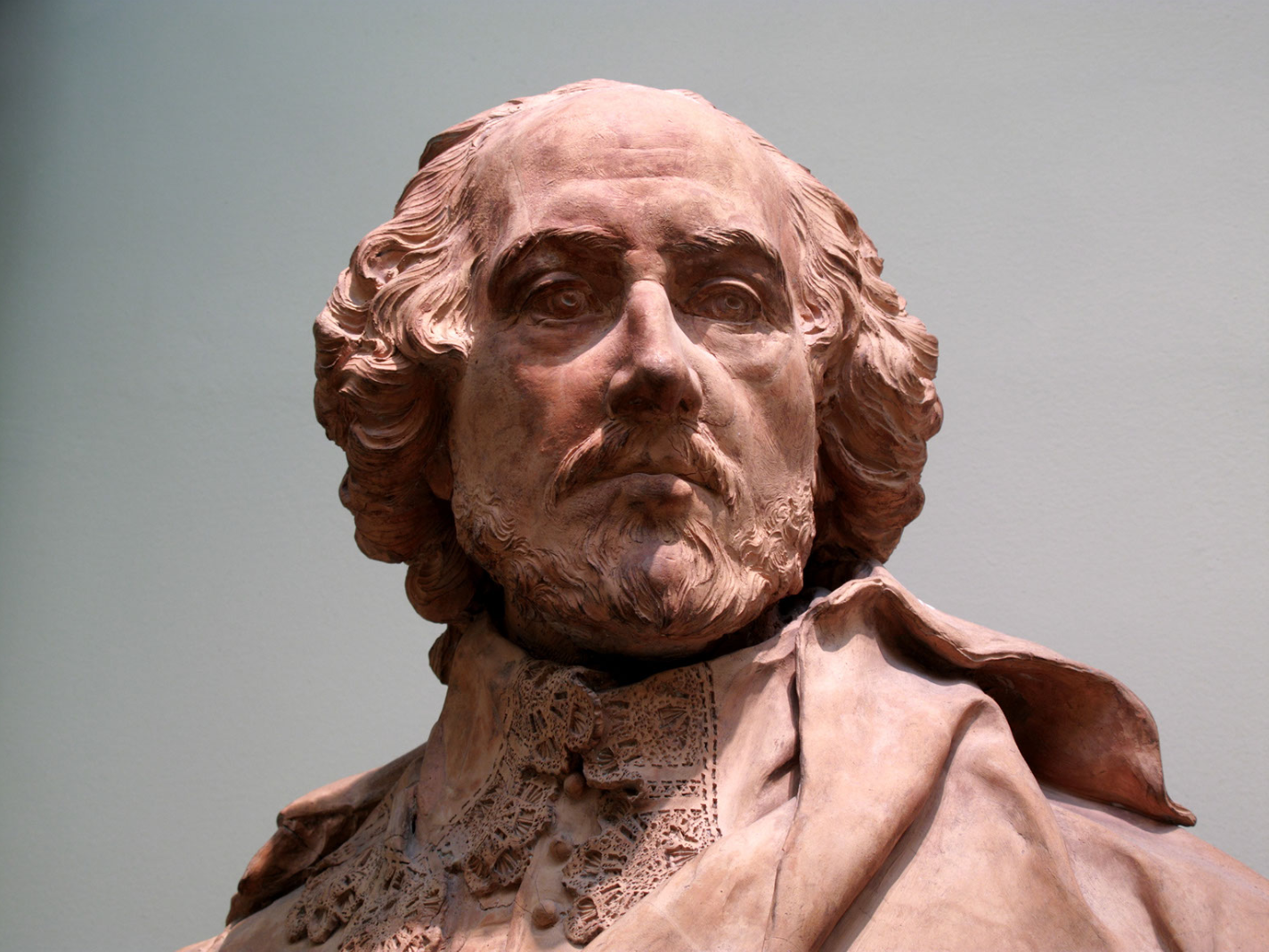

I always thought that William Shakespeare was a bit too harsh when, in Henry VI, Part 2, he said “Let’s kill all the lawyers.” Given the antics of our nation’s leading law schools and the American Bar Association (ABA), however, perhaps Shakespeare was onto something when he penned those words over four centuries ago.

In November, many of the nation’s top fourteen law schools announced that they would not participate in the annual U.S. News & World Report rankings, while the ABA gave notice that it will likely stop requiring the law schools it accredits to require standardized test scores for admissions. In short, they advocate providing both students and law schools with less information useful to determine who is fit to practice law in the United States.

Regarding rankings, as a Yale Law School graduate and friend of mine put it, Yale started things off in “A very Yale-like way” by announcing it was not going to participate in the U.S. News rankings. Not ten words into the press release, Dean Heather Gerken noted that U.S. News is a “for-profit magazine.” The horror! The unstated implication was that this magazine, whose owners selfishly pursued their own financial interest, was judging not-for-profit (and therefore morally upright) law schools. She added that the rankings “deincentivize programs that support public-interest careers,” namely altruistic lawyers who want to serve the public good by working for government or other worthy non-profit organizations, instead of those selfish and unsavory law firms which enhance corporate greed. I would note, however, that “for-profit” capitalism has provided a large portion of Yale’s annual income.

[Related: “Breaking Up the Law School Monopoly: Part 2”]

Yale’s move is particularly significant because U.S. News has, since it started its law school rankings, always ranked Yale the top school in the country. Its closest rival, Harvard, quickly joined Yale in withdrawing from the rankings, leading a large number of other highly regarded law schools to follow. The law school message seems to be: “the forces of justice will prevail! That selfish magazine is not going to keep us from achieving our noble mission of turning out ‘public interest’ (as opposed to ‘private interest’) lawyers who work to remove injustice and promote the common good.”

