include The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS), the Urban Institute, and the Center for American Progress.

With so much agreement across the ideological spectrum, risk sharing is coming to higher education, and it’ll be a good day when it does.

Photo by mnirat — Adobe Stock — Asset ID#: 425568683

The real question is how does one define earnings? If we don’t address that now, we are going to have a lot of unintended consequences because it isn’t just Mike & Mary going to work for MegaCorp after graduation — that’s simple.

Eddie the Electrician and Danny the Diesel Mechanic attend Ye Olde Community College and get an excellent education in their fields — both will be millionaires in their 40s because they are responsible businessmen who invest back into the business. So do you look at their gross income or their net income? And how do you define net income?

Frank the Farmer may have a gross income of $100K but when you deduct fertilizer, fuel, equipment rental, and rental of a hay field, he may only net $10K. He’s building his herd, he’ll be doing better later, but he’s just starting out.

Molly went to college for the Mrs. Degree and latched onto a lawyer a dozen years older than she, and they have a $300K income. On the one hand, Mt. Holyoke did give her the opportunities to meet rich men, on the other, is that what a college education should be for?

And then what about the babies? We *do* need babies, and we definitely need educated families having them as all parents homeschool to some extent. Hence we could wind up with a situation that we don’t want:

College A is traditional, religious, and about a third of the female students get married upon graduation, have a couple of children, and then enter the workforce in their 30s.

College B is lesbian central, where “breeders” are despised and absolutely no one gets married upon graduation — and any pregnancy would inevitably end in abortion.

College A would be penalized and College B rewarded — and we need to somehow get around that. We are shooting ourselves in the foot if we penalize motherhood.