The Academic Bill of Rights revisited

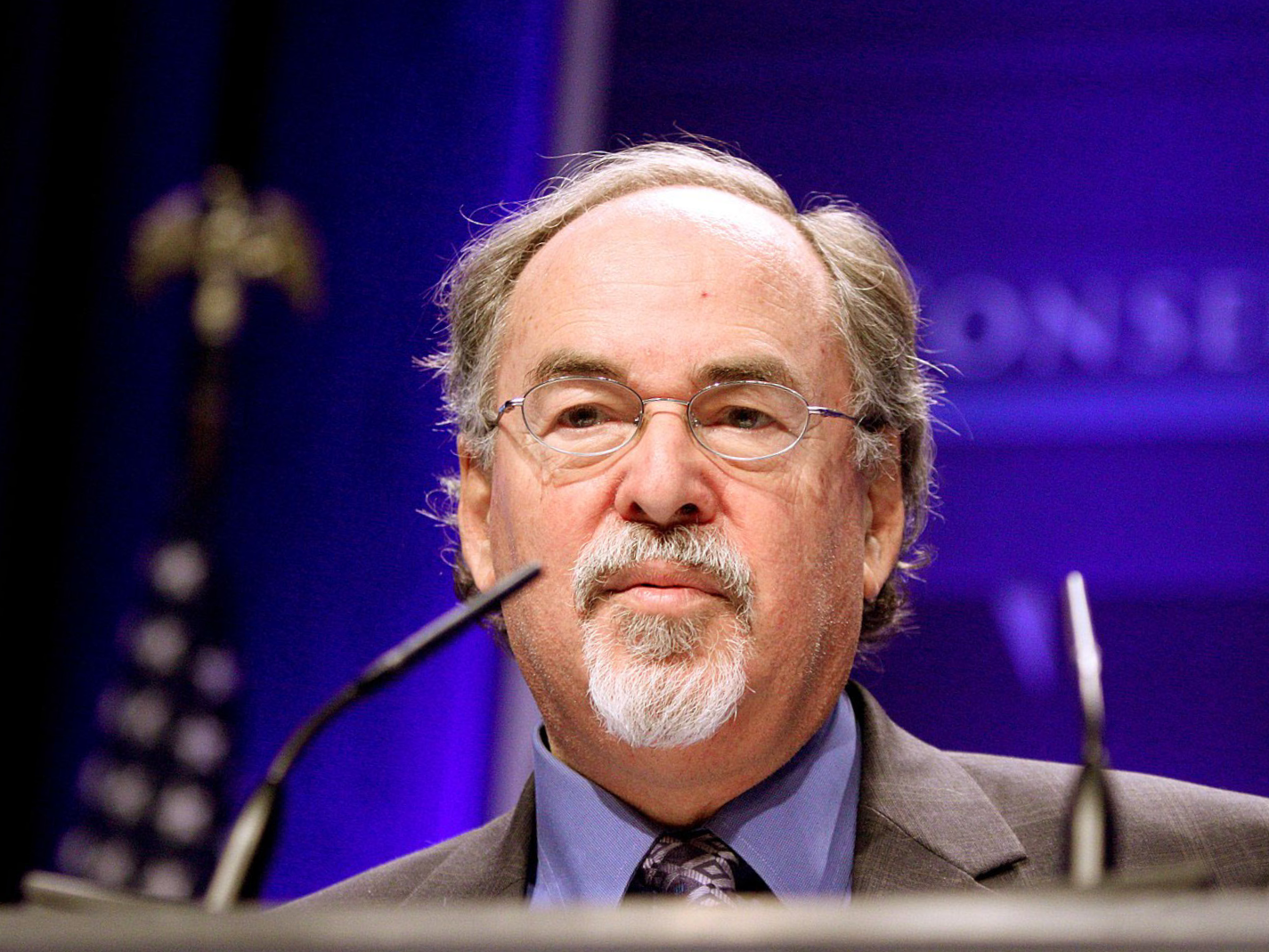

David Horowitz is a controversial fellow. Born into a communist family in New York and involved early on with the Black Panthers, he remained on the Left until he was repulsed by the murder of a woman friend, a killing for which he held the Panthers responsible. He describes this transition in his book Radical Son (1997). Now Horowitz is routinely demonized as an Islamophobe, a right-wing extremist, and even, according to right-identified but New-York-Times-compliant commentator Bret Stephens, “something of a Stalinist.” So, whether Stalinist or fascist, David Horowitz has had a hard time being taken seriously—defectors are never treated well.

