The New York Times recently drew a lot of attention for its “1619 Project” initiative, which has been criticized for misrepresenting the role of the slave trade as the central core to the development of the United States. The Times “aims to reframe the country’s history, understanding 1619 as our true founding, and placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are.

The project name purportedly refers to the date the first African slaves were brought to the English colonies that later became the United States. Like much else in the Times’ version of the role of slavery in American history, even the project name is rooted in distortion. Although the institution of slavery is a stain on national history, the true story is much more complex than the Times represents, and the United States plays a role both as a country that exploited the slave trade as well as a leader in the movement to end the African slave trade, and was not the primary instigator or beneficiary of the brutal trade.

1619 was not, in fact, the date of the first African slaves in the English colonies — those Africans were brought in under indenturement contracts, not bought as slaves. They were contracted to a fixed period of labor (typically five years) to pay for the cost charged by the Dutch slavers, at which point they were freed with a payment of a start-up endowment.

Indenturement Contracts, Not Slaves

This was not unusual or limited to Africans – approximately half of the 500,000 European immigrants to the thirteen colonies prior to 1775 paid for their passage with indenturement contracts. Anthony Johnson, a black Angolan, was typical – he entered Virginia as an indentured servant in 1621, became a free man after the term of his contract, acquired land, and became among the first actual slaveholders in the colonies.

[The New York Times Rewrites American History]

The first actual African slave in the colonies was John Punch, an indentured servant sentenced to slavery in 1640 in Virginia by the General Court of the Governor’s Council for having violated his indenturement contract by fleeing to Maryland. In 1641, the Massachusetts Assembly passed the first statutory law allowing slavery of those who were prisoners of war, sold themselves into slavery, or were sentenced to slavery by the courts, but banning it under other circumstances.

Early slavery, like indenturement contracts, was not specifically targeted at those of African descent. The Massachusetts law was primarily intended to allow slavery of captured Indians in the aftermath of King Phillip’s War. The 1705 Virginia Slave Codes, for example, declared as slaves those purchased from abroad who were not Christian. A Christian African entering the colony, for example, would not be a slave — but a captured American Indian who was not a Christian would be.

Black vs. Black

Ironically, a freed black man initiated the court case that moved slavery to a race-based institution. The Angolan immigrant Anthony Johnson was the plaintiff is a key civil case, where the Northampton Court in 1654 declared after the expiration of the indenturement contract of his African servant John Casor that Johnson owned Casor “for life,” nullifying the protections of the contract for the servant and essentially establishing the civil precedent for the enslavement of all African indentured servants by declaring that a contract for such servants extended for life, rather than the fixed term in the contract.

It was not until 1662 that the children of such slaves became legally slaves rather than free men, in a law passed in Virginia. The African slave trade itself was minor until King Charles II established the Royal African Company with a monopoly on the slave trade to the colonies. As late as 1735, the Colony of Georgia passed a law outlawing slavery, which was repealed due to a labor shortage in 1750. The boom in the import of slaves actually began around 1725, with half of all imported slaves arriving between then and the onset of the American Revolution in 1775.

Relatively speaking, the United States was a minor player in the African Slave Trade — only about 5% of the Africans imported to the New World came to the United States. Of the 10.7 million Africans who survived the ocean voyage, a mere 388,000 were shipped directly to North America. The largest recipients of imported African slaves were Brazil, Cuba. Jamaica, and the other Caribbean colonies. The lifespan of those brought into what is now the United States vastly exceeded those of the other 95%, and the United States was the only purchaser of African slaves where the population grew naturally in slavery – the death rate among the rest was higher than the birth rate.

While the institution, even in the United States was a brutal violation of basic human rights, it tended on average to be far more humane than in the rest of the New World.

