At the American Historical Association’s recent annual meeting, the program’s abundance of panels were devoted to issues of social justice. Perhaps its name should be changed to the Activists Historical Association.

Here are a few examples:

- Historically Informed Present-Day Activism in the City

- Activism, Academics, and the Academy

- African Americans and Chinese Activists in World War II and the Cold War

- Organizing K–12 Teachers, Academics, Students, and Activists

- Educating for Activism? Historians and Politics in the Contemporary United States

- The Unexpected Activists: AIDS Activism beyond New York City and San Francisco

- Female Killers in the 20th Century: Gender, Modernity, and Punishment in Comparative Perspective

- The Nazi Legacy in the Trump Era: Research, Pedagogy, and Public Engagement

- Gendered Mobilities and Colonial Intimacies: Histories of Migration and Settlement in the Age of Empire

- Mass Protests in Historical Perspective—Hong Kong, Ecuador, Lebanon, Chile

- Shut Up and Play: Sport, Labor, and Activism in the Global Sports Industries

- The Gender of Power

- Catholic Action and Political Activism in Uganda and the United States

- Gender and Leadership: Matrilineages, Struggle, Liberation, and Feminist Approaches

- Unhappy Women: Emotions and Gender Politics in Modern Italy

- The Native Pathways of Colonial Contacts: Kinship, Alliances, and Gender in the Early Modern Americas

- Historians and Presidential Misconduct

- Writing the History of American Conservatism in the Era of Donald Trump

“Are the hatreds now being so nakedly expressed toward immigrants and minorities typical of the new conservatism or of the old conservatism—or not typical at all? Has Trump opened historians’ eyes to the central place that racism has always played in postwar conservatism?”

When not attending a panel on one or another kind of activism, historians could take “a tour of LGBTQ Materials at the Schomberg Center,” attend an open forum committee meeting on “LGBTQ Status in the Profession” and the “LGBTQ Historians’ Reception,” and perhaps enjoy some scrambled eggs at the “Breakfast Meeting of the AHA Committee on Gender Equity.”

“At this year’s gathering,” Inside Higher Ed reported, “there was a sense that historians’ perspectives are sorely needed in current policy discussions — and that historians are increasingly willing to step up.” According to Janet Ward, professor of German history at the University of Oklahoma and chair of the panel on the Nazi legacy in the Trump era, historians “have to move beyond what we were trained to do” and “be braver.” Activism, she stated, “isn’t necessarily a bad word.”

Aside from the question of how much bravery is required to support gender equity or oppose Trump on today’s campuses, for a good while now, historians have been more than “willing to step up.” Indeed, it is impossible to find any hot button, controversial issue over the past twenty years or more that did not attract the active participation of historians, invariably supporting the progressive side on every issue.

As I wrote here, when the public encounters historians these days, it is all too often in the form of politically correct scolds — in Op-Eds, petitions, legal briefs — offering their scholarship (and all too often only their political opinions) as ammunition to progressives in various cultural skirmishes.

A few examples: in the recent past, historians, sometimes hundreds of them, have signed legal briefs supporting abortion rights, supporting gun control, opposing laws prohibiting homosexual sex, supporting gay marriage, arguing that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 allows claims for retaliation, prohibits discrimination by private parties as well as government, and, perhaps most remarkably, even arguing that the 14th Amendment bars state constitutional amendments that require colorblind equal treatment.

In addition to filing legal briefs and serving as expert witnesses in politically charged litigation, historians have also circulated innumerable petitions and passed resolutions at their professional meetings, always taking the progressive side in political controversies. One opposed the legal views of a Bush administration official; another opposed the nomination of a federal judge. And then there are the petitions and letters to editors and Congress, often with a cast of hundreds or thousands, such as this one, signed by over 2200 ostensible historians opposing the war in Iraq.

These examples of what can be called pontificating public history have several things in common. One is the striking absence of nuance, of humility, of any hint of suspicion that informed and reasonable people could disagree. A classic example is Princeton historian Sean Wilentz’s Congressional testimony opposing the impeachment of President Clinton.

Wilentz had organized a letter to The New York Times (quoted here) opposing Clinton’s impeachment signed by over 400 historians, including such prominent scholars as C. Vann Woodward and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Writing “as historians as well as citizens,” the worthy signers argued that the charges against President Clinton did not rise to the level demanded by James Madison for impeachment. They charged that “the vote of the House of Representatives to conduct an open-ended inquiry creates a novel, all-purpose search for any offense by which to remove a President from office.” This new theory of impeachment, they continued, “is unprecedented in our history” [something that can no longer be said], and unless abandoned will leave the Presidency permanently disfigured and diminished.”

