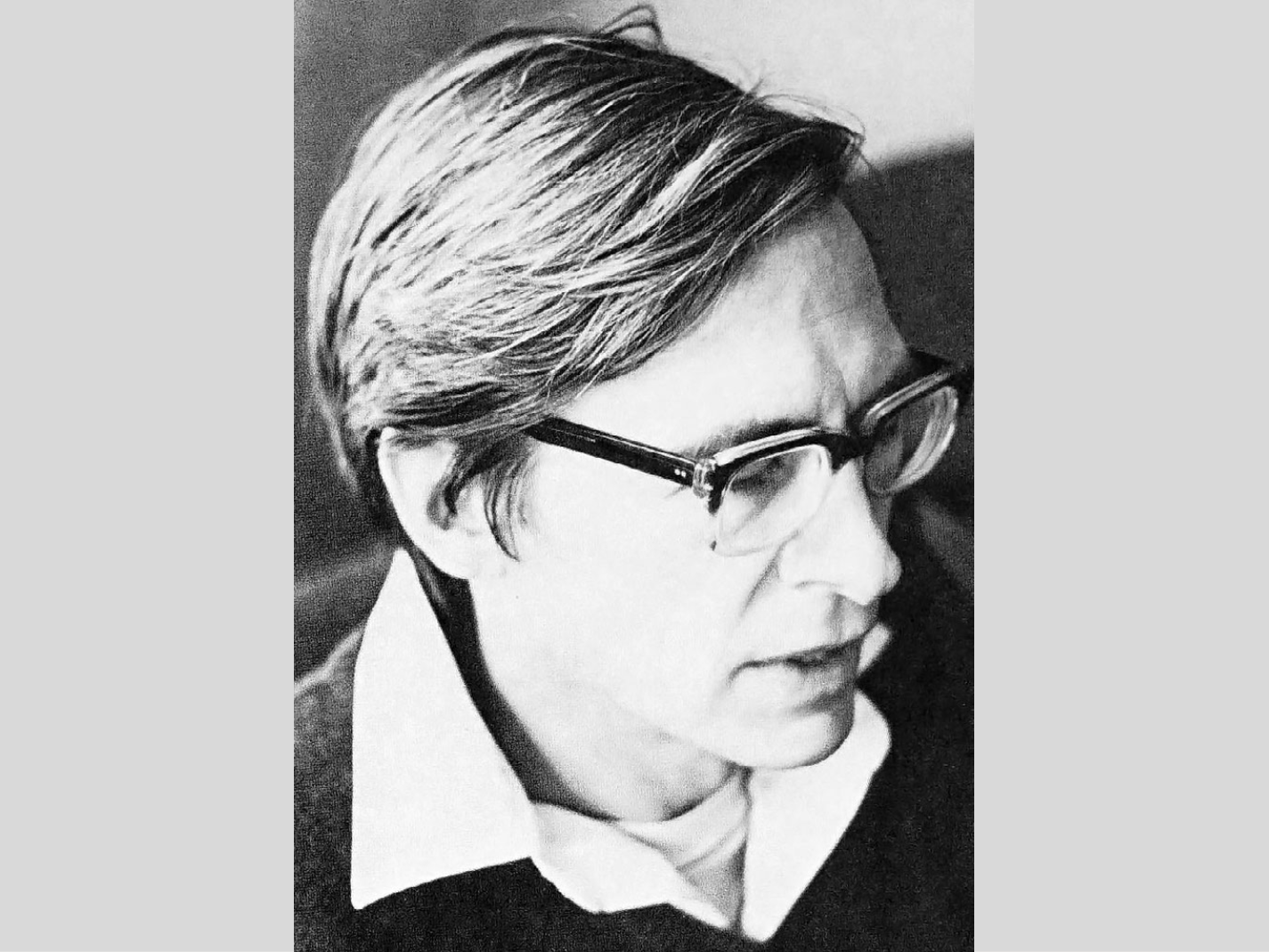

Fifty years ago, a little-known political philosopher at Harvard named John Rawls published a lengthy book titled A Theory of Justice at the well-cured age of 50. It was a bold offering because most people assumed that the major issues in political philosophy had been thrashed out by the greats. The only work remaining was to write learned commentaries on the canon and to investigate obscure alleyways.