The World Slave Trade

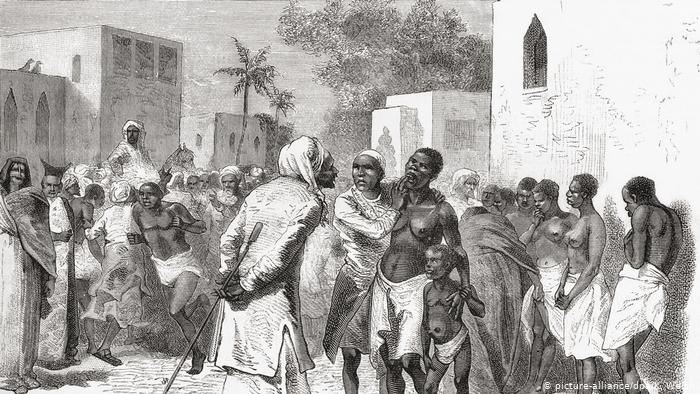

The Trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean African slave trade, which began by Arabs as early as the 8th Century AD, dwarfed the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and continued up to the 20th Century. Between the start of the Atlantic Slave Trade and 1900, it is estimated that the eastern-bound Arab slave traders sold over 17 million Africans into slavery in the Middle East and India, compared to about 12 million to the new world – and the Eastern-bound slave trade had been ongoing for at least 600 years at the START of that period.

The Western-bound Atlantic slave trade, contrary to the misrepresentation in “Roots,” did not involve the capture of free Africans by Europeans or Arabs, but by the trading of slaves (already a basis for the economy of the local animist or Muslim kingdoms) captured in local wars to Western merchants in exchange for Western goods. The first such slaves brought to the Western Hemisphere were brought by the Spanish to their colonies in Cuba and Hispaniola in 1501, almost a century and a half before the first slave in the English colonies that became the United States.

The last African state to outlaw slavery, Mauritania, did not do so until 2007, and if the institution is illegal on the continent de jure, it still is widespread de facto in Mauritania, Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan, as well as parts of Ghana, Benin, Togo Gabon, Angola, South Africa, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, Libya, and Nigeria.

The contradictions slavery posed on the rebel colonies during the Revolution sparked a backlash against slavery and the slave trade. Colonel John Laurens, son of a large South Carolina slaveholder, noted the contradictions in 1776, stating that “I think we Americans at least in the Southern Colonies, cannot contend with a good Grace, for Liberty, until we shall have enfranchised our Slaves. How can we whose Jealousy has been alarm’d more at the Name of Oppression sometimes than at the Reality, reconcile to our spirited Assertions of the Rights of Mankind, the galling abject Slavery of our negroes. . . . If as some pretend, but I am persuaded more thro’ interest, than from Conviction, the Culture of the Ground with us cannot be carried on without African Slaves, Let us fly it as a hateful Country, and say ubi Libertas ibi Patria.”

The US Constitution Leads the World in Banning the Slave Trade

More shared that sentiment, and the first law in the European world to ban the slave trade was, in fact, the US Constitution, which in 1787 included language allowing the slave trade to be outlawed as of 1808 with the understanding that Congress would act on it at that time. In Massachusetts, a 1783 court decision ended slavery, and all of the Northern States had passed emancipations laws by 1803. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 outlawed slavery in territories north of the Ohio River. Other countries followed suit. Denmark-Norway banned the slave trade in 1803, but not slavery until 1848. Britain passed a law abolishing the slave trade in 1807, and enforced it with the Royal Navy, and abolished slavery itself in 1833.

In 1807, Congress passed legislation making the import of slaves to the United States a federal crime, and in 1820, Congress passed the Law on Slave Trade, which went beyond the British law in declaring slavers as pirates, punishable by death instead of mere fines – and the US Navy joined the Royal Navy in active interdiction of slave ships.

Economically, the institution of slavery, rather than develop the economy of the new nation, stunted its development. Although bonded labor, whether slave or indentured servant, clearly played an important role in developing a labor force in the early colonial days, its role in the advancement of the economy in the newly established country is questionable. Gavin Wright, in his classic book The Political Economy of the Cotton South, shows in fact that slavery hindered the development of the economy in those states where it remained legal. The artisans, tradesmen, and unskilled labor pool necessary for developing a thriving, diverse economy were discouraged by competition from bonded labor, and the slave-owning class showed little interest in such an economy.