Horowitz is both clear and provocative. He sometimes seems to attack unfairly. He has been accused of cherry-picking his targets. But clarity may be his main problem. I noticed years ago that many academics are as offended by the kind of prose which they read as they are by the position it takes. Ad hominem argument is widely accepted, but clarity itself often offends. Consequently, even perfectly reasonable proposals from Horowitz elicit knee-jerk opposition—even from groups that one might expect to agree with him.

A striking example is the Academic Bill of Rights (ABOR) that Horowitz proposed in 2004 “in response to a growing concern that modern university curricula have become overly political and ideological.” John Ellis reviewed the ABOR in a penetrating 2011 Academic Questions article, pointing out how Horowitz had successfully exposed the utter hypocrisy of institutions, such as the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), that claim to protect academic freedom and free inquiry while actually doing the opposite:

What Horowitz’s ABOR campaign has done is to force the other side to declare itself. It says, in effect: very well, if the problem is really as insignificant as you say it is, you should have no trouble in subscribing to some very simple, innocuous language that says that hiring and grading should be free of political discrimination, and courses should carefully analyze complex issues rather than simplify them through omitting everything that might impede proselytizing for one side.

Not only did the AAUP and allied organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union reject the “innocuous language” of the ABOR, but they also viciously attacked it and its author. Horowitz has continued to publish provocative books and is still stigmatized by academic organizations. But the ABOR and the response it elicited should not be forgotten. The comments that follow are a footnote to Ellis’s analysis and a reminder of the problems the academy still faces.

The text of the ABOR “is based on a famous document called the ‘Declaration of the Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure,’ published in 1915 by the American Association of University Professors.” Here is a key excerpt from the 1915 declaration:

The university teacher, in giving instructions upon controversial matters, while he is under no obligation to hide his own opinion … should … set forth justly, without suppression or innuendo, the divergent opinions of other investigators; he should cause his students to become familiar with the best published expressions of the great historic types of doctrine upon the questions at issue; and he should, above all, remember that his business is not to provide his students with ready-made conclusions, but to train them to think for themselves, and to provide them access to those materials which they need if they are to think intelligently.

“These principles have long since been incorporated into the academic policies of most American research universities,” wrote Horowitz. What’s not to like?

The AAUP was not flattered: “Not only is the Academic Bill of Rights redundant, but, ironically, it also infringes academic freedom in the very act of purporting to protect it,” they claimed. The AAUP’s beef was with the ABOR requirement that universities should try to establish “a plurality of methodologies and perspectives.” They have a (small) point. No university should require faculty to support a position that is known to be wrong—flat-earth physics or astrology, for example (not that the ABOR did). But these views should certainly be open for discussion, compared to others, and, if necessary, shown to be wrong. But what are you to do when many disciplines now do precisely the opposite: suppress discussion of unpopular positions that nevertheless make legitimate arguments? Current topics where dissent is risky include climate change, sex and gender, behavioral and cultural differences, and even archaeology. Where can these issues be openly discussed, if not in the academy?

[Related: “My Compelled Speech is Your ‘Academic Freedom’?”]

The AAUP avers (correctly) that a university should not control the relative number of Republicans and Democrats on its faculty. But the reason Horowitz counted these two groups was simply to suggest that there exists an unusual level of political unanimity among faculty, an asymmetry which has only grown since 2004. It is hard to dispute that this disproportion makes it easy to downplay, and eventually exclude altogether, ideas perceived as contrary to a progressive consensus.

