Zig Ziglar, the late motivational speaker, wrote, “Check the records. All great failures in life are character failures, and all complete successes are character based. The need for character education is irrefutable.” Should Ziglar be dismissed out of hand because he was white? Character is a part of everything we say and do in life, and most parents are keenly aware of this.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. called for his children to be judged by the content of their character, he was calling for people to examine his children’s complete being as unique human persons created by God. There are still many who believe that King’s clarion call has not been achieved—therefore, the call continues to enjoy support from conservative Americans. Liberals, on the other hand, have moved from content of character to color of skin. In other words, the movement toward equality has been usurped by the push for guaranteed “equitable” outcomes, orchestrated by the government.

What Is Character?

Kevin Ryan and Karen Bohlin define character as “the sum of . . . intellectual and moral habits . . . the composite of . . . good habits, or virtues, and our bad habits, or vices, the habits that make us the kind of person we are.” The authors add that “good character is about knowing the good, loving the good, and doing the good.” One might ask, then, what is the good, and how can it be known, loved, and achieved?

Essentially, the authors contend that knowing the good is what Aristotle called “practical wisdom,” which implies knowing what type of thinking and action a situation would demand. Loving the good means “developing a full range of moral feelings and emotions, including a love for good and contempt for evil, as well as the capacity to empathize with others.”

Doing the good implies some form of the Golden Rule. It means, fundamentally, “respect for the dignity of others” and the shared values of the good that are a cross-cultural composite of moral imperatives and ideals that hold us together both as individuals and as societies. Those ideals that tend to cut across history and cultures are the Greek cardinal virtues: wisdom, justice, self-mastery, and courage.

One has to wonder whether competing perspectives are beneficial in subjective terms, or whether there is an objective standard of goodness that exists. Such a question cannot be answered by politics, because the best that politicians can muster is a semblance of bipartisan agreement.

Common grace is not arrived at by common agreement. That is called compromise, and it can be both productive as a legislation tool and destructive as a label when values are sacrificed. There is a strong connection between common grace and loving, knowing, and doing what is good. One need not be religious to demonstrate these. Thus, there is an affinity between common grace and character.

[Related: “The Exhaustion of ‘Antiracism’: Who has permission to quote MLK?”]

MLK and Christian Character

MLK was quite aware of the doctrines and virtues of the Christian faith, which are found throughout the Bible. His sermons presented these regularly. Love, grace, and character are hallmarks of the believer and were often repeated themes in MLK’s sermons. One example is 1 Corinthians 13:4-7 where the Apostle Paul writes:

Love is patient, love is kind, it is not jealous; love does not brag, it is not arrogant. It does not act disgracefully, it does not seek its own benefit; it is not provoked, does not keep an account of a wrong suffered, it does not rejoice in unrighteousness, but rejoices with the truth; it keeps every confidence, it believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things. (NASB; emphasis mine)

Christian character acts gracefully and does not keep an account of wrongs suffered. For many Americans, these elements alone are enough to disqualify the Baptist pastor with those who wish to hold to a moralistic legalism that casts past wrongdoings upon present generations. Grace releases. Legalism ensnares.

Positive character builds up. Negative character destroys. Grace is extended to others, so as to edify them and to call attention to the One in whom grace exists eternally. Focusing on skin color is temporal—it edifies self and is exclusive to members of a shared identity group.

When MLK spoke about the content of his children’s character, he was addressing all people. Certainly, his dream was a challenge to racist whites at the time. Horrifically, his life was cut short at age thirty-nine by an assassin’s bullet. After giving his life in search of equality and social justice for blacks, another generation has now decided to lay down the mantle of the past.

The current movement seeks justice as well. However, the ideology and the means by which the modern social justice movement pursues its goals lead to a radically different approach than that of Dr. King. Nevertheless, King’s call for character still resonates. It resonates from the annals of history and from the sermons of others across the land.