How Slavery Stalled the Economy of the New Country

Increasingly, the economy came to be dominated by cotton monoculture, boosted by the invention of the cotton gin, and the value of the capital invested in slaves. In order to maintain the value of this capital investment, demand for slave labor needed to be maintained, which led to the slaveholding states demanding the opening of new lands for slave cultivation. Wright shows that, contrary to the assertions of many modern critics who try to claim that slavery was responsible for the development of the US economy and to the mistaken belief of secessionists prior to the Civil War, cotton was not King, but rather the greatest return from slaveholding was the capital increase from the reproduction of slaves.

Without new lands to be worked by the expanding slave population, the price of slaves would fall, and the wealth of the ruling classes in the Southern states would have plummeted. Thus, issues like the Wilmot Proviso or Kansas-Nebraska Act, which threatened to close off the expansion of lands to be worked by slaves, posed an existential threat to the wealth of the slaveholders. Meanwhile, unencumbered by the institution of slavery, those states that abolished the institution and emancipated existing slaves embraced other forms of generating wealth, including a manufacturing economy that rapidly outpaced that of the slave states. The Civil War was, in large part, won because of the economy of free labor produced at rates that the economy of slave labor could not imagine. In fact, it was not until the abolishment of the Jim Crow laws preserving vestiges of the slave system that the economy of the New South truly began to take off.

While undoubtedly the issue of slavery and conflicts over its contradiction with the ideals of the new Republic shaped the political debates of the new country through the Civil War, it is going too far to assert that the slave trade and slavery were the central core of the development of the United States. Rather, it is more true to state that the ideals of the Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment and political beliefs shaped by the English Civil War and Glorious Revolution created an environment that exposed the immorality of slavery and established the political grounds for ending the slave trade, and eventually the institution of slavery in areas of Western European influence.

It was not a simple process, and required painful conflict to negotiate the conflicts and contradictions between the liberal ideal and the self-interest of those who owned human chattel, but ultimately rather than allow slavery to drive the growth of the nation, the new United States became a leader, along with their cousins in the Anglosphere, in the efforts to end the brutal and illiberal practice of slavery.

The New York Times does a disservice to its readers with the 1619 Project by presenting a simplistic and misleading story of the complex role that the institution of slavery played in the history of the United States, and it largely ignores the role that the underlying values of the Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment that undergird the new nation played in ending slavery and the slave trade.

(This article was updated on October 10, 2019.)

I don’t think those first Africans in Virginia themselves “signed off on indenturement contracts”. Read this:

The Africans who came to Virginia in 1619 had been taken from Angola in West Central Africa. They were captured in a series of wars that was part of much broader Portuguese hostilities against the Kongo and Ndongo kingdoms, and other states. These captives were then forced to march 100-200 miles to the coast to the major slave-trade port of Luanda. They were put on board the San Juan Bautista, which carried 350 captives bound for Vera Cruz, on the coast of Mexico, in the summer of 1619.

Nearing her destination, the slave ship was attacked by two English privateers, the White Lion and the Treasurer, in the Gulf of Mexico and robbed of 50-60 Africans. The two privateers then sailed to Virginia where the White Lion arrived at Point Comfort, or present-day Hampton, Virginia, toward the end of August. John Rolfe, a prominent planter and merchant (and formerly the husband of Pocahontas), reported that “20. and odd Negroes” were “bought for victuals,” (italics added). The majority of the Angolans were acquired by wealthy and well-connected English planters including Governor Sir George Yeardley and the cape, or head, merchant, Abraham Piersey. The Africans were sold into bondage despite Virginia having no clear-cut laws sanctioning slavery.

https://historicjamestowne.org/history/the-first-africans/

I just want to make this point, John Punch was not the First Slave in the 13 colonies. It was actually John Casor, and also why Anthony Johnson was the first slave owner in the 13 colonies.

