This political season has been dizzying. The steep, plunging lows—the COVID mess and the urban riots—are such that they have left many of us queasy. Enough so, that in bleak moments a shadow of doubt passes through our minds: perhaps our governing system cannot bear the burdens we face and could come undone.

It is no coincidence that there has been an uptick in talk of a constitutional crisis recently. Usually, such talk hinges on some specific scenario: election results are close, votes are contested, and neither side concedes. What will the Supreme Court or the military do?

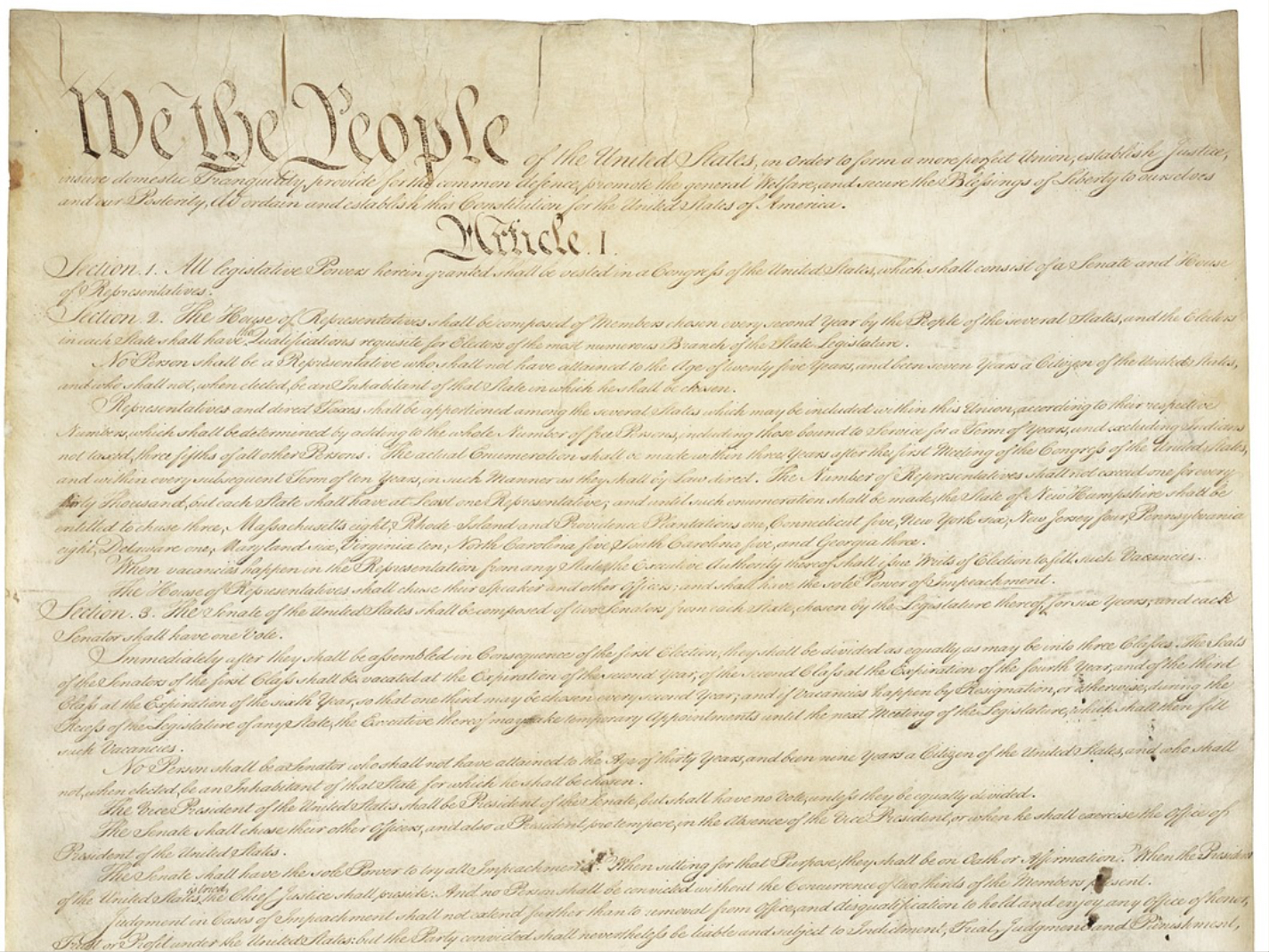

We’ll leave this and similar prospects to the war-gamers. There is, however, another form of constitutional crisis we should worry about, a quiet one that is already upon us. This is the crisis of our civic culture and the growing distance between the realities of our constitutional arrangements and the public’s understanding of them.

When thinking about government, for example, many people over-emphasize the notion that government exists to do the things we want it to do. Government solves problems, and we face serious ones. So it should take the lead in, for example, ending “systemic racism.”

Lost in this view is the understanding that our government, with its checks, balances, and various limitations, is not well-designed to enact ambitious policies, but was designed instead to protect liberties. With this in mind, former Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes once called the Constitution “the greatest instrument ever designed to prevent things from being done.”

Lost, too, is the understanding that the primary function of our constitutional system is to provide a forum in which the highly varied interests of the American people—the most diverse national population in human history—can be hashed out peacefully, yielding acceptable, if not lovable, policies.

This distance between public expectations of what the government can do and its profound constitutional limitations is part of what drives our current political distress. Facing the gap, there would seem to be two basic approaches toward bridging it. We might blame our constitutional system, especially for its inefficiency—some do today, calling for changes in the electoral college, the makeup of the Supreme Court, or of the Senate. (For a sample of this line of thought, see Farhad Manjoo’s New York Times op-ed from Oct. 14).

Or we might approach the matter from the other side and start with the citizenry rather than the Constitution. Consider the words of Walter Berns, channeling the Framers. Rather than insisting that “the Constitution be kept in tune with the times, the times, to the extent possible, must be kept in tune with the Constitution. Why, otherwise, have a constitution?”

In either case, whether we reform the Constitution or reform ourselves, we need to reconstruct our civic culture. The current misalignment is unsustainable.

One place to start in the repair work is to present anew the necessary building blocks: the words and terms we use whenever we talk politics. That is the goal of my new book, The Language of Liberty: A Citizen’s Vocabulary. In it, I define and explore 101 political terms, chosen to give readers a clear and comprehensive view of our political system by explaining it piece by piece. The terms range from down-to-earth and practical (caucus, statute, Senate) to the more philosophical (democracy, rights, liberalism, etc.). The noted historian Wilfred McClay says my book is “both a handy reference book and a work of philosophy, nicely parceled out into easily digested essays. I’ve never seen anything quite like it.” He also described the work as “splendid,” as well as “wise” and “subtle.”

The Language of Liberty: A Citizen’s Vocabulary is nonpartisan, ideologically even-handed, and aimed at a general audience. We face real civic challenges, and our political future depends on the decisions we make today. Clarity is in order. I hope to have provided some with my book.

The Language of Liberty: A Citizen’s Vocabulary (Rootstock Publications, 2020) is available now from Amazon, Alibris, and other providers.

Image: WikiImages, Public Domain