The higher education accountability movement has seen very little progress over the years. The main success was the establishment of Cohort Default Rates, which revoked financial aid eligibility for colleges where too many students defaulted on their student loans. But this was both obscenely forgiving (a college could only lose eligibility if 30% or more of its students defaulted) and short-lived—the emergence of income-driven repayment plans has rendered Cohort Default Rates obsolete, since, under these plans, students can make payments of $0 and still not be considered in default.

The lack of accountability is a problem. While most colleges offer a legitimate education at an affordable price, there is little stopping some colleges from offering an education in name only at inflated prices, paid for with federal student loans. And if the student later defaults on his debt, the college gets to keep all the money while saddling him with a lifetime of financial distress and taxpayers with a bill that will never be repaid.

While there has been too little progress on accountability, there is one bright spot that is consistently yielding innovative approaches to it: the progressive crusade against for-profit colleges using gainful employment.

If there is one thing progressives hate in education, it’s profits. Of course, not all profits are equally hated. Public and private non-profits don’t have shareholders, so they turn their profits into extravagant salaries and benefits for faculty and administrators. For example, the highest-paid private non-profit university president made $5 million last year, and the highest-paid public university president made $2.2 million. The average faculty salary for full professors at private non-profit doctoral institutions is over $200,000.

While this type of profit occasionally bothers progressives, it is for-profit institutions that really drive them mad. As a result, the last two Democratic administrations have scoured federal statutes for ways to shut down for-profit colleges. Their biggest opening is the requirement in federal law that vocational programs prepare students for “gainful employment.” The statute defines a vocational program as any program at a for-profit institution, as well as any non-degree public and private non-profit programs. Gainful employment is undefined, so by using regulation to impose a stringent definition, progressives have been able to target for-profits (with non-degree public and private non-profit programs as collateral damage).

The Obama administration took two swipes at defining gainful employment. Its first attempt was overturned in court because it would have required the Secretary of Education to approve any new program at a for-profit college (a massive expansion of federal interference in education), and because the repayment-rate threshold was chosen arbitrarily to ensure that a predetermined share of for-profit programs would fail. Its second attempt to define gainful employment survived court challenges and used two debt-to-earnings tests.

These regulations moved the Overton window for accountability in highly desirable directions. To begin with, the regulations sought to hold programs rather than institutions accountable (e.g., the bachelor’s in economics at Purdue rather than Purdue). This was a seismic improvement for two reasons. First, it avoided punishing good programs at bad schools or allowing bad programs at good schools to escape accountability (ironically, one of the programs that failed Obama’s gainful employment tests was a theater program at Harvard). Second, it used a scalpel rather than a guillotine. If you hold an institution accountable by withdrawing access to federal financial aid programs, you’ve essentially sentenced the college to death, since virtually no college accustomed to using these programs can survive without them. But if you identify the failing programs and cut off access for them alone, it is not an existential threat to the institution since the rest of the college can continue operating.

[Related: “To Fix Student Loans, Keep It Simple”]

The Obama administration’s second gainful employment regulations were also the first time that the government took post-graduation labor market outcomes into account. In particular, they looked at earnings relative to debt to assess whether the student loan repayment burden was affordable. While this is an obvious approach, the Obama administration was the first to actually implement it.

While these novel approaches to accountability were dramatic improvements, the Trump administration was right to rescind gainful employment. Its selective targeting was too blatantly driven by progressives’ ideological animosity toward for-profit colleges. First, similar programs were treated differently. A nursing program at a for-profit college was subject to gainful employment, while a nursing program at a private non-profit down the street was not. Second, when applying the gainful employment tests to all of higher education, I found that

by excluding degree programs at public and private nonprofit universities, gainful employment missed the vast majority of programs that leave their students with excessive student loan debt. Gainful employment identified only 611 such programs … whereas gainful employment equivalent identified 3,201 failing programs. If the goal of gainful employment (or successor accountability systems) is to protect students from programs where they accumulate excessive student loan debt, then focusing on any one type of college will miss too many problematic programs. For example, focusing just on for-profit colleges would miss 89% of failing programs and 73% of students graduating from a failing program.