The reason why John Casor is the first slave and not John Punch. Is because While we disagree or don’t like the punishment. John Punch, was punished for a crime in that time period that he actually did commit. His two white associates who also attempted to escape from their indentured servitude owner along with John Punch. Received vastly lighter sentences, while John Punch was punished harshly with life time indentured servitude. And was recognized by the court as a Indentured servant.

Unlike in John Casor’s case, where he did not commit any crime whatsoever was legally recognized as Anthony Johnsons property by the court in the 1654 Johnson V. Parker Suit. It was John Casor’s case not John Punchs that set the precedent of slavery in the 13 colonies.

While there are quite a few who like to argue that John Punch was the first slave. But this is often to diminish the involvement of African Americans in the development of slavery in the 13 colonies. To increase the culpability of white Americans in slavery. And to paint a wrong picture that solely white people are to blame for Slavery in the 13 colonies and the future America. When in reality that is not the case.

Slavery was abolished in Mauritania in 1981, not 2007.

Wow. Your article is full of half truths and outright omissions that render it useless and distorted. For instance, you mention John Punch as the first slave but completely omit the first slave owner. I’ll help you out with that. It was Hugh Gwyn, a White man. You purposely omit that in order to plant the idea that it was a Black man, Anthony Johnson. This glaring and deliberate omission exemplifies your actual agenda. Also America was no pioneer in ending slavery. Great Britain beat you handily in that endeavor.

White lies don’t matter.

So you think black came to this country as independent contractors? I thought America became a country in 1776 not 1655?

I see us as having a seemless history with a transition from a cohesive group of British colonies to an independent country. The status at 1776, of course, is path dependent on the history prior to that pount.

“1619 was not, in stfact, the date of the first African slaves in the English colonies — those Africans were brought in under indenturement contracts, not bought as slaves. They were contracted to a fixed period of labor (typically five years) to pay for the cost charged by the Dutch slavers, at which point they were freed with a payment of a start-up endowment.”

According to the Library of Va, the first Africans were slaves. They left their country on a slave ship called the “São João Bautista” bound for Mexico. The slave was intercepted by the White Lion. Crew of the White Lion, seized and sold off the cargo; slaves to English colonies.

This is very well documented and I’m surprised you didn’t know this fact.

Source: Library of Va

They were not sold as slaves to the colonists, but rather signed off on indenturement contracts. There is a very real legal difference – an indenturement contract was a contract to provide labor for a specific time period (much like the contract signed by a pro athlete), with compensation in terms of support and a capital endowment at the end of the contract. The only loss of freedom is in terms of obligating oneself to a period of labor, and the purchaser buys only the right to the labor, not the individual.

Slavery, in contrast, denies the rights of the individual, who becomes a completely owned property of the purchaser.

That is a key difference – whether the purchaser buys a contract for services from an individual or the individual themselves.

Dear Cat. I am very interested in your reaction because it is so contrary to my own. I read the revised version of this article (post October 10th) and as a full professor of History I did not find anything obviously faulty in Avery’s factual assertions, or his logical conclusions drawn from them.

Of course, I typically publish in the fields of American intellectual history and 20th century social policy and it is entirely possible that I do not know all the facts as you apparently know them. Since I do teach this subject, I would be appreciative if you could specifically identify those “half truths and outright omissions” that you believe undermine the strength of this article. If I am laboring under some gross factual misrepresentations, I would be sincerely indebted to you if you could point to specific factual errors.

I am not unaware that you already explained that John Punch was owned by a white man, and that Avery did not mention it. That does not actually undermine Avery’s assertion that John Punch arrived in the American colonies as an indentured servant, nor does it refute Avery’s description of Anthony Johnson as a black man who was also a land owner and a slave owner. Of course, when I read the article I never assumed that Anthony Johnson owned John Punch, and Avery never asserted or intimated that connection, so I found your criticism on that score a little confusing.