Character without grace is like living a virtuous life without understanding virtues. Justice for some, not for all, is another form of injustice. The real challenge is practicing grace when one’s character is tested. The real blessing of grace and justice is in a relationship with the eternal personage who grants them. This is echoed in the last portion of the 1 Corinthians 13 passage, which details what truly lasts: “But now faith, hope, and love remain, these three; but the greatest of these is love.” For now, American society appears to have fallen away from the values that really matter.

Using MLK

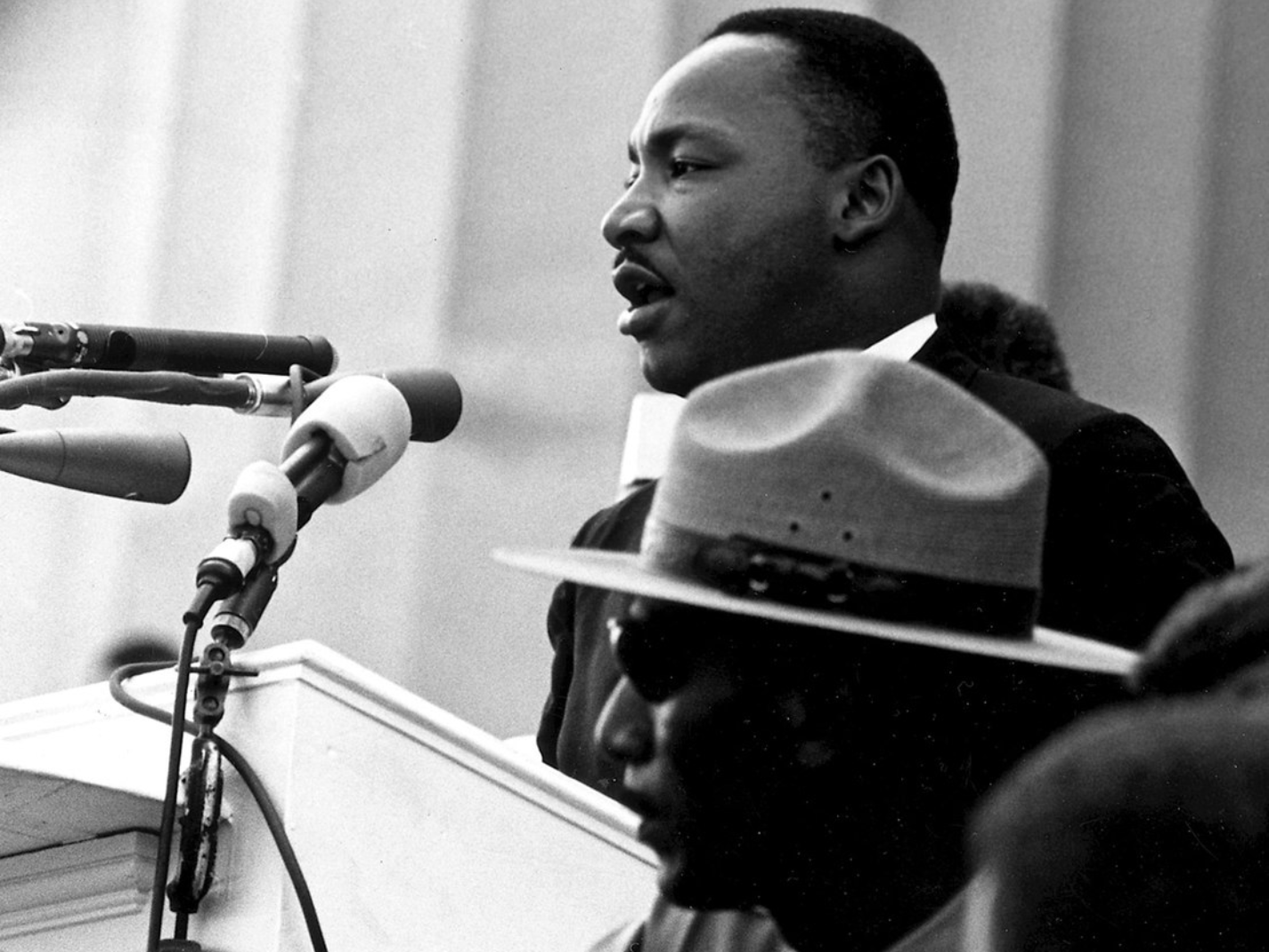

When it comes to the modern debate as to whether CRT belongs in schools, opponents of the theory are quick to invoke the name of Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s name is used in conjunction with several statements he made on character and colorblindness, with none more iconic than his I Have a Dream speech at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Critics are quick to point out that opponents of CRT should not use MLK’s name, or quote what he taught, and then go on to “ignore his real message.”

Those who use King for their argument of character over color would never quote what King wrote to his wife about his political views. One example, cited by Vox’s Fabiola Cineas, illustrates that King appears to have favored so-called “equity” in the realm of economics, writing that he was “much more socialistic” than capitalist.

[Related: “King, Kendi, and the Good People of Guilford, Connecticut”]

Others examples abound. Javonte Anderson of USA Today celebrates how “Martin Luther King Jr.’s words of unity and truth transcend how they are often twisted,” and Time published a piece titled “10 historians on what people still don’t know about Martin Luther King Jr.” Certainly, as with everyone who is larger than life, not all scholars agree on the meanings of King’s words.

There is a certain level of exhaustion developing over the argument as to whether King meant one thing or another. Wenyuan Wu, executive director of the Californians For Equal Rights Foundation, illustrates this exhaustion by referencing a query from antiracist Ibram X. Kendi, who asks, “Who has permission to quote MLK?” Wu then quotes Kendi, who asserts, “Those who distort King’s dream are now distorting critical race theory, and distorting CRT to distort King.”

