The Pilgrim’s treaty with the Wampanoag lasted fifty years. This would not have happened had the Wampanoag felt imposed on or exploited. Indeed, at that first Thanksgiving—a three-day feast-The Wampanoag numbered about ninety, while only fifty of the settlers were still alive. Had the Wampanoag decided to end the peaceable encounter, things would not have gone well for the residents of Plymouth.

The treaty did, however, have practical advantages for the Wampanoag. They had lost a substantial population in the years before the Mayflower arrived. An epidemic that probably began as a disease communicated by European fishermen had swept the coast and had hit the Wampanoag especially hard. They feared their traditional enemy, the Narragansett tribe, would wipe them out. The people in Plymouth rose to the occasion and sent out armed expeditions against the Wampanoags’ enemies.

Thanksgiving might be seen not simply as a feast of gratitude, but also as the cementing of a military alliance in perilous times.

The Wampanoag weren’t imagining things. Coastal New England was inhabited by native peoples as long as 7,500 years ago. But not the same native peoples. Whole cultures flowered and disappeared. About five thousand years ago, coastal New England belonged to a population archaeologists call the “Red Paint People,” after the red ocher they buried with their dead. The Red Paint People stand out because of their remarkable maritime skills. Without metal tools of any sort, they hunted swordfish—a dangerous quarry–in the open ocean from dugout canoes. But these folks suddenly disappeared about 3,800 years ago. There are competing explanations but the simplest is that they were overrun and either were killed off or fled.

In fact, from what we can piece together of the New England past, the area was likely never at peace. The Red Paint people were well supplied with weapons, not all of them for hunting. Jacques Cartier passed through the area in the 1530s and 40s and found Iroquoian-speaking Indians. When Samuel de Champlain touched coastal Maine in 1603, all the people were gone. Archaeologist Bruce Bourque suggests “probably because its inhabitants had been driven out by warfare.”[i]

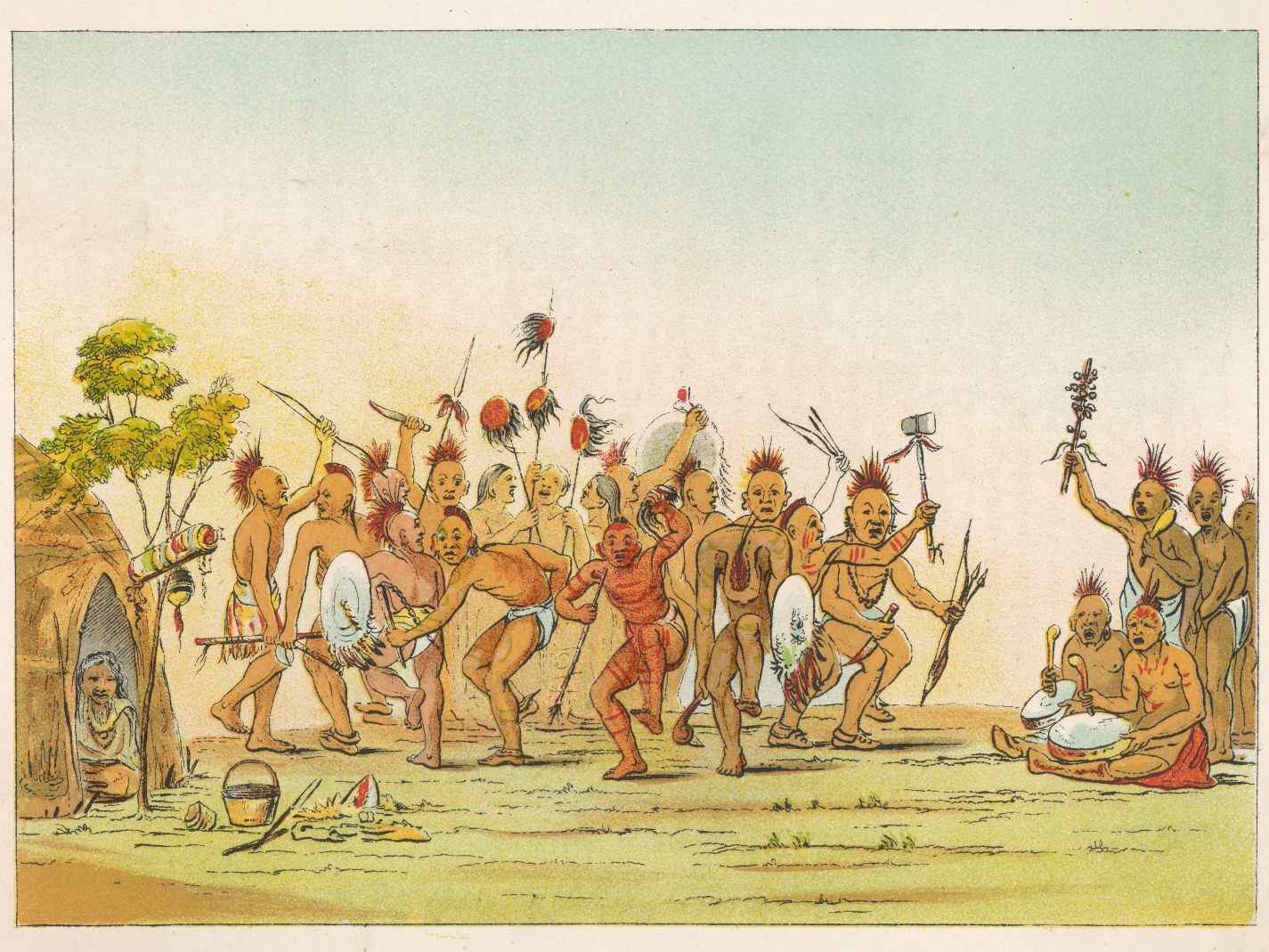

A genuine historical record began once English colonists established their beachheads on the New England coast, and those records depict endless native warfare, often directed towards the extermination of rival tribes. So, the Wampanoag in the 1620s had well-justified fears. They were survivors of a tradition of thousands of years of unending and brutal warfare. One might not think that the New England littoral was so rich in resources that it was worth the contest, but war is about more than resources. It is also about pride.

Most years, I find some occasion to comment on the Mayflower Compact and the remarkable ability of the Pilgrims and the non-Pilgrim “Strangers” who arrived with them to invent a workable form of self-government. In many ways, they set the example that would later shape American independence.

But this year, we celebrate Thanksgiving in the shadow of war. And not only war, but the kind of brutal, all-in war that the native peoples of New England knew all too well. These days, we once again hear the counter-narrative that demotes the Pilgrims as “settler colonialists” who stole land from the Indians and exploited them. The Pilgrims for sure had their hard edges, and later, English settlers responded to the attacks of Native Americans with their own kinds of ferocity.

But let us give thanks that we are at least moderately safe in this new age of barbarism. Things could be a lot worse, and they will get that way if we do not gratefully maintain the power needed to keep order in a world that is always ready to dispose of those who cannot defend themselves.

[i] I’ve drawn from Bruce Bourque. The Swordfish Hunters: The History and Ecology of an Ancient American Sea People. Piermont, New Hampshire: Bunker Hill Publishing. 2012.

Herbert M. Sylvester. Indian Wars of New England. Three Volumes. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clarke Company. 1910.

Peter W. Wood. 1620: A Critical Response to the 1619 Project. New York: Encounter Books. 2020

Oh, and the comments about Cartier and the Iroquois and Champlain? It didn’t sound right and I checked: the Iroquois Cartier saw were at what is now Quebec City, which is a stretch to call New England. And Champlain traveled up and down the Maine coast and interacted with many Abenaki or Almouchiquois. I guess fact checking isn’t part of your gig.

So the European settlers finally ended the thousands of years of unending brutal intertribal warfare and are gratefully maintaining the power needed to keep order in a new world which wants to dispose of those who cannot defend themselves?

This ignores a lot of history and research and rests on a lot of frank speculation: “There are competing explanations but the simplest is that they were overrun and either were killed off or fled.” And, Bourque’s “probably because its inhabitants had been driven out by warfare.”

The settler’s efforts in stoking the “endless native warfare, often directed towards the extermination of rival tribes” with favoritisim, manipulation, the fur trade, sometimes intentional genocide, and other times unintentional (dams), are well documented.

And where is the record of “thousands of years of unending and brutal warfare?” The idea that, “the area was likely never at peace” is absurd. Stone age peoples were undoubtedly violent and fought many wars, but there is also evidence of relatively stable societies and civilizations that lasted hundreds of years.

Isn’t it pretty to think that there were “Red Paint People” with highly developed maritime skills and an advanced culture. And how tragic that they were run off by the dirty Indians we have today, “ who live in a BIA-funded lala land,” as your pal Bruce Bourque says.

The “Red Paint People” is a noble savage trope that is largely meaningless. Google will help you discover some facts that may be inconvienient to your thesis.

So tell us, Enoch, when we guilt-ridden white Europeans do our land acknowledgements, which of the many former possessors of the land in question do we acknowledge? I did not take this article’s description of the Red Paint People as any sort of noble savage trope. I took it to mean the Red Paint People were likely human just like us — as were those they replaced and all those who replaced them. Unless you want to say we are all “noble savages,” I really don’t see your point.

“An epidemic that probably began as a disease communicated by European fishermen had swept the coast and had hit the Wampanoag especially hard.”

I know that the Europeans (particularly Columbus) are often blamed for introducing diseases which did kill upwards of 90% of the Indians, but I have two problems with that.

First, having resistance to a disease does not mean that one is contagious — in most cases, one has to actually be sick to be contagious. Knowing that you are going to be on a small boat for 10 weeks or so (the time it took the Mayflower to cross the Atlantic), who would let sick people aboard? And notwithstanding that, 10 weeks on a small boat that lacked any scintilla of modern sanitation would be long enough for a sick person to infect everyone else — and for everyone to either recover or die. I thus have a real problem believing that there were contagious Europeans coming ashore.

But the larger question is from whom did the Europeans catch these diseases? Who was the “Patient Zero” in Europe and how was *that* person infected?

It’s widely known that viruses mutate, and that they sometimes “jump species” — as I understand it, AIDS jumped from monkeys to humans. We know that Lyme Disease is caused by the Borrelia bacteria and it was discovered in Lyme, Connecticut in 1975 — where was it before then? Yes, people in New England traditionally burned fields to kill ticks, but they had neither DEET nor DDT — they would inherently be bitten by them, which is why they went to the effort and risk of burning fields in the early spring.

It’s known that Europe had waves of quite lethal plagues — but where did those plagues come from? And how do we know that the same set of circumstances didn’t create equally lethal waves of plagues on this continent as well? Other than the presumption that all things European are inherently bad, I’ve seen no evidence to the contrary.

It’s also believed that viri tend to mutate toward less-lethal variants over time because dead hosts neither permit a virus to reproduce nor spread. In the early 18th Century it was widely known that people arriving from Europe would be sick for a week or two upon arriving here — I’ve seen it called the “New World Disease” and apparently everyone caught it.

So how do we know that this wasn’t the less-lethal mutant of a virus that had killed large numbers of Indians a century earlier? We know that large numbers of Pilgrims died that first winter, and we speculate that it was the lack of shelter & food that caused that — but we don’t know that…

It’s not like we had a modern CDC doing autopsies — medical science was still very much in the Middle Ages back then, and we didn’t really understand epidemics even a century ago — look at the mistakes we made with the Spanish Flu…

Hence absent real evidence of a type that we will never have, I am not willing to accept the presumption that the Indian mortality was caused by a European-introduced disease. In order to believe it, one would have to both answer the question of from `whom the Europeans caught it, and why whatever natural processes created it couldn’t also create something equally lethal here.

You mean the Wampanoags’ enemies, don’t you? (Second paragraph)