Nevertheless, I am happy to recognize other factual errors that I may have missed. Please specific all the half-truths and omissions that you apparently identified. It would also help if you could provide the primary sources that you used as your authority for your criticism. That would help me greatly toward correcting my current belief that Avery summarizes a well supported position in this brief article.

Thanks,

Aharon Zorea, PhD

Professor of History

University of Wisconsin

Dr. Zhorea

I appreciate your kind comments and defense. Thanks!

My first publication, an examination of the politics of secession in Ouachita County, AR in 1860-1, was originally prepared for a graduate seminar at Purdue taught by a Wisconsin PhD alum in history, Robert May.

Thanks Again,

George Avery, PhD, MPA

Apples and oranges. And as a Full Professor at U of WI, we should expect better. Much better. The first indentured servants came to the colonies shortly after 1600. They were European white, skilled and unskilled, escaping a dismal Esperanto economy. Their terms of service were from 5-7 years, which could be extended as punishment for a variety of infractions, and working conditions could be harsh. But if they fulfilled their service, they could walk away with money and land and maybe a skill.

The first blacks came in 1619. They were brought involuntarily and initially treated as indentured servants because no slave laws existed. Of course, this quickly changed.

Avery is engaging in the sleight of hand one might see from a ten year old handling his first deck of cards. It would be amusing we’re it not a racist trope conservatives have been trying to sell since the Reagan era. VA, under a GOP Governor, wanted to change school texts to omit slavery and teach blacks came willingly to help build America.

Many thanks goes to George Avery for writing a factual account of slavery in America. Most Americans who are grounded in reality, will agree that Marxists have bet on the wrong horse, when they chose African Americans as their pet project to garner more mileage out from the traditional duo of guilt & shame. Two of the most poignant emotions, which they rely on to produce hate, discontent and a communist state. Black behavior has probably caused baleful results for leftists, who have sadly misjudged their imagined allies. Thanks again, and kind regards. Keep writing the truth! d. t. hughes

Dr. Avery,

Thank you for this informative (and much-needed) corrective account. There is, however, one mistake in your own account. The US Constitution did not ban the slave trade beginning in 1808. What the Article I, section 9 clause did was to empower Congress to ban the trade, which Congress did, at the behest of President Jefferson, at the earliest permissible date.

Thanks for the thoughtful comment. You got me on this one…the intent was the same, but I missed the detail.

That’s FAR from the only ‘error.’ It reads like Fractured Fairy Tales.

Thanks!

The error is entirely my own. You are correct that it did not ban it outright, although the intent was to serve as a compromise between the newer plantation states and those that wanted it banned outright, with the understanding that it was only a delay in an inevitable ban. The issue does, however, support my larger argument that the story of slavery is not the black-and-white portrayal in the Times articles, but rather a more complex and interesting story of how the conflict between ideals and the economics of slave labor evolved.

The Times use of 1619 is wrong for another reason: Native Americans had been engaged in holding slaves for centuries before Columbus set foot on North American soil.

But then again, if you come from a mindset that papers over the sins of dark skinned people who practice slavery in the current era, maybe it really doesn’t matter.

There seems to be an internationally orchestrated movement to falsify history and exploit White-Christian guilt to present the USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia as illegitimate “settler states”, responsible for genocide and slavery, and the UK, France, Denmark, Germany, Italy and other west European countries, as illegitimate beneficiaries of slavery, colonialism, apartheid and/or genocide. This is a form of racist collectivism, but “only white[skin]s can be racist” because we are ipso facto privileged. It serves the purpose of undermining our national sovereignty and identity, and establishing a false case for “reparations” to and “immigration” by peoples “of color”. There are white people who from various motives collaborate with or even direct this process.

Autre temps, autre moeurs.

The NYT also neglects to mention how horrific working conditions in the North often were. Something like half of early telephone linemen were electrocuted on the job, railroad workers were routinely run over by trains or killed by exploding boilers, and construction workers routinely fell to their deaths. Etc….

