The recently released College Cost Reduction Act (CCRA) improves the financial aid system.

The determination of a student’s financial aid eligibility involves two key components: the Student Aid Index (SAI) and the Cost of Attendance (CoA). The SAI represents the government’s estimate of what a student—and their parents if the student is dependent—can afford to contribute to college expenses. Formerly known as the Expected Family Contribution (EFC), the SAI is a crucial factor in the aid calculation. The CoA encompasses the comprehensive cost of attending college, covering tuition, fees, room, board, books, transportation, and other expenses. The aid eligibility is then determined by subtracting the SAI from the CoA. It’s important to note that specific financial aid programs have set maximum amounts, influencing a student’s final aid package. For instance, a student might be eligible for a Pell Grant of $7,000, $3,000 in work-study, and $5,000 in loans. This formula provides a framework for assessing the financial support a student can access, considering both their financial capacity and the overall cost of their chosen educational institution.

The median cost of college (MCoC) would replace the CoA used to determine aid eligibility with the same value for all students within a credential and academic field. For example, suppose three colleges are offering a bachelor’s degree in data science and that the CoA for that program at college A is $15,000, $20,000 at college B, and $25,000 at college C. Under the current system, students at College C would be eligible for much more aid than students at College A. However, under the MCoC, all students would have their aid eligibility determined by the median among the colleges, which in this case would be $20,000.

A few years ago, I wrote a paper that laid out the case for replacing CoA with MCoC, which covered many of the benefits, but here I’ll highlight three of the most important.

MCoC would help contain college costs through a decentralized and market-driven process.

MCoC would increase the amount of aid students attending low-cost colleges are eligible for while reducing the amount of aid students at high-cost colleges are eligible for. This will put pressure on high-cost colleges to reduce or at least slow the growth in their spending.

Given the high cost of college, encouraging spending restraint is certainly desirable, and the MCoC does so through a decentralized and market-driven process rather than through a top-down and politicized process that other methods like price controls entail.

MCoC would improve the financial aid process.

Since aid eligibility depends on both SAI and CoA, the government has a student fill out the FAFSA and send that information to the colleges, which then plug in their CoA and send students award letters detailing how much aid they can receive.

From the students’ perspective, this is troubling. First, the college receives comprehensive data on their family’s income and assets, which the colleges can then use for their own benefit. Many colleges will price discriminate, and some likely will flag rich families for their fundraising drives. Second, the student doesn’t receive any information about how much aid they are eligible for until months after filling out the FAFSA.

MCoC addresses both problems. With the MCoC, there would be no need to send students’ FAFSA information to the colleges, which will help protect student and parent privacy, and students would be able to receive their aid eligibility immediately after submitting the FAFSA.

MCoC would lead to lower tuition.

One of the biggest problems with CoA is that it encourages colleges to raise tuition. When an increase in tuition leads to an increase in aid eligibility, colleges are much more likely to raise tuition—this is referred to as the Bennett Hypothesis—since their students are—at least partially—shielded from the higher cost by the increase in aid. Unfortunately, CoA provides a direct link between high prices and high aid—when a college raises its tuition by $1, its students are eligible for $1 more in aid.

The MCoC fights against the Bennett Hypothesis by severing the link between a tuition increase and an increase in aid. Colleges could still raise tuition, but their students won’t get more aid—see footnote 8 for the rare exceptions to this—which will help constrain tuition.

While MCoC will tend to restrain tuition in general by neutralizing the Bennett Hypothesis, it will also likely lead to lower tuition at some high-cost colleges while not leading to higher tuition at low-cost colleges. As I noted in the formerly mentioned study:

the price effects are likely to be asymmetric—high-cost programs could be incentivized to lower their tuition and fees, but it is less likely that low-cost programs will be incentivized to raise their tuition and fees. The reason for the asymmetry is that the median cost of college adds a constraint for high-cost programs—they can no longer count on higher aid eligibility for their students. In contrast, low-cost programs face no new constraints or options. For low-cost programs, under both the current system and the median cost of college method, they could raise tuition and have some of the consequences partially offset by aid. So while their students may actually be eligible for higher aid amounts under the median cost of college, other factors that drove these programs to keep their tuition relatively low would still be in effect, so it is unlikely these programs would respond to the new system by raising tuition.

