I spent my early years believing in a euphonious lie that modern China was beautifully multicultural, with all its 56 ethnic groups living as one family in utter adoration of the motherland. This patriotic belief, consolidated through years of Marxist and Maoist training, was slightly shaken when I met my college best friend—a Yao minority who talks like me, enjoys the same cuisines, and celebrates the same cultural traditions as I do. Conformity in the name of social harmony and nationalist renaissance has hijacked the Chinese-style ethnic studies, appropriated by the Central Government. Celebration of China’s rich ethnic life is a symbolic joke of sanctified historical relics, inundated by top-down political indoctrination to obliterate any ethnic differences unless they provide photo ops for the annual galas. Opposing views to highlight different ways of life in ethnic communities are promptly canceled.

On the other hand, the experience I have had in America regarding ethnic studies has been the opposite, in that differences based on race and ethnicity are elevated as overarching factors of group identities, power, and privilege. But it is ironically similar to my experience in China because political indoctrination also plays an important role in streamlining American ethnic studies. The sweeping movement to institutionalize ethnic studies in California is a prime example of both racial tribalism and political indoctrination.

The current form of ethnic studies in California, the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum (ESMC), stokes racial divisions and animosity by subjugating our society to a binary, race-based lens and by perverting our nation’s complex history with a narrow framework of identity politics. Racial balkanization, the toxic practice of separating individuals into hostile racial boxes, has fueled this paradigm. Marxism is also referenced here, not to inspire collectivization of all ethnicities to serve “proletariat” governance, but to exaggerate disparities for a clear-cut, race-based “oppressor-victim” dichotomy.

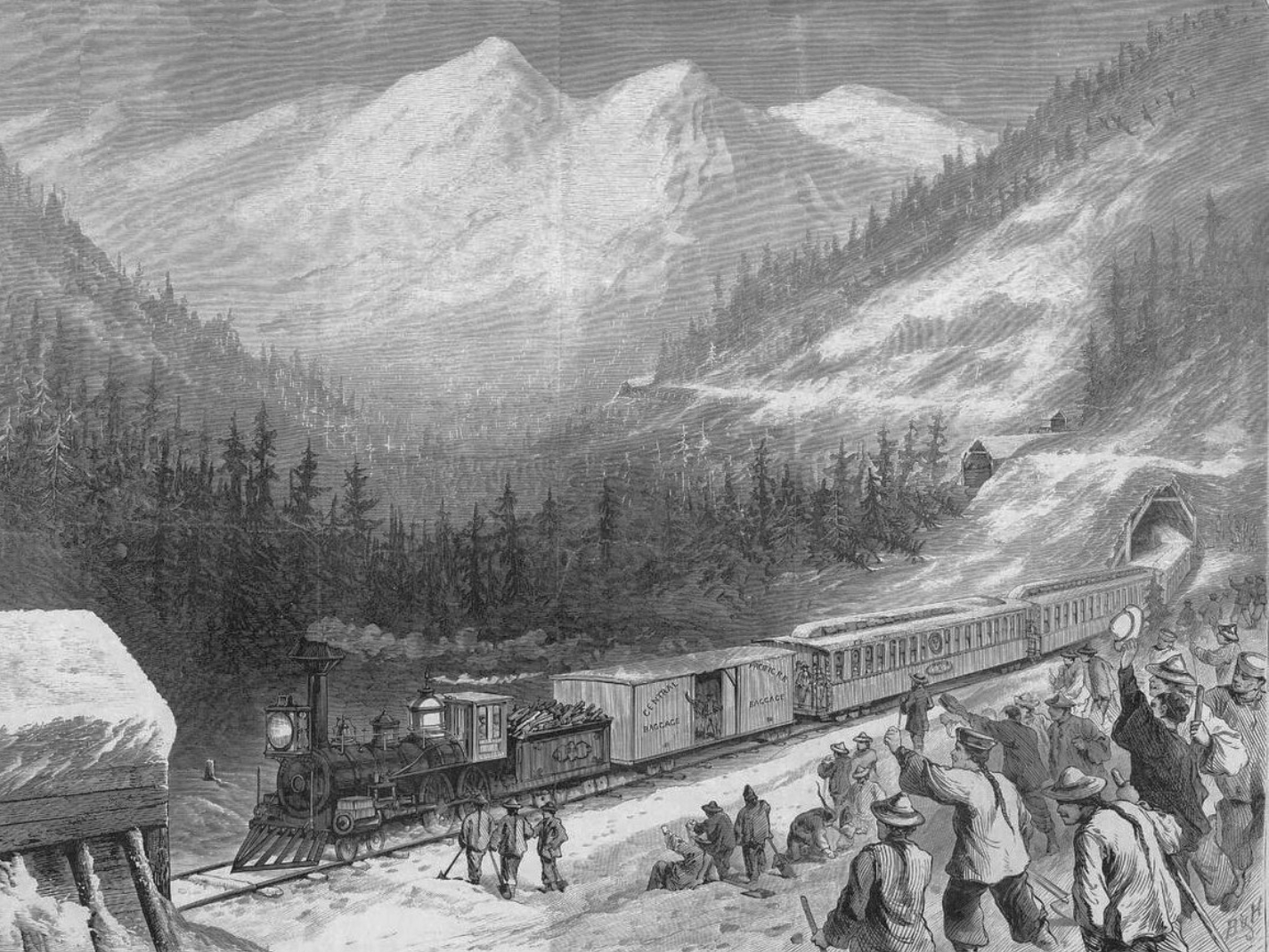

Perspectives on Asian-American history, for instance, reek of victimhood mentality and divisiveness. The ESMC sample lesson on “Chinese Railroad Workers” starts with a presupposition that Chinese laborers’ contributions to American infrastructure have been overlooked to “exemplify the white supremacy view of US history.” Then, it advises students to comprehend the construction and power interplay of the transcontinental railroads project through “systems of power” and “racism and exploitation.”