Overall, the Obama gainful employment approach had some good ideas but botched the execution by only applying the enhanced accountability measures to ideological opponents.

The Biden administration is planning to implement new gainful employment regulations. While it is virtually guaranteed to repeat the Obama administration’s mistake of selectively targeting for-profits, it isn’t simply dusting off the old Obama regulations. The Biden administration has not yet released its full plan, but one idea it has floated is that of earnings floors. Programs would fail if graduates earn below some threshold (e.g., the earnings of the typical high school graduate).

This is a great idea, particularly if you add a safe harbor for programs that increase graduates’ earnings by a sufficient amount, even if earnings remain below the floor.

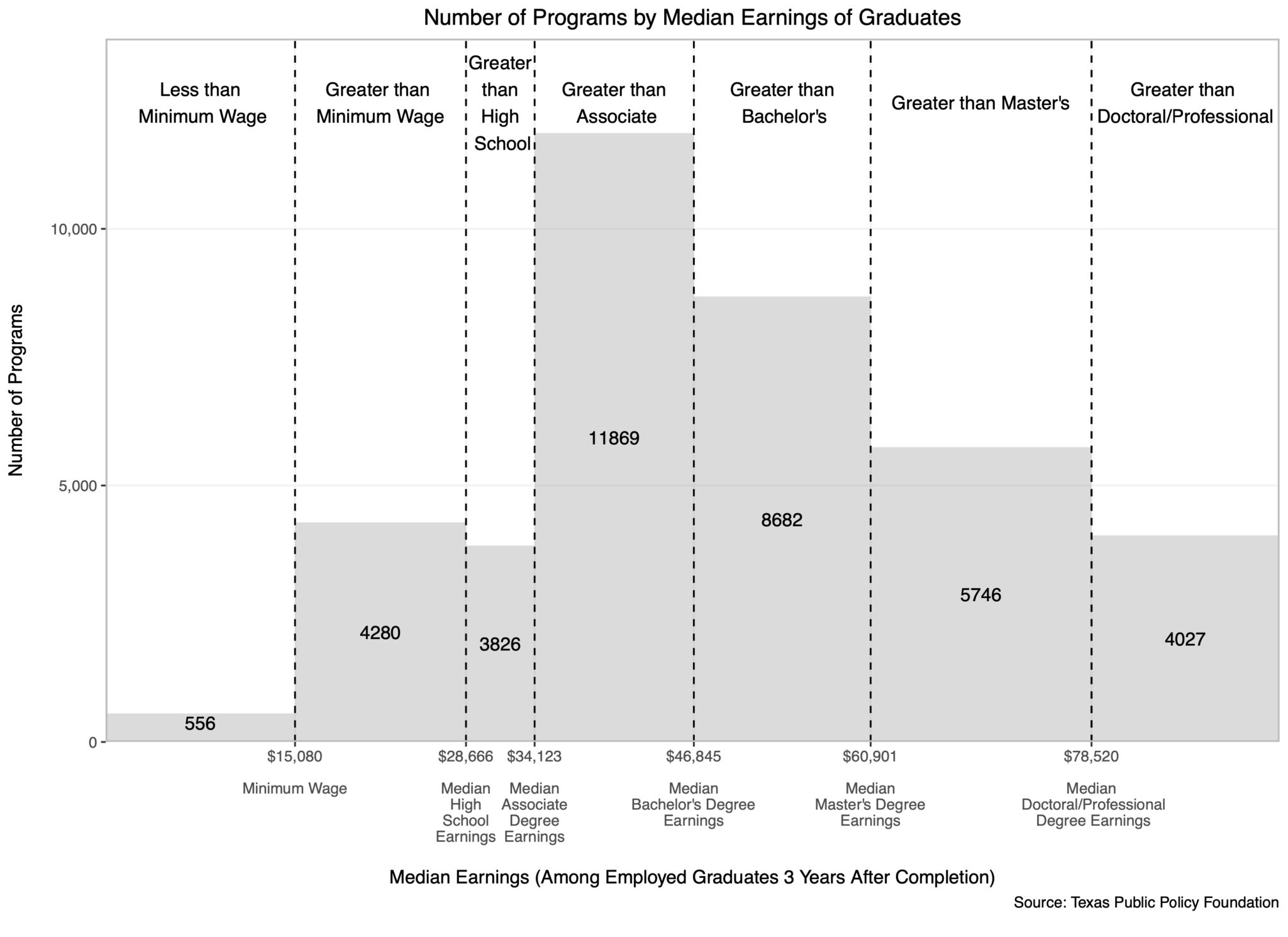

Earnings floors would spell trouble for a lot of programs in higher education. The figure below shows how many programs fall into several earnings brackets with natural thresholds.

Click Here to Download this Figure

There are 4,836 programs where the median graduate earns less than the typical high school graduate. This includes over a thousand bachelor’s degree programs. While some of these are not shocking (e.g., 134 are fine and studio arts programs, and another 81 are drama programs), there are plenty of surprises, including 19 nursing programs, seven philosophy programs, and even a computer science program. The point is that it isn’t the major that identifies excessive financial risk for students, but the labor market outcomes. There are more than 300 fine and studio arts programs where graduates have higher earnings than that computer science program, which means the accountability focus should be on earnings, not the academic field.

[Related: “Dos and Don’ts for Higher Ed Accountability”]