What you mentioned is due to lack of technology. It is no way a reflection on employers. I would be willing to bet that you believe that OSHA is responsible for the decline of injury rates in the U.S., but you would be wrong. Technology is responsible for the decline in injury rates. Employers have always been looking to decrease injuries as they are counter productive to their bottom line.

You remind me of a point I used to make to my public health students – I showed them a graph of the decline of infectious disease mortality in the 20th century with markers indicating vaccine introductions and antibiotic availability. Almost all of the reduction occurred BEFORE the availability of medical interventions – infectious disease mortality fell due to economic improvements, food safety innovations, chlorination of drinking water, and measures taken to reduce exposure to vector-borne diseases like malaria. Medical care had almost nothing to do with reducing infectious disease deaths.

I was raised in the largest toxic waste site in the US. It closure had nothing to do with technology. The government simply made them stop lying about the hazard. I’m not a big fun of OSHA and I don’t think they had much to do with making things safer for workers, but capitalism and government becoming more neutral in its labor relations caused improvements for the working man.

Mark Perry –

I graduated high school in a town with a Superfund site, and lived there for 10 years while working for the state of Arkansas. My parents’ home was about 6 houses down the street. The biggest opposition to the clean-up came from Greens.

OSHA’s primary purpose is to set standards and to ensure they’re enforced because history has shown that companies will cut corners if not monitored. OSHA is not tasked with developing safer equipment. The failure to prosecute companies and businesses for not complying with regulations is almost always due to the bureaucracy in place because no one wants to upset business.

Mr. Avery,

thank you very much for such a clear exposition of the Truth regarding Slavery in America. We need more voices like your own, to stand up against the neo-Marxist left who constantly use Race to foment division and strife between Americans.

It’s high time the American Black community turned away from the Sharptons, Jacksons, and Cummings of their current, so-called “leadership” and looked instead to the American leadership (yes, I’ve purposely left the almost ubiquitous “African” hyphenation out) for guidance.

Men like Thomas Sowell, Clarence Thomas, Walter Williams. Examples like Dr. Ben Carson. Warrior/Leaders like Col. Allen West. And especially, the new young leaders like the incomparable Candace Owens.

All these aforementioned persons are NOT hyphenated-Americans; they are Americans! They love this country, THEIR country, as do you and I. They love Truth, the Constitution, and the great, unique exceptionalism that marks the American Spirit, and that comes not from the left’s paean to diversity and multiculturalism, but from the core values which as a child, I remember we Americans strove for. As Americans, not as members of subdivisions based on class, color, creed.

With men and women such as these, I have hope that the constant onslaught by the left against all that is good in America — the banging of the drum for reparations, for re-branding of America’s past, for constantly “keeping Whitey on the Hook”, that serves the hate-America left’s goal to keep us divided — will one day be turned back, defeated, and destroyed. I see the tide turning against the left, Mr. Avery, and your article adds to that sense of hope!

En Libertad,

Coguard / Trumbull CT

Very well written and scholarly. The NYT simpleton story is a disgrace to human intelligence.

Thanks. That was my intended point – that while slavery was an undoubted evil, its role in US history is much more complicated and painted with shades of grey than the simplistic black and white political sound bite that they try to portray. This is not a defense of slavery, but a call for a an examination with open eyes and open minds of both the good and evil in history.

Bravo. Thank you for emphasis on the ideas of the Enlightenment, Glorious Revolution and revivals for the background of the American Revolution and English Government and the impact on the institution of slavery. Also Wilberforce and the Abolitionists made slavery a moral issue instead of just an economic or political one.

The current moral revisionists of history should be celebrating the moral changes that occurred in the US and England that have lead the world in the past 400 years. Instead they bemoan the fact that our ancestors were not morally pure by today’s standards. Humans are never good at moral purity and any expectation of such is a fantasy.

Exactly my point! Thanks for the kind comments.

the new York times version the of slave trade will always be whatever suits the new York times political agenda. never expect the truth from a communist, a people that don’t even believe in the concept of truth.

what happen to the story saying that Dutch ship with African people on board was boarded by privateers. The Africans were then “sold” to the Virginians (paid for with food).