During his heyday, writes Ijeoma Oluo, King was once labeled “the most dangerous man in America.” What was the danger? Was there fear of flipping the script and condoning violence against the dominant culture? This would please the modern neo-Marxists, who are trying to reinterpret King’s original messaging on character. The danger was that he would lead blacks, primarily in the South, to revolt and gain their rightful standing as citizens—this was a danger to the established hierarchy of the South. The lack of grace toward others was a catalyst of inequality and was evident in the dominant culture of the South. A lack of grace is again catalyzing America, but with a much different notion of equality.

King’s Letter from Birmingham jail was most eloquent and called out the white moderates who supported his message but disfavored his strategy in the South—even though it focused on nonviolent protests. It is true that King protested peacefully, “but he also pointed his finger at the white majority and asked them to take up the fight.” The fight for equality in the 1960s is quite different from the modern struggle for “equity,” which involves violently dismantling the system that preexisted King.

Would King support or discourage today’s fight, which cancels people, destroys their property, kills police, and seeks to overthrow American society instead of changing it? Would he have favored the 1960s version of CRT in his day? As a minister of the Gospel, could King have found a common cause with BLM, when it calls for the dissolution of traditional marriage and family and the diminishment of individuals? It would be nearly impossible to look back at the violence that emerged from the death of George Floyd and say that King would have supported the mayhem, murder, and destruction.

King lived through the deaths of President Kennedy (November 22, 1963) and Malcolm X (February 21, 1965). Only when King was assassinated on April 4, 1968 did cities experience major riots and destruction. The rhetoric used by Malcolm X in the 1960s could easily be heard from the lips of today’s neo-Marxist race-radicals.

King also understood that there was a time to pray and a time to act, echoing Solomon’s words from Ecclesiastes 3:1, “There is an appointed time for everything. And there is a time for every matter under heaven.” What’s more, King knew there would be accountability for the actions and inactions of mankind: “God will bring into judgment both the righteous and the wicked, for there will be a time for every activity, and a time to judge every deed.” (Ecclesiastes 3:17 NASB) Trusting in God’s grace is a better bargain than trusting in the plans of mankind.