In his 8 December 1998 testimony, Wilentz stated in what even the Times characterized as a “gratuitously patronizing presentation,” that

each of you on the committee and your fellow members of the House must decide, each for him or herself, is whether the actual facts alleged against the president, the actual facts and not the sonorous formal charges, truly rise to the level of impeachable offenses.

If you believe they do rise to that level, you will vote for impeachment and take your risks at going down in history with the zealots and the fanatics.

If you understand that the charges do not rise to the level of impeachment, or if you are at all unsure, and yet you vote in favor of impeachment anyway for some other reason, history will track you down and condemn you for your cravenness.

Rep. William Jenkins (R. Tenn) stated, “We need to remember that what you came armed with is a bunch of opinions. And like they say back in Tennessee, everybody’s got those.”

Wilentz replied, “There’s a difference between opinion and scholarship. Anybody can have an opinion. What I reported here has to do with scholarship.”

Wilentz Redux

Now, Princeton’s peripatetic petition promoter is back, having just before the recent AHA convention organized a statement signed, as of this writing, by over 2000 historians supporting the impeachment of President Trump.

These historians remind me of James Silver, the University of Mississippi historian and author of Mississippi: The Closed Society, who stated in a lecture at Stanford that I attended in 1965 that Mississippi is the only state in the union that had remained a one-party state while changing parties. In a similar fashion, Wilentz and his current cohort are as certain as he and his 1998 cohort were that they and they alone have a direct line to James Madison, whom they have no doubt whatsoever would support the impeachment of Trump as certainly as he would have opposed impeaching Clinton. “President Trump’s numerous and flagrant abuses of power, “they assert with Ph.D-degreed confidence, “are precisely what the Framers had in mind as grounds for impeaching and removing a president.”

Precisely? No Doubt

As Andrew Ferguson pointed out incisively in The Atlantic, “no one knows precisely what the Framers had in mind.” But “precision,” he continues, “is precisely what the historians are not after.” What they offer instead “is a reflexive form of what logic-choppers call an argumentum ab auctoritate, or argument from authority. The idea is to prove a disputed claim by pointing out that some expert or other authority believes the claim to be true. It’s a bogus but very popular trick.”

Just as the effort to impeach Donald Trump began even before he was inaugurated, as the Washington Post pointed out on January 20, 2017, large numbers of petition and statement-signing historians did not wait until the last minute to share their wisdom about what Americans should learn from “the lessons of history” they were presumably vouchsafed to teach.

In a July 2016 Open Letter to the American People, over 600 historians organized as Historians Against Trump wrote that “As historians, we recognize both the ominous precedents for Donald J. Trump’s candidacy and the exceptional challenge it poses to civil society…. The lessons of history compel us to speak out against a movement rooted in fear and authoritarianism. The lessons of history compel us to speak out against Trump.” After Trump was elected — that is, after voters proved they were not “resistant to cynical manipulators who sell snake oil as historical truth” — over 1200 historians signed a statement “urg[ing] Americans to be vigilant against a mass violation of civil rights and liberties.”

All public pontifications from historians are based on this argument from authority, but they also share one other common feature: much of the claimed authority is unearned. The December 2019 statement calling for President Trump’s impeachment, for example, begins by stating, “We are American historians devoted to studying our nation’s past who have concluded that Donald J. Trump has violated his oath to “faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States” and to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Many of them, however, are not American historians, or even historians at all.

I did not examine all 2019 signatories to the Wilentz II statement favoring impeachment, but here are just a few identifications and representative publications provided by signatories that I found by quickly skimming some of those whose last name begins with “S”:

- A historian of science, especially chemistry

- A professor of creative writing

- A specialist in Latin America

- A professor of classics, but also “the music and poetry of Bob Dylan”

- An anthropologist specializing in Latin America

- A professor of “Peace and Global Studies”

- “The Unique Decline of Mortality in Revolutionary France”

- Monsters of the Gevaudan

- “Will The Real Mango Please Stand Up? Defending Dharma and Historicizing Hinduism”

Equally underserving of the special authority they claim are the large numbers of signers who may be American historians but whose specialties or representative publications give them no special expertise in Constitutional matters. A few examples — there are tons more — also just from the “S” surnames:

- Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit

- Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York

- The Vegetarian Crusade

- The Newark Earthworks

- US Foreign Policy and Muslim Women’s Human Rights

- Signifying Female Adolescence

- Envisioning Women in World History

- Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America

In fact, there are exceedingly few signatories whose scholarship should award them any special deference in matters involving Madisonian mind-reading, and this absence of any earned authority on the part of most signatories is shared by all the historian petitions and public statements I’ve seen.