Classical-liberal and pro-capitalist points of view are most at risk. I remember discussing these issues some years ago with a distinguished and widely read (I thought) postmodernist scholar, only to find that she had never heard of Friedrich Hayek. She was, however, well acquainted with Gramsci, Derrida and Marx. Inevitably, her students were denied exposure to legitimate contrary views.

One response to the ABOR, published in the AAUP’s ironically named Journal of Academic Freedom, (2014, vol. 5), was written by Adria Battaglia, a professor of rhetoric at Angelo State University. In “Opportunities of Our Own Making: The Struggle for ‘Academic Freedom,’” she presents a lengthy diatribe attacking Horowitz, purporting to demonstrate “how the link between ‘academic freedom’ and ‘free speech’ becomes a rhetorical strategy by which we can gain political and economic legitimacy.” The word “legitimacy” gives her away. In the academy, all views should be open for discussion, from Marxism to libertarianism. It is not the business of a scholar to delegitimize any but direct attacks on academic values: the issue is not legitimacy but truth. Without a belief in truth, real science is impossible. Yet many subdisciplines of sociology, for example, attack the idea of truth itself: “the devil of objectivity,” “multiple truths,” “personal truths,” “white logic,” etc. These attacks go uncensored. Yet in scholarship and science—Wissenschaft—an attack on truth is illegitimate and should be proscribed.

Battaglia freely attributes sinister motives to her target: “[activists] historically have sought ways to divide, delegitimize, or dissuade political participation that questions institutional legitimacy. David Horowitz is just such a political strategist. … Horowitz [is mobilizing] a political campaign in a cultural war. … Horowitz adopts the camouflage of ‘freedom’ in order to make headway among academic administrators and legislators …” Ad hominem ad nauseam.

Now the AAUP argues that:

A fundamental premise of academic freedom is that decisions concerning the quality of scholarship and teaching are to be made by reference to the standards of the academic profession, as interpreted and applied by the community of scholars who are qualified by expertise and training to establish such standards. … When carefully analyzed, therefore, the Academic Bill of Rights undermines the very academic freedom it claims to support. … The AAUP has consistently held that academic freedom can only be maintained so long as faculty remain autonomous and self-governing.

This sounds reasonable, but it does not consider the fact that the modern ‘university’ really isn’t universal at all. There are no “standards of the academic profession” to which all agree. There is not even a consensus on truth-seeking as a core value.

Social science, for example, has subdivided into more than one hundred subdisciplines, each with its own political spin and standards of evidence that are essentially immune to criticism from others. A consequence of this fissiparousness is that views that are either absurd (“sex is a spectrum”) or blatantly political (“color-blind racism”) can flourish in their own little hothouses, shielded from independent criticism. (These and other threats to the unity of science are documented in my book Science in an Age of Unreason.) Can such a Balkanized and politicized faculty be trusted with total autonomy? Some checks and balances are needed.

AAUP author John K. Wilson begins his comment on a subsequent Horowitz book (One-Party Classroom (2009), with co-author Jacob Laksin) with a lie: “[the book] expands upon [Horowitz’s] long-running war on academic freedom [emphasis added].” Wilson went on to accuse Horowitz of trying to impose a “vast repressive apparatus,” of having “vast political influence on the far-right,” and, thus, of creating “an atmosphere of fear.” And “[Horowitz] objects to women’s studies classes dealing with the ‘unproven’ claim that gender is socially constructed, apparently unaware that biology is not the sole determinant of gender differences.”

[Related: “The Conspiracist Fantasy of University Bureaucracies”]

Well, gender and sex are now defined differently, but it was not always so. Fans of the “spectrum” idea also confuse sex and gender: many women’s studies programs seem to be unaware of biology, for example. (I recall that in my own university, when a supposedly “interdisciplinary” women’s studies program was instituted many years ago, biology was, in fact, one of the few disciplines not represented.) Horowitz has argued that “An open academic inquiry would not be ‘for’ or ‘against’ anything” and would be agnostic about all values save “truth,” a claim with which many scientists and philosophers, from David Hume to Charles Darwin, would surely agree. But Wilson, along with a majority of sociologists, thinks it is fine for academics to advocate political causes as part of their teaching. The difference between teaching and indoctrination now seems to elude many academics.