Rawls saw that the Western canon of liberal political philosophy was under severe threat from the radicals of the 1960s. That tumultuous decade had produced a revival of Marxism among Western philosophers, alongside new radical philosophies like feminism, environmentalism, post-modernism, black chauvinism, and various cultish forms of anarchism. A Theory of Justice was a magnificently constructed and well-grounded reminder of why the Western liberal tradition was the most fair form of society, despite the critics. It did not challenge the liberal tradition but reinforced it with robust new foundations.

Merely describing the book in this way makes it clear that Rawls would be considered a conservative on campus today. As such, and despite his former reputation as a person of the Left, Rawls’s robust defense of a free society renders him more like a modern conservative. No one else has provided such an eloquent rebuttal to the assaults on freedom in the name of social justice and equity as he did. Conservatives should get over their suspicions about his redistributive beliefs and claim him for their own.

A fair society, Rawls argued, should be arranged along principles that everyone could accept no matter who or what they turned out to be. Such a society would make freedom its top priority, because no one would want to risk a situation where they were deprived of basic liberties in the name of someone else’s “social justice.” The philosopher Friedrich Hayek said he found nothing objectionable in Rawls because of this guarantee against Maos and Castros.

Rawls’s ideal society would also sanction wide inequalities as long as the absolute well-being of the worst-off members of society was as good as it could be: everyone could get on board with that, because if you turned out to be in that bottom group, things would work for your benefit. These arrangements depended critically on the fixity of borders and on membership in a political community, he argued, without which the basis for social cooperation would be broken. What was most important for everyone was to understand that it was society, not government, that held the keys to human flourishing.

Rawls had no truck with the idea of socialism or the welfare state. His ideal of a “property-owning democracy” became more important to his work in later years, where he recognized the stability provided by economic freedoms and competitive markets to both create and broadly distribute wealth. Political equality, not economic “equity,” was his guiding star. Left-wing critics now see him as part of conservatism’s stealth takeover of democracy because he provided a gentle, liberal-sounding spin to the market society and the minimal state.

Later, he added the idea of “public reason” as the basis on which political debates needed to take place. This required shared justifications and claims. No “culturally responsive” forms of democracy for him.

At the time of its publication, A Theory of Justice was seen as warmed-over socialism because of its insistence on a social principle to regulate inequalities and on rejecting entrenched social privilege. But today, the political debate has shifted. Most of the attacks on the book, as well as on Rawls’s subsequent work, come from the Left: too much scope for billionaires; no mention of race or gender; artificially limited to sovereign states with a liberal heritage rather than applied at the global level. And so on. At Harvard today, Rawls would be charged with “white supremacy” and sent for diversity training.

It is no overstatement to say that Rawls, who died in 2002, fully belongs in the pantheon of greats in modern political philosophy alongside Kant, Burke, Hayek, and Hume. His concept of “the original position,” in which people have to choose rules for society without knowing anything about themselves, has become a staple of modern political thought, in addition to inspiring many bawdy jokes. Americans do not seem aware that their country produced such a genius because his name remains little-known in the public.

But this is not just any great. This is a great of the classical liberal tradition, which is today part of modern conservatism. It’s not just that the political center has shifted Left, stranding Rawls on the conservative side of the spectrum—that is part of the story. The more compelling reason to consider Rawls a conservative is that his theory is based on freedom and individual responsibility first, and social justice second. It is a ringing endorsement of the status quo in contemporary liberal democracies. He is a conservative both in substance and in strategy. Conservatives should welcome him to their fold.

Curious argument.

The “Original Position” is a thought experiment that would commit conservatives to a program of global social intervention and uplift.

Original Position asks conservatives:

Would you really permit a system that condemns the majority of children at birth to a life of poverty if you knew that YOU could be reborn as one of those children?

Theory of Justice is a train wreck of a book.

John Rawls is not a conservative by any stretch of the imagination and should certainly not be “adopted” by conservatives. A conservative approach to order is entirely different from that of Rawls.

The author keeps using the term “modern conservative.” I am a PhD political theorist, and I have absolutely no idea what this term means. It’s certainly not in use among any political theorists I encounter.

It’s not that the academy has drifted left as much as it has become full-bore fascist, abandoning all presumptions of liberalism. Instead of merely professing others to be wrong and elaborating on the reasons why, the approach today is to simply silence and punish heretics.

Any presumption of academic freedom has long since been abandoned by a cadre of self-described “tenured radicals” who then hide behind false claims of “academic freedom” to avoid accountability for their abuses.

Sadly, I fear that academia as we know it is neither can survive, nor should — at least with the public largess of today.