As I noted here, for example, in discussing the lack of qualifications by nearly all of these historians to pronounce from on high about the evils of President Bush’s Iraq policy, most had no claim to professional expertise on what the Constitution requires in the making of war. (Examples: environmental history in colonial America; the history of sexuality; how Jewish women shaped modern America; social history adolescent boys and violence; etc.) As citizens, they had every right to express their opinions, but they did not offer their opinions as citizens but as “the undersigned American historians.”

Politics, Not “Presentism”

In writing about the AHA convention, Inside Higher Ed discussed what it called “the presentism trap.” Historians, it claimed, “are, by training, often hesitant to analyze current events through that lens, lest they fall into the ‘presentism’ trap of interpreting the past anachronistically…. But many historians are feeling less inhibited about sharing their perspectives on what’s happening right now.”

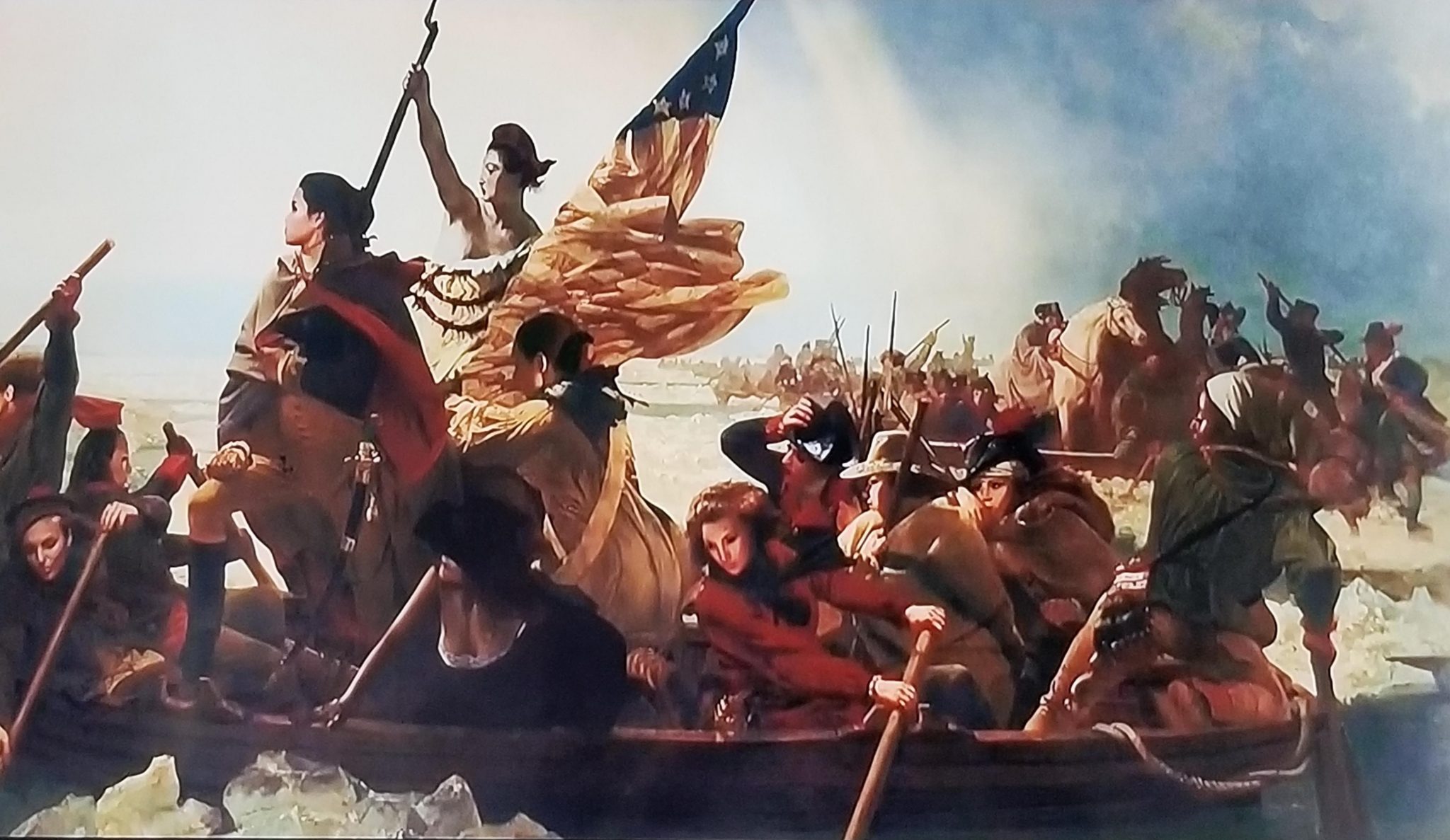

This is exactly backward. “Presentism” is explaining and judging the past from the vantage point of — and using the values and standards of — the present. It is “presentist,” for example, to criticize George Washington for not being an environmentalist when he chopped down the cherry tree, or to blame Thomas Jefferson for not being a Marxist.

When historians are busy “sharing their perspectives on what’s happening right now,” as they increasingly are, they are not presentists but progressives, active ideological and partisan combatants in our political and cultural wars.

The fact that the contributions of historians to public discourse and debate are skewed heavily to the left is hardly surprising since the entire American historical profession is skewed heavily to the left. A recent study of the ratio of Democratic to Republican voter registration in five fields found the following: Economics, 4.5:1; Law, 8.6:1; Psychology, 17.4:1; Journalism/Communications, 20.0:1; History, 33.5:1.

Table 3 of that study provides the party registration ratios by university and department, and some of the better-known history departments have quite dramatic imbalances: UCLA, 67:1; Columbia, 63:1; NYU, 44:1; Duke, 42:1; Princeton: 36:1; Stanford: 33:1; Harvard: 26:1. On the other end of the scale, Caltech at 8.0:1 was less unbalanced than MIT at 9:0:1 by one point.

Perhaps U.S. News & World Report can combine this data with the institutional affiliations listed on the various polemical petitions by historians to rate history departments by their wokeness. By the same token, prospective students attempting (apparently with little hope of success) to avoid extreme ideological imbalance could use such a wokeness index to learn where not to apply.