I could go on. The point is that David Horowitz has been effectively marginalized as a right-wing extremist—hence, his suggestions can be ignored. But sometimes they should not be. His most recent book, Internal Radical Service, with co-author John Perazzo, makes a simple point: dozens of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) violate the terms of their tax-exempt status by directly or indirectly supporting political causes. The book reprints multiple sections from the Internal Revenue Code that Horowitz and Perazzo think are routinely violated by dozens of NGOs. For example:

Under the Internal Revenue Code, all section 501(c)(3) organizations are absolutely prohibited from directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for elective public office. Contributions to political campaign funds or public statements of position (verbal or written) made on behalf of the organization in favor of or in opposition to any candidate for public office clearly violate the prohibition against political campaign activity [emphasis added].

These prohibitions seem pretty explicit, but the authors provide many examples where they seem to be violated by ostensibly charitable organizations. The best-known example is Mark Zuckerberg’s $400+ million donation to two left-wing tax-exempt foundations, which may have tipped the scales in Biden’s favor by launching ‘get out the vote’ campaigns focused on democratic precincts in battleground states.

Do these, and many other examples in the book, constitute a failure by the IRS? I don’t know, but perhaps some public-interest-law organizations should take a look.

Unfortunately, they are unlikely to do so because Horowitz has been so very effectively stigmatized. His reputation is unlikely to be helped by his entertaining new book, The 20 Dumbest Hollywood Hatemongers, which includes Jane Fonda (communism is great), Michael Moore (America was founded on the backs of slaves), and Robert De Niro (“F**k Donald Trump”). Laugh, but don’t ignore David Horowitz. He still has much to teach.

Image: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

“…it does not consider the fact that the modern ‘university’ really isn’t universal at all.”

The “university” has never been universal.

“Social science, for example, has subdivided into more than one hundred subdisciplines, each with its own political spin and standards of evidence that are essentially immune to criticism from others.”

Cant in so many ways. There are not 100+ social science disciplines. But I am willing to be persuaded otherwise. I’ll even make it easy for you. Please list 50 of these disciplines and the universities that house departments for them.

Each social science does not have its own political spin and standards of evidence. Some social sciences are so internally fragmented that it’s meaningless to talk about them as unified fields of study.

I dropped out of the AAUP years ago. They are just (another) extreme leftist organization in academia. My monthly “dues” are instead put into the university’s general scholarship fund.

I stand by my comments quoted in this review, and find it strange that Stoddard accuses me of a “lie” in claiming Horowitz wants a war on academic freedom. In fact, Horowitz routinely argues for repression, whether it is calling for a ban on Palestinian student groups, calling for IRS to suppress nonprofit liberal groups (even while Horowitz personally profits from his own explicitly partisan nonprofit group), or seeking to ban political expression in the classroom. Horowitz cynically took the AAUP’s language of ethical ideals for how professors should act, and tried to have legislation passed to enforce these norms. It’s quite reasonable for the AAUP to urge professors to be respectful of others, but it would be far different to punish faculty for disrespecting the government by engaging in political criticism.

“The term “academic freedom” has traditionally had two applications – to the freedom of the teacher and to that of the student, Lehrfreiheit and Lernfreiheit.”

AAUP General Declaration of Principles, 1915.

Lernfreiheit has been forgotten over the past century.

From the 1940 AAUP Statement on Academic Freedom (emphasis added).

1: Teachers are entitled to full freedom in research and in the publication of the results, subject to the adequate performance of their other academic duties; but research for pecuniary return should be based upon an understanding with the authorities of the institution.

2: Teachers are entitled to freedom in the classroom in discussing their subject, but they should be careful not to introduce into their teaching controversial matter which has no relation to their subject. Limitations of academic freedom because of religious or other aims of the institution should be clearly stated in writing at the time of the appointment.

3: College and university teachers are citizens, members of a learned profession, and officers of an educational institution. When they speak or write as citizens, they should be free from institutional censorship or discipline, but their special position in the community imposes special obligations. As scholars and educational officers, they should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution.