Neapolitan Overtime

What is a constitution? In the very broadest sense, whether we refer to Moses’s ten commandments (1450 BC), the Magna Carta (1215), or the Articles of Confederation (1777–89), a constitution is a document that defines and reflects the existence of a people or a nation. A constitution doesn’t have to be a specific written event, but like a religion it suggests a singularity of some sort. Like the people who embrace it, a constitution emerges from some previous social order. There’s a before and after to most constitutions. Oftentimes, a great war, revolution, or migration calls a constitution into existence. Still, some constitutions have evolved gradually, building up over time as a set of rules and practices that a society lives by. Even a written constitution carries a plethora of epiphenomena (procedures, terms, writs) that are all constitutional in nature but not necessarily recorded anywhere in the ruling document.

Some people think a constitution should make the world right. They have a long list of positive things that a constitution should do, grant, or mandate. I think, rather, the world gets set right mostly by way of informal arrangements or individuals acting on a daily basis in their own and each other’s interests. Even when a constitution plays a role in improving life, it often does so in an indirect, subtle, or gradual way. It might allow people to be more efficient or facilitate already existing options which have been shown to work.

This is to imagine a constitution in the liberal fashion, along the lines of what Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay had in mind around 1787. Constitutions cannot dictate that life will be devoid of pain or conflict. This is especially true in politics. Factions or teams are bound to take shape, even among people who speak the same language and share the same religion. The trick is to coordinate these factions and get them to play with each other, albeit in the very serious sense of Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (1938).

Alexis de Tocqueville knew that a nation’s constitution can neither hide nor avoid conflict. He also saw external benefits that come with the responsibilities and independence required of citizens living under liberal constitutions. He saw the wonder of a constitution that promotes “subsidiarity” or local decision making whenever possible. Solutions formulated closer to the sites of problems tend to use more and better information. Local fixes are more likely because the parties know each other and understand the circumstances of the issue they want addressed. Finally, subsidiarity promotes learning and adaptation by citizens who do not rely on far away politicians to make decisions.

One of a constitution’s best effects is educational. Jury duty, for example, which is instituted by the Constitution, teaches people about their rights and shows them why they should want to keep them. It does this in ways that a school cannot. This is why a constitution should be imagined as a traditional playground rather than a traditional school. And you want a Montessori constitution, not a Stalinist one. Instead of granting rights, it should establish some basic rules and then get out of the way. Ideally, play will then become self-directed and rarely need a referee. Finally, some amount of bumping and bruising must occur. Otherwise, the game becomes insufferably slow and nothing happens. In the hypothetical case that all contact is forbidden, so many whistles and cards might mean that some players never touch the ball.

[Related: “Sum, ergo cogito: ‘I am, therefore I think'”]

A positivistic constitution is often a slippery slope that reveals Tacitus’s dictum that the injustice of a government is proportional to the number of its laws. On the one hand, since positive rights are in effect a type of regulation, they grow bulky and interfere with the game. They also pit people against each other. Laws which grant rights to some start to impose the costs of those rights on the rest of us. Finally, lists of laws stupefy people into obeying orders and at most just lobbying the government for what we want. They create the nanny state’s dream of perpetual dependency. This brings play and growth to a halt, which limits our ability to flourish.

The Chilean constitution which came out of a convention held between July 4, 2021 and July 4, 2022 is an example of an overly positivistic constitution. Most of its 388 articles distribute rights and responsibilities like candy going out of style. It was thankfully rejected by a margin of 62% to 38%. The Chilean people appear to have recognized the constitutional monstrosity as an example of Tacitus’s dictum. There is reason for optimism, then. It is also true, after all, that the Chilean people previously created and lived under one of the world’s most successful constitutions. Perhaps they can do it again.

*

The game of soccer is a lot like Latin America. It’s already an exciting and beautiful game, and one gets the impression that a few small changes in the rules would make it even better. If done right, this might even attract more fans, i.e., more people might want to join the great and growing Republic of Soccer instead of turning to basketball or football. The latter sports are boring for a variety of reasons. I want no truck with them. Baseball is another matter, but I will leave that discussion for another day.