I look at this as a veteran observer, as an economist who has given expert witness testimony in dozens of courtrooms, and as the founder of the college rankings for one of U.S. News’ top rivals, Forbes. Also, I have long known and greatly respected U.S. News’ leading ranking guru, Robert Morse. We have attended meetings together on college rankings at places as far away as Kazakhstan.

There is another dimension to the story. Yale and other top law schools have been strong advocates for woke nostrums ostensibly designed to create a more just society. Dean Gerken lists on her vita her service to not one but two Barack Obama presidential campaigns. The dean of another Ivy League law school, Theodore Ruger of the University of Pennsylvania, is fighting to fire one of his most distinguished scholars, Amy Wax, for unforgivable sins such as suggesting that some persons are far more capable of performing well in law (and, by extension, in life) than others, and that perceived individual inequities are to be expected and even desirable.

Magazine rankings do provide useful information. U.S. News’ rankings are determined by such performance-based criteria as peer assessments of law school professors, deans, lawyers, and judges (40 percent), future employment and bar-passage rates (21 percent), debt incurred (5 percent), various selectivity measures (21 percent) like LSAT or GRE admission test scores or undergraduate grade point averages, and faculty and library resources (13 percent). All of these strike me as reasonable criteria to be used in assessing law schools, even if I might differ somewhat on the emphasis to be placed on each factor.

[Related: “Don’t Ignore Shakespeare’s Dick”]

At least one news account suggests that Yale’s decision may have been motivated by something other than altruism, namely the fear that it was going to lose its top ranking because of a decline in peer assessments. That assessment decline was likely caused by Yale’s apparent intolerance of some speech inconsistent with its woke mission. Along the same lines, several federal judges have said that they would no longer offer clerkships to Yale Law graduates, a potentially large blow to student professional success.

Legal wokeness is not confined to New Haven or the Ivy League. The accrediting council of the American Bar Association recently voted to stop requiring the law schools it accredits to require LSAT or GRE scores for admissions. The Law School Admissions Council, which administers the LSAT, argued that making admissions tests optional would result in admitting some students unprepared to succeed, ultimately hurting those students, the legal profession, and, arguably, the overall rule of law. While, theoretically, the accrediting body could be rebuffed by the ABA’s House of Delegates when it meets in February, the accrediting council ultimately determines policy.

In their zeal to reduce achievement gaps between races, sexes, and more, higher education is downplaying merit—the concept that those who are likely to do better should get the biggest rewards. This perspective has long determined most Americans’ vocational success. Rewards should be based on competence and achievement, not skin coloration, sexual preferences, religious orientations, family background, wealth, or other such characteristics.

Will the rule of law be weakened by creating lawyers without the academic background and the diligence needed to master constitutional mandates, statutory strictures, judicial precedents, or regulatory dictates?

Image: Adobe Stock

Just a thought/suggestion: there are many complex and nuanced issues to consider, not just taking a woke=bad angle on everything. I fully subscribe to your editorial line on this woke nonsense and gibberish. It’s alarming and depressing to see how this is blowing up the humanities. But being a bit less ham-handed and almost clownish (see the last 2 paragraphs of the article) about pushing this line will probably go further toward making your case.

Now please Rich let’s have mercy on Cotton DeSantis Hawley Cruz Bolton Hunter etc as well as the SCOTUS judges we all love so well.

Jonathan, I presume you oppose the ILLEGAL harassment that the SCOTUS justices have been (and continue to be) subjected to.

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2022/nov/11/justice-amy-coney-barrett-jests-about-pro-choice-p/

https://www.dailysignal.com/2022/11/07/tom-cotton-slams-merrick-garland-allowing-illegal-protests-supreme-court-justices-homes/

well yes of course

Shakespeare didn’t say “Kill all the Lawyers”. He put those words into the mouth of Jack Cade, a rebel odious in many ways.

Ignoring standardized scores as a measure of merit may be compatible with college instruction that is devoid of serious content in favor of desired attitudes and emotions.

Vedder writes:

In their zeal to reduce achievement gaps between races, sexes, and more, higher education is downplaying merit—the concept that those who are likely to do better should get the biggest rewards. This perspective has long determined most Americans’ vocational success. Rewards should be based on competence and achievement, not skin coloration, sexual preferences, religious orientations, family background, wealth, or other such characteristics.

Hard to believe this could be written in such an unqualified manner. Obviously, “merit” excluded women and minorities (read blacks) until a few years ago (within Vedder’s lifetime). Second, wealth is a huge determinant of success which in large part is determined by academic placement–there are more undergraduates at Harvard from the top 1% in income than there are in the lowest 60%.

This being said, competence is important, but competence is often in the eye of the beholder. Trump’s pocket judge in Florida developed a legal theory of embarrassment to protect him from a search warrant (fortunately overturned by the court of appeals)–is this competence? On the other hand, it is clear racial quotas have undermined competence to some extent–the lecturer fired from Georgetown law was simply stating the emperor had no clothes when she inauspiciously stated that about half the blacks were not at the level of the rest of the class–does anyone really believe she was racist?

So points from both sides. But Vedder, as an economist, is surely aware that our capitalistic society provides awards well outside of marginal product for many professions, helped along by government sponsored monopolies (he should read Friedman on regulation). This is not merit but political influence leading to restrictive laws (most laws on the restriction of the practice of law–requiring law degrees, or even actual practice–were put in place during the Depression to reduce competition). As a consequence, legal representation is unaffordable for most Americans were they need it most–consumer and domestic law. This doesn’t bother Vedder as he is part of the racket where a Ph.D. is required as an entry credential–academia. As a result college is now unaffordable.

Ummm, women already make up 54.9% of the students in ABA-approved law schools today.

I like the idea of abolishing the law school mandate. Let’s see how many students attend then…