But what about the objections to replacing CoA with MCoC? There are two common ones that I’ve seen in response to my paper.

High-cost colleges object to the MCoC.

It is true that half of college programs in each field with a CoA above the MCoC would see their students eligible for less aid under MCoC than CoA. But this is a feature, not a bug.

It’s reasonable for the government to provide higher subsidies for higher-quality programs, but the current system uses price as a proxy for quality, simply assuming that higher-cost colleges are better and awarding their students more aid. However, the assumption that a higher price implies higher quality is deeply flawed. Until credible differences in quality among programs are established, there is no justification for the government to provide some college programs with higher subsidies than others.

My response to the high-cost programs that object to MCoC: “You say you are of higher quality. Prove it.” I’m open to providing high-quality programs with higher subsidies; I don’t accept the assumption that high price equals high quality.

Geographic differences in the cost of living.

Another common objection to the MCoC is that some areas of the country are more expensive to live in, which means that an MCoC would tend to reduce the aid available to students in those areas. It is certainly true that some places are more expensive to live in than others, yet I remain unswayed that this justifies using different cost of living figures for different cities.

To begin with, just because an area is more expensive to live in is not a convincing rationale for additional subsidies. In contrast, high costs generally indicate that the activity should be relocated. As I noted in “The Case for Replacing Cost of Attendance With Median Cost of College:”

The higher cost of growing oranges in Alaska than in Florida is not a convincing argument that we should increase subsidies for orange-growing in Alaska.

Higher costs that are accompanied by higher benefits could still be worth incurring, but there is little reason to incur higher costs just for the sake of incurring higher costs.

Moreover, the differences in the cost of living for college students are not as large as you would expect, given the differences in the cost of living for other adults. Even more notably, the differences are inconsistent enough to justify special carveouts.

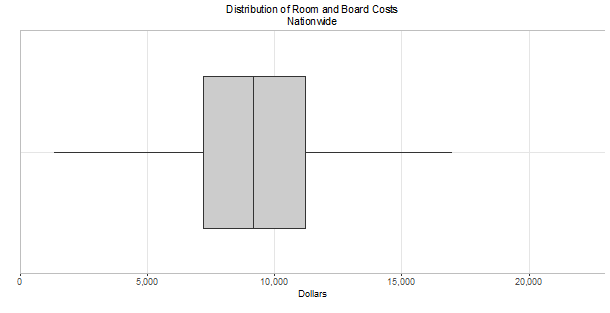

To see both points, consider the figures below, which show the distribution of off-campus room and board costs among colleges (I used data for a pre-Covid year since the post-Covid year data isn’t available yet and the Covid years may have been abnormal). For boxplots, the left-most edge of the grey box indicates the 25th percentile, the vertical bar within the grey box is the median, and the right-most edge the 75th percentile, so for the nationwide boxplot, around 25 percent of colleges have a cost for room and board of under $7,200, 50 percent under $9,180, and 75 percent under $11,230.

Created by Author

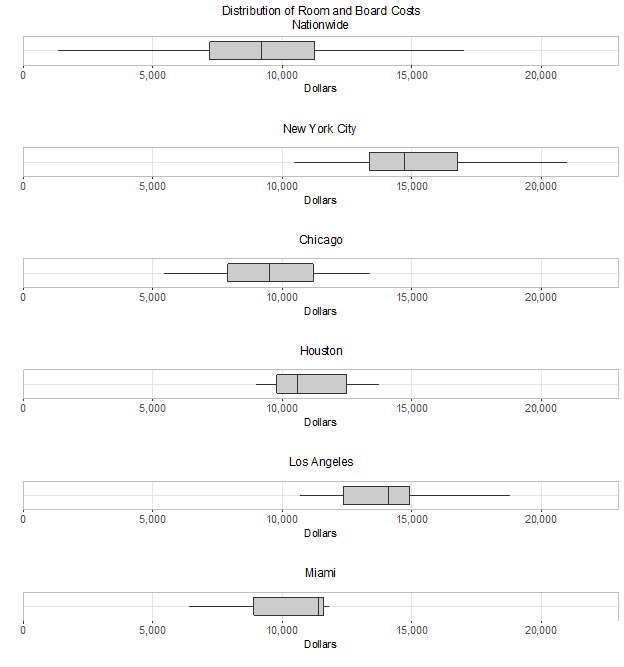

Popular indices report that the cost of living in cities like New York can be more than double the national average, so one might expect off-campus room and board costs among colleges in big cities to be double the national average, but that is not the case. The figure below displays the boxplot for the nation, as well as for the cities with the most colleges for several big states—New York, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, and Miami.