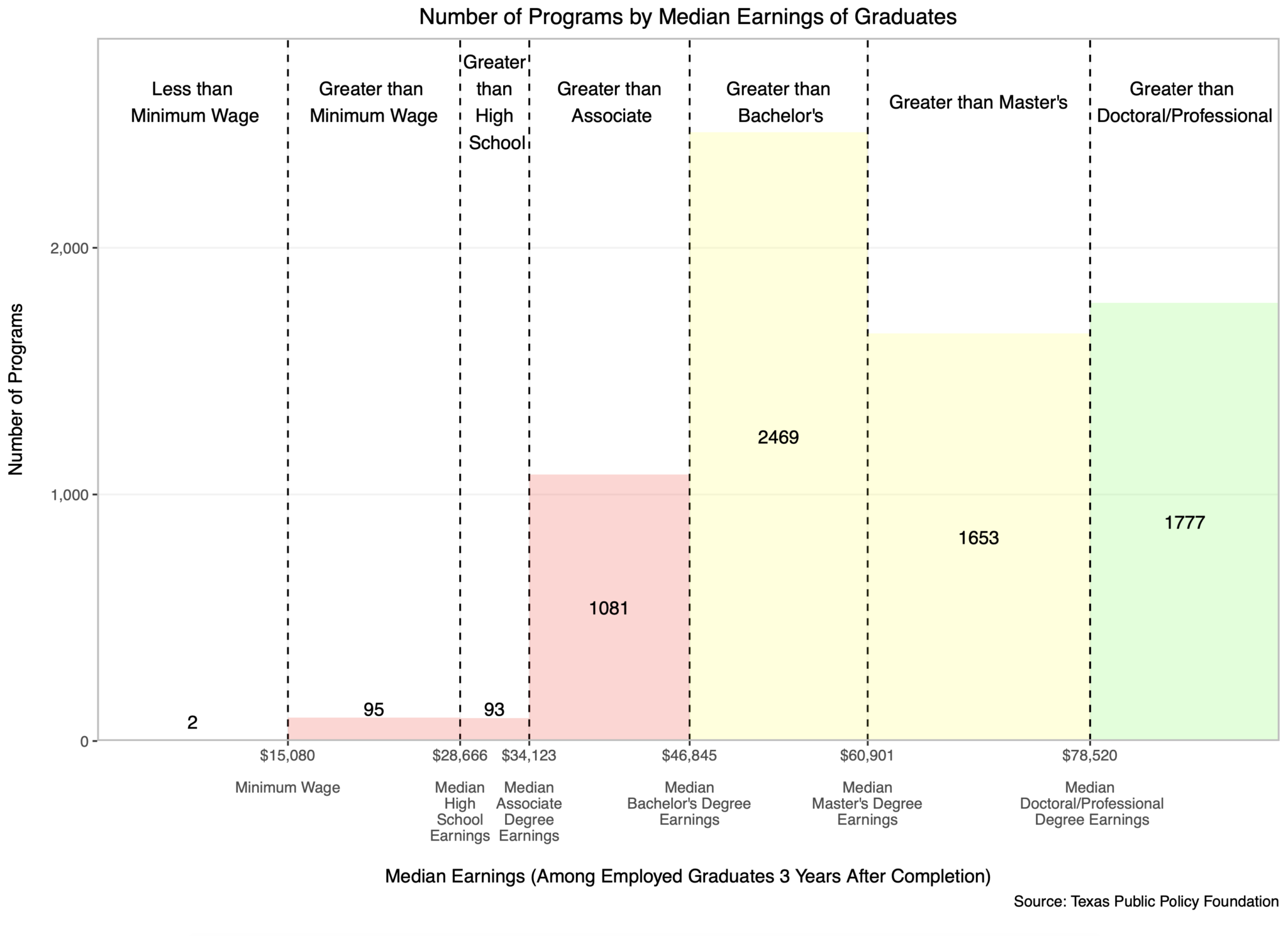

The floor should also vary based on the credential. A natural choice would be to use the median earnings of the preceding credential as the earnings floor. For example, the earnings floor for master’s degree programs would be the median earnings of bachelor’s degree recipients. The figure below shows the results of using this floor for master’s degree programs. There are over a thousand master’s programs where the typical graduate earns less than the median bachelor’s degree recipient. These programs should face enhanced regulatory scrutiny, and many of them should lose access to student loan programs. Conversely, any master’s degree program where the typical graduate earns more than the median earnings of professional/doctoral degree recipients should be rewarded with regulatory waivers or additional funding.

Click Here to Download this Figure

Unfortunately, the Biden administration is likely to botch the implementation of gainful employment. It will repeat the Obama administration’s mistake of selectively targeting for-profits (with some public and private non-profits’ certificate programs as collateral damage). And it seems likely that the Biden administration will use a single earnings floor that applies to all programs, which, in practice, will function as a get-out-of-jail-free card for most graduate programs.

This means the next Republican administration will have two tasks. First, stop the implementation of Biden’s gainful employment regulations. Second, salvage any good ideas from the effort and apply them to all of higher education.

Image: Adobe Stock

I purchased a WordPress theme from PHP Souq, and it works perfectly! Highly recommended for developers and designers.

There’s a point being missed here — the opportunity cost of the years spent in college and the pay raises which the person would have received during those years. Hence it shouldn’t be a comparison to a high school graduate but to a high school graduate who had been employed for the past four years, with similar adjustments made for masters and doctoral programs.

On the flip side, we gotta think about women having children — if for no other reason that we *need* intelligent women having children or the future of this country is kaput. The absolute worst thing we could do is punish institutions that such women attend — and their education is NOT “wasted” if they decide to have children before using it.

I’m thinking of a woman who had essentially been engaged since the spring of her freshman year, and who graduated with a 4.0 GPA back when it wasn’t easy to do that. She married the August after graduation and proceeded to have three children with her husband supporting the family. She said at the time that she “was doing the mommy thing.” And now in her early 50s, she has a responsible (and I presume lucrative) position in her undergrad field.

And the flip side of this is my (male) MD — someone with jaw-dropping credentials at a respected medical school, highly respected as a MD, and who took paternity leave when his daughter was born…

I don’t know how we adjust for this, but I think we kinda have to lest we wind up in the situation Japan currently is. And Europe is. And even China is — we *need* children. And penalizing a university that is friendly to women who wish to “do the mommy thing” would also be sabotaging our own political interests….