The curriculum even goes one step further, accusing the Golden Spike Foundation, a Utah-based organization that celebrates Chinese Americans’ contributions to the railroads, of not being representative of all Chinese railroad workers. To that point, the sample lesson zeros in on isolated incidents such as the 1867 Chinese railroad strike and the omission of Chinese workers in the image of the 1869 Promontory Point workers meeting. Curriculum authors criticize the foundation for not prominently highlighting the experience of Chinese strikers and labor organizers. In reality, the foundation has been advocating for a Utah curriculum that highlights stories of both Chinese and Native-American railroad workers. Golden Spike is instead being canceled for not engaging in victimization or promoting labor antagonism.

Admittedly, from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, to the Japanese-American internment during World War II, to xenophobic attacks against Korean Americans in the early 1990s, to current anti-Asian discrimination in educational access, Americans of Asian descent have endured historical marginalization and unfair treatment. However, rather than being defined by the past or our collective grievances, we choose to cherish our dynamic diversity, rich history, and important contributions to this nation. We want to be viewed as integral members of the American society, not as victims. True ethnic studies should reflect a holistic understanding of our proud cultural heritage and meaningfully address racism, bigotry, and misunderstanding by building bridges.

Generally speaking, California’s ethnic studies movement contains three prongs. Administratively, the State Board of Education is expected to finalize and publicize the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum by March 31, 2021. The current and third ESMC draft, slightly modified to include more perspectives and quash some anti-Semitic elements in previous drafts, still largely relies on a propagandistic framework. Legislatively, the California State Assembly is reconsidering a bill (AB101) to mandate ethnic studies as a high school graduation requirement, with its precedent (AB331) having been vetoed by the Governor just five months ago. In local districts, original authors and supporters of the more radical ESMC first draft have launched activist campaigns to lobby individual school boards to adopt the militant model curriculum through resolutions.

It is under this powerful network of support that ethnic studies courses throughout the state are becoming revolutionized to embrace a political agenda, under the pretense of advancing “racial justice” and combating omnipresent “systemic racism.” Third graders from an affluent minority community in Cupertino participated in a math class where they “deconstructed” their racial and social identities based on “power and privilege.” Public school teachers in San Diego were forced to take “white privilege” training sessions to acknowledge indigenous land rights and atone for the sin of “spiritually murdering black children.” R. Tolteka Cuauhtin, one of the original ESMC authors, led hundreds of high school students in Los Angeles to worship Hunab Ku, an Aztec God associated with human sacrifice, through a unity chant in an ethnic studies class. The San Mateo County Office of Education has partnered up with the Oregon Department of Education to offer workshops on “ethnomathematics” and thereby dismantle “white supremacy culture” in math education.

This movement took a bizarre twist when ethnic studies curriculum authors, including indigenous chant leader Tolteka Cuauhtin, threatened to remove their names from the ESMC because the latest version is not sufficiently radical or “liberated.” In response to a mounting grassroots opposition, proponents of critical ethnic studies have engaged in a smear campaign by calling the opposition “white supremacist, right wing, conservatives” and “bad faith actors.”

Contrary to such petulant accusations, two main groups of the opposition, namely Alliance for Constructive Ethnic Studies (ACES) and Educators for Excellence in Ethnic Studies (E4EES), are diverse grassroots coalitions of parents, educators, and concerned citizens from all racial, political, and professional backgrounds. These groups have shed light on important issues of divisiveness and indoctrination pertaining to ethnic studies through careful investigation and nuanced analysis. Rather than seeking dialogue with critics to improve the curriculum, the original authors of the ESMC use baseless demonization to dehumanize, minimize, and cancel opposing views.

As a new American, one of Asian descent, my willful participation in the counter-movement is rooted in a deep moral conviction of our human interconnectedness despite idiosyncratic differences. I believe in the type of ethnic studies that encourages individual empowerment, mutual respect, and historical nuances rather than the zero-sum racial tribalism being evangelized as the new social norm of public education. But apparently, according to the czars of California’s ethnic studies movement, I should be canceled for calling out ESMCS’s divisive and discriminatory nature.

I’m sorely tempted to point out here that those who do not know history may find themselves doomed to not only repeat the same historical screw-ups, but to improve upon the chaotic and inhumane results of their mistakes. For them, astonishingly, the world appears to have been born no more than a decade ago.

The determination to find new and improved ways to severely punish perceived enemies causes some people to collectively lose their humanity, apparently, which has no value whatsoever next to unassailable power. Most reasonable people (from upwards of a thousand or more ethnic backgrounds) would have good reason to not trust such agendas.

People whose ancestors came here from far away do bring useful and interesting insights. Instead of the same tired old “theories.”

America is full of millions of nonwhite citizens who don’t happen to be African American, who wish for real educations for their children. These are people who are not all on board with any concept of “supremacy” or “systemic” anything. They value education for its redeeming qualities, and aim to provide their children with all proper attitudes required for success in attaining an educated life.

Which is why so many of them succeed.

Curiously, no history of oppression (whatever it might be) thwarts them in their pursuit of that end. The reason for this is a great story in itself. Because, for some two centuries, it has been the story of America. And until the early 1960s, it was fast becoming the story of African America too.

Which begs a simple question: does real education exist for the purpose of turning up the hate thermometer? Or doing the opposite?

I am increasingly of the opinion that homeschooling is the only alternative to this insanity.

A good summation of the current climate when it comes to discussing ethnic studies.