Created by Author

The cost of off-campus room and board in Chicago, Houston, and Miami are well within the range of the costs nationwide, even though Chicago and Miami are generally regarded as high cost-of-living cities. Houston is generally considered to have a moderate cost of living, yet off-campus housing in Houston is more expensive than in Chicago.

While New York and Los Angeles stand out as cities with noticeably higher costs, it’s worth noting that even in these urban centers, there exists a considerable range of expenses. In the case of New York, some colleges manage to maintain relatively low off-campus room and board costs, yet these costs still align with or exceed the upper limits observed elsewhere in the country.

I don’t doubt that many students would like to live in New York City. I too would like a penthouse overlooking Central Park, but there is no reason taxpayers should subsidize my desires, just as there is no justification for additional subsidies for students wanting to attend college in New York City.

In sum, replacing the Cost of Attendance with the Median Cost of College is one of the most exciting aspects of the new bill. It would improve the financial aid system while also helping to restrain college costs, slow tuition growth, and even lower tuition at some colleges.

Photo by jirsak — Adobe Stock — Asset ID#: 91644653

“For instance, a student might be eligible for a Pell Grant of $7,000, $3,000 in work-study, and $5,000 in loans.”

OK, for a total of $15,000. Keeping the math simple, School A is $10,000, School B is $15,000 and School C is $20.000.

This means that School B is paid for, and the student has an “unmet need” of $5,000 at School C. But what happens if the student does — as intended — and picks School A?

“a Pell Grant of $7,000, $3,000 in work-study, and $5,000 in loans.”

Option A: a Pell Grant of $7,000, $3,000 in work-study, and NO loans. Or no work-study and only $2,000 in loans (schools will usually switch these if asked).

Option B: a Pell Grant of $5,333, $1,333 in work-study, $3,333 in loans, and a $1 scholarship to make the math come out right — deducting $1,667 from all three.

Option C: a Pell Grant of $2,000, $3,000 in work-study, and $5,000 in loans.

As you can see, there is a $5,000 difference in the “free money” the student receives, and that very much will affect the student’s choice. With Option C the student is paying no more to attend the more expensive school so why shouldn’t he — it has a lovely lazy river rec center and a winning football team…

Likewise if we *really* want to bring the MCoC down, let’s simply give the student the extra $5,000 — students will go to the lower cost colleges in droves if they get the unspent share of the MCoC and that will quickly lower the MCoC for greater overall savings. We’re influencing the market here — which is our intent.

But back to the larger issue, the median cost of college and maintaining the same eligibility criteria will lead to awards exceeding the total costs of lower priced institutions and we need to think about how we deal with that.

The other thing we need to look at is the internal fabric of the Work Study program. For those not familiar with this, it consists of a Federal subsidy of the wages paid to the student — initially it was a flat 80% with the actual employer paying the remaining 20%. It’s now *usually* a 75% / 25% split with some interesting exceptions:

https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/fsa-handbook/2022-2023/vol6/ch2-federal-work-study-program

Yes — as much as 100% Federal money for “community service”, and 90% Federal money for students employed by private non profits. And perhaps worse is the requirement that a total of 7% of an institution’s work study money must go to the above.

I wonder what all these people are doing? They wouldn’t be advocating leftist political causes, would they?

And this is a far cry from what Work Study was intended to be — a program to subsidize the wages of students so that they could get work experience in their fields of study.

The devil of all of this is in the details — we need to ensure that the student actually sees the financial incentive of the cheaper schools *and* we need to demand that Work Study employment relate to the student’s actual major. An engineering student teaching math at a Title III or Title V school would be a good thing — but not teaching writing! And I dread to think of any undergrad teaching civics because the only thing most of them know are the politically correct causes de jour.

“First, the college receives comprehensive data on their family’s income and assets, which the colleges can then use for their own benefit.”

This includes knowing which students have the financial resources to sue them and which ones do not. This has far more consequences than people realize.