As I see it, the problem with soccer is that it too quickly gives up on the possibility of allowing a proper victory. We all know a professional match shouldn’t end in penalty kicks. This introduces unacceptable doses of luck into a sport that is otherwise nearly perfect. Why do this? Why flip a coin to decide who gets sacrificed to the gods of soccer? We know in our hearts this is wrong. It’s worse. At critical moments, soccer incentivizes playing for a tie. This is to say that, under certain conditions, the rules of soccer disincentivize winning.

I remain committed to my Mexican friends on this matter. I have written repeatedly to the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) asking them to consider a better alternative to penalty kicks if an important match ends in a tie. In America, every season brings changes to the rules of baseball, football, and basketball. I think soccer could be improved by implementing what Americans will recognize as a “sudden death shootout,” also known pejoratively in rural Virginia as “Neapolitan overtime.”

The disrespectful connotations of Neapolitan overtime owe to a now legendary game played between the Republic of Ragusa and the Kingdom of Naples on February 8, 1806. The ball game in those days was nothing like modern soccer. The name alludes not to the game itself but to the type of overtime played that day. A majority of players on both sides must have wanted to tend to more urgent matters. Whatever the cause, changes in the rules had to be instituted on the fly so as to both resolve the game and shorten it. There might not have been another game for a long time, and a tie would have been unacceptable to both sides.

“Neapolitan overtime” creates an extra period while also decreasing the size of the field of play and removing players from each team at fixed intervals. The phrase’s insulting usage arose almost overnight when the losing Ragusan side claimed that the improvised rules had favored the Neapolitan style of play.