In what is either irony or poetic justice, the more historians pontificate in public the less respect they and their profession receive. The monotony of their “history lessons” seeming always to endorse progressive positions has led to warnings that they risk being regarded as just another liberal interest group.

“By signing letters about the constitutional standards governing impeachment, an issue most of them know very little about, many academics placed partisanship and self-interest above all else,” William and Mary law professor Neal Devins warned in a powerful article. “When academics join forces to send a purely political message, their reputation as truth-seekers will diminish and, with it, their credibility.”

Stanley Fish made similar points in a stinging New York Times OpEd. “The profession of history shouldn’t be making political pronouncements of any kind,” he wrote. “Were an academic organization to declare a political position, it would at that moment cease to be an academic organization and would have turned itself — as the Historians Against Trump turn themselves — into a political organization whose arguments must make their way without the supposed endorsement and enhancement of an academic pedigree.”

Historians who sign partisan petitions, Fish concluded, “invest their remarks with the authority of their academic credentials, and by doing so compromise those credentials to the point of no longer having a legitimate title to them,” at least when they write and publish their polemics.

Silence…

Perhaps the clearest evidence that historians’ contributions to public discourse are unfailingly progressive is those controversies where they choose not to comment at all.

Hillary’s Email

Take Hillary’s purloined and destroyed public records, “her” email. The historical profession, acting through its associations (American Historical Association, Organization of American Historians, Society for the History of American Foreign Relations, etc.) and their various committees, has a long and honorable history of zealously promoting and protecting the preservation of and access to government information through litigation and other forms of public pressure.

Yet throughout the controversy over Hillary’s email, historians stood or sat, mute. I discussed that history and that silence in “Hillary’s Emails: The Silence of the Historians,” but I neglected to mention one notable. episode. In January 2007, the business meeting of the American Historical Association passed “an unprecedented resolution” condemning “United States Government Practices Inimical to the Values of the Historical Profession.” Prominent among those heinous practices was “reclassifying previously unclassified government documents,” which violated the AHA’s “principles of free speech, open debate of foreign policy, and open access to government records in furthering the work of the historical profession.”