King as Reclaimed Radical?

MLK is persona non grata in critical race theory and antiracism scholarship. Likewise, BLM is making every effort to reclaim King and portray him as a fellow radical leftist. As evidence, the Chicago branch of BLM was pushing the hashtag #ReclaimMLK on Twitter. The group asserts that turning the other cheek was too simplistic of a description of King’s radicalism, so it seeks to reinterpret King for the current generation and its push for equity.

It appears that character development and legislation that focuses on colorblindness is not enough for today’s activists. The neo-Marxism in their minds and hearts drives them toward revocation and removal of every mention of American character and any unifying values that connect to the past. Their efforts have their basis in the chant, no justice, no peace, and when it comes to killing law enforcement authorities, “filthy, disgusting animal” cops should “fry like bacon.”

[Related: “Critical Race Theory and Common Sense”]

Without peace there is violence and destruction—the likes of which MLK decried in his early years. It is true that some of King’s positions on race, racism, and peaceful protest were controversial for their time. LaNeysha Campbell, podcaster and entertainment writer, explains: “The reality is, what Dr. King believed in—non-violence peaceful protesting—was also considered to be radical at the time. I think some who post his quotes are sugarcoating and misrepresenting the true intention of Dr. King’s message to silence protesters who they deem are being ‘too radical.’”

There is some evidence to this effect, both in the attempts to enlarge the radicalism of King’s Gandhian approach to nonviolent protest and in the possible changes in his beliefs on the effects of violence near the end of his life. This is one reason BLM is seeking to transform the image of MLK. King is remembered largely as a civil rights icon, a man of faith, and a political leader of peaceful protest. People showed up to marches wearing their Sunday-best clothes and walked the streets. Azie Dungey, the creator of the web series Ask a Slave, elaborates:

In the ‘60s we wore our Sunday best, held hands, sang Christian songs, and did not fight back . . . because we were still proving we were as human as the white person . . . we should never have had to prove that. But that was the strategy.

Contrast the riots of more recent days. People today wear helmets, carry weapons, wear body armor, and lift signs with messages that would besmirch the legacy of King. Today’s rioters use Molotov cocktails and bring weapons. Who the media calls protesters, the rest of the nation calls revolutionaries.

King’s marches had character and honored the First Amendment. Today’s groups, such as BLM, harass people on the streets, walk into businesses, demonstrate anti-semitism, and assault those with whom they disagree. Of course, this does not pertain to all members of any one group. Yet, the strategy of overturning society is a joint goal.

If a group cannot practice nonviolent protests and yet claims the name of King, then there is only one option. There must be a concerted effort to remake King into someone as radical as they are. This is precisely what they are attempting to do. The modern neo-Marxist movement sullied King’s message of character some time ago. The current struggle against things like police brutality and law enforcement, in general, supplants the wider-reaching issues that are found in black families, the public schools in inner cities, and more.

The bottom line is summarized in five points: (1) There is no character in failing schools. (2) There is no character in poverty. (3) There is no character in dismantling the nuclear family. (4) There is also no character in law enforcement that treats people unjustly and unequally under the law. (5) There is no character in destroying that for which MLK was murdered. To develop true, lasting character, the American people must revisit the grace preached by Dr. King.

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from Dr. Zarra’s new book titled, From Character to Color: The Impact of Critical Race Theory on American Education (2022, Rowman & Littlefield).

I like to remind people that King was in Memphis to support a garbagemen’s strike — and that they were striking because two of their members had been crushed to death inside a defective truck. (This was before OSHA.)

King was defending individual rights.

Thanks for the comment, Ed. 🙂 Have a terrific weekend.

I’m sure we are all better off knowing that. Thanks for the reminder.