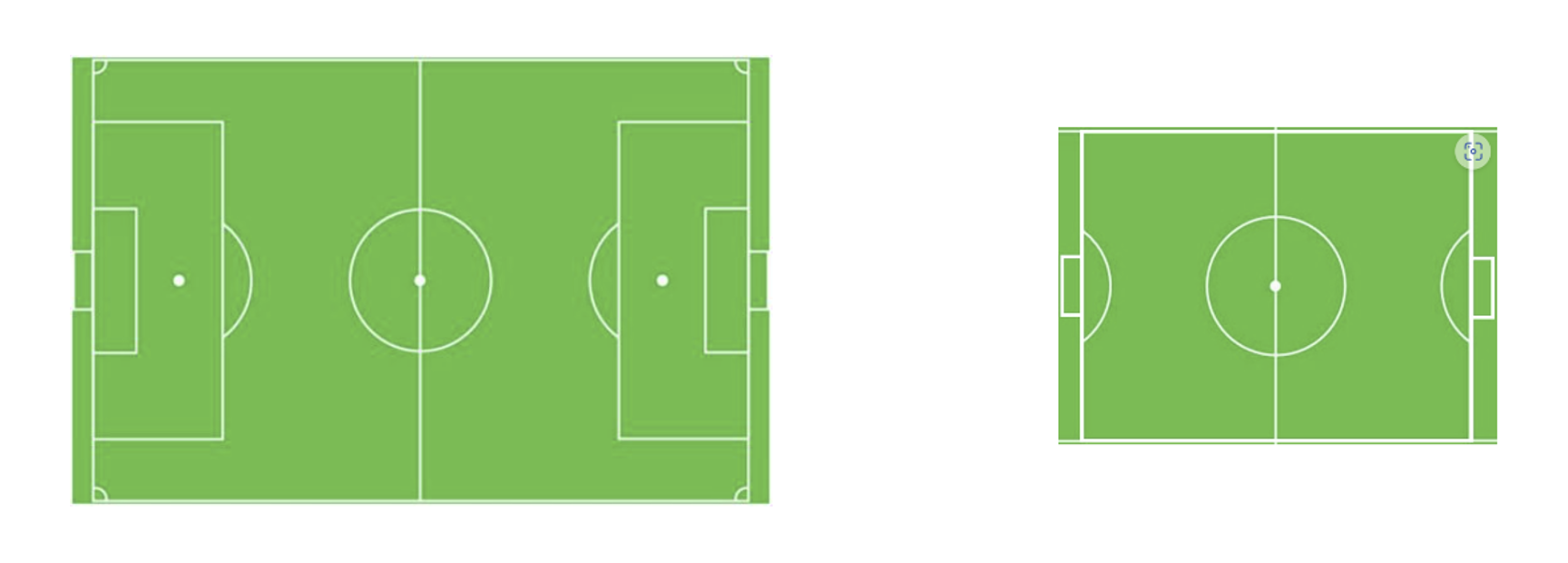

Traditional Soccer Field vs. Neapolitan Sudden Death Field

The Neapolitan solution to modern soccer is simple. During a sudden death shootout, the size of the field of play is shrunk by about two thirds (see diagrams). Additionally, a player from each side is eliminated every three minutes. So, when an important match is tied after ninety minutes, the goals are moved forward and placed on the penalty box line. The penalty box line becomes the new goal line, and the penalty arc functions as did the penalty box. The only adjustment to the pitch is that the side lines of the penalty boxes must be produced out to the half-way line, making for new touchlines. The referees can do this in less than five minutes between the end of regulation play and the beginning of a sudden death shootout.

The first team to score wins in Neapolitan overtime. The pitch is now roughly a third the size of the original, so goals will be easier to score and the game’s pace will increase. Moreover, as players are removed every three minutes, the game will spiral toward a frantic climax. Each team picks which of its players are eliminated. Thus, if the game is still tied after an additional thirty minutes of play, fans will witness an epic “one-on-one” encounter between the two best players from each side. After a tie in a championship match, an entire season could conceivably come down to this final showdown between the two best players on earth.

[Related: “What is a Nation-State?”]

Imagine, if you will, a mythical match between Madrid and Barcelona in which, after two regulation periods of sixty minutes each, and after thirty minutes of a sudden death shootout with eliminations, everything boils down to Lionel Messi versus Cristiano Ronaldo. Mind you, the score can still be tied three minutes later, but play no longer pauses to remove anyone. At some point the game will end the way that it must.

This change would occasion a new skill set. A new type of specialist player would emerge, and new stats would be needed, resulting in new ways of evaluating and discussing each team’s chances. Finally, Neapolitan overtime would allow Americans to enjoy soccer because games would no longer end in such a pathetic manner.

I trust I don’t have to explain to FIFA yet again what an increase in American viewers would mean for soccer. They should rename their organization the Fédération Internationale de Soccer Association (FISA). I’ve never received any response from FIFA regarding the Neapolitan shootout. They should at least allow me to circulate a survey among the players of the top European teams in order to measure their openness to this reform.

Like good writing, a more precise and significant game of soccer probably remains an illusion. Cervantes set aside a special place in hell, just inside the gates (DQ 2.70), where devils play an odd form of soccer with imaginary texts instead of real balls. One of the texts in play is the novel itself. Nobody gets hurt, and the novel gets written. The novel genre might be a particular kind of constitution, a moral or social epiphenomenon that works to help society work through their difficulties in more mysterious ways.

Thucydides relates the type of societal decay that ends in hell, or what he calls stasis, to the appearance of linguistic games and other public shenanigans. The climax of the Peloponnesian War corresponds to various cases of something resembling the instability of novelistic discourse. It is fascinating to think that, as the whole Greek universe collapsed over the course of the fifth century BC, Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides wrote history’s greatest tragedies.

Changes have happened in cultures and nations over the centuries which still determine what kinds of societies we have, what our politics are like, and what kinds of rules we live by. Personally, I want laissez-faire capitalism and a constitutionally limited presidential republic with an executive chosen by a national lottery. Neither will happen in my lifetime in the U.S. However, it’s still interesting to think about which changes to the rules might promote a capitalist republic. Chile is already a strikingly successful constitutional republic by most regional and international standards. What kind of constitution would make it even better?

Image: Hossein Zohrevand/Tasnim News Agency, Wikimedia Commons

“he game of soccer is a lot like Latin America”

Yes, never forget that El Salvador & Honduras went to war over a soccer game.