But regarding Hillary’s massive destruction of mounds of public records documenting her tenure as Secretary of State, not a peep from the historians. Perhaps I could be persuaded that our public access watchdogs would also have refused to bark if the arsonist of this bonfire of the documents had been a Republican, but I doubt it.

The New York Times 1619 Project

It’s not as though there has been no criticism from historians of the shoddy, offensive attempt of The New York Times to (is “blackwash” the opposite of “whitewash”?), well, present all of American history as nothing more than one example of racism after another. Indeed, Princeton’s seemingly permanent resident of the public square, Sean Wilentz, has spoken and written against it and applied his indefatigable organizing talents to securing a letter to the New York Times.

But wait. That letter was signed by, in addition to Wilentz himself, only four other historians (all of them distinguished). Where were the hundreds, thousands, of signatures that appear on most missives from historians about grave matters of public policy? “Wilentz reached out to a larger group of historians, but ultimately sent a letter signed by five historians who had publicly criticized the 1619 Project,” Adam Serwer wrote recently in The Atlantic.” He told Serwer that the idea of trying to rally a larger group was “misconceived.”

If so, perhaps he discovered that many historians did or would refuse to sign because, according to Serwer, they “wondered whether the letter was intended less to resolve factual disputes than to discredit laymen who had challenged an interpretation of American national identity that is cherished by liberals and conservatives alike.” As Nell Irvin Painter of Princeton explained why she refused to sign,

I felt that if I signed on to that, I would be signing on to the white guy’s attack of something that has given a lot of black journalists and writers a chance to speak up in a really big way. So, I support the 1619 Project as kind of a cultural event. For Sean and his colleagues, true history is how they would write it. And I feel like he was asking me to choose sides, and my side is 1619’s side, not his side, in a world in which there are only those two sides.

Given the influence of the Times, it is odd that far fewer historians felt the need to make their views known about the 1619 Project’s warped recommended school curriculum than, say, about changes in a Texas schoolbook.

… And Silencing

The ideological conformity of historians has not served either the public or themselves well. Public discourse with only left voices being heard has the resonance of one hand clapping.

No doubt part of the explanation of the absence of conservative petitions etc. is, as we have seen, there aren’t many conservative historians. But there are some, and there would probably be more if they did not have a reasonable fear that coming out of the closet and going public would subject them to professional retribution, harassment, shunning, and worse.

That fear is reasonable, as revealed by the involvement of one of the supporters of public engagement at the recent AHA convention quoted by Inside Higher Ed, Professor Emerita Sandi Cooper of the College of Staten Island, in a furious controversy over a historian’s testimony as an expert witness in EEOC v. Sears, Roebuck and Company, 628 F. Supp. 1264 (1986), 839 F.2d 302 (1988), that ran afoul of the feminist party line. [I “practiced history” with the small law firm that represented Sears, and discussed the controversy among historians about it here.]

An untenured assistant professor of history at Barnard College had testified, in EEOC v. Sears, Roebuck and Company, 628 F. Supp. 1264 (1986), 839 F.2d 302 (1988), that women’s career choices were heavily influenced by contemporary sex roles and that an employer could not be held responsible for a labor force in which more men than women were qualified for, interested in, and available for such jobs as installing home heating and cooling systems.

For this heresy, The New York Times reported, she was attacked on “panels at scholarly conventions, articles in educational, historical and feminist publications and in often vituperative private dialog.” The Nation argued that historians should testify in sex discrimination cases only if doing so “helps working women” and that her argument “plays into the hands of conservatives.” The Coordinating Committee of Women in the Historical Profession passed a resolution at the American Historical Association convention declaring that “We believe as feminist scholars we have a responsibility not to allow our scholarship to be used against the interests of women struggling for equity in our society.”

The Times article quoted the chairman of that committee, “Professor Sandi E. Cooper of the College of Staten Island,” who called the offensive public testimony “an immoral act.”

Roger Baldwin of the American Civil Liberties Union used to criticize those who believe in “civil liberties for our side only.” I suspect that the recent enthusiasm for activist historians is limited to activists for progressive causes only.

As an historian in the obsolete sense of the term, I am deeply impressed by, and profoundly grateful for, Mr Rosenberg’s brilliant essay: and horrified by the circumstances about which he writes. As a conservative, I continue to hope that before long President Trump will turn his big guns on the horrifying corruption of American colleges and universities by liberal zealots.Those institutions have become the breeding ground of the Swamp,and pose great dangers for the future of our country.

But look at all the History majors they are attracting!