Another story is the first slaves were brought here by the Spanish over 100 years prior to 1619

I’d like to read what a real History guy has to say on the matter

Not my first history work – I published a paper in a journal 25 years ago on the politics of Ouachita County, Arkansas in the secession crisis of 1860-1861 (the county population consisted of almost 40% slaves and was a center of cotton commerce in the Red River Valley, but voted Unionist), have done a number of talks at meetings on the way that Union Army medical reforms in the Civil War were diffused to the civilian world and modernized healthcare, published a book chapter on how Kaiser-type HMOs played a role in 20th century health policy development, and also published some work on military medical civic action that did a historical review of the implementation and effectiveness of such programs.

Regarding the US Civil War, in the 1980’s I saw a documentary on PBS about reconstructive operations done in the 1860’s on soldiers who had been wounded in the war. It showed several photographs of men before and after their operations. I don’t recall what the terms used back then were, but I doubt they called it plastic surgery.

Wow thank you for this research!

You are most welcome.

Dr. Avery, thank you for this very thoughtful article. Too many have stood back and allowed dishonest academics and activists take over the historical narrative of the nation’s founding. I served as the Historian & Curator of the Alamo for the last 23 years. I counter the white vs brown and stolen land manta by showing that what was happening in Mexico was a result of struggles set off by the Enlightenment’s promise of replacing the monarch/centralist form of government with the republic. As a historian and educator, I believe it is incumbent on me and others to make history both understandable and relevant. Thanks, again.

Dr. Bruce Winders

Thanks for the kind words. I greatly appreciate them.

This article reads as if you did not actually read the 1619 project and have a very particular axe to grind, with a very careful distortion of the actual project and a very careful distortion and presentation of the facts. To wit:

“1619 was not, in fact, the date of the first African slaves in the English colonies — those Africans were brought in under indenturement contracts, not bought as slaves. They were contracted to a fixed period of labor (typically five years) to pay for the cost charged by the Dutch slavers, at which point they were freed with a payment of a start-up endowment.”

Some factual inaccuracies and misrepresentations here. First, these 20 people were first kidnapped by Portuguese slaves and then captured by privateers (that is, as property) who were English, not Dutch. They were misrepresented as Dutch by the English colonists themselves. That they were sold under contracts of indenture–that is, kidnapped from their homes and sold against their will and forced to labor under coercive threat–does not obviate their status as slaves just because their status as slaves eventually ended. The very first essay in the 1619 project addresses this, of course, which I’d why I don’t think you bothered to read the project. But surely as a historian you could admit that the institution of slavery in the US evolved over decades as a legal, social, economic, and moral phenomenon, and that people could still be enslaved, in a colloquial sense, even if their enslavement did not meet the criteria of a legal regime that reached its final form decades later.

“Of the 10.7 million Africans who survived the ocean voyage, a mere 388,000 were shipped directly to North America.”

The word “mere” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. Not sure the value, as a historian, in characterizing the kidnapping and enslavement of hundreds of thousands of people, but it sure makes sense for an apologist or a propagandist. You could have just presented the number as a fact, or contextualized it with, say, the per capital rate of enslavement in the early US–when upwards of a fifth of the total population was enslaved. But, I suppose, it was more important to make American slavery seem less bad by characterizing it as a “mere” few hundred thousand (a number the 1619 project also discusses, but again you didn’t actually read it).

”

The Trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean African slave trade, which began by Arabs as early as the 8th Century AD, dwarfed the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and continued up to the 20th Century.”

Ditto the above. This is all true, but what’s the point of bringing this up in an article about what the 1619 project got wrong? The 1619 project was explicitly about the role that American slavery as a legal, institutional, political, economic, etc., phenomenon plays in shaping our lives still to this day, and at no point makes the strawman argument that American slavery was unique or uniquely bad. That you as a historian–who wrote your first publication on a single county in narrow slice of time–are pretending that a study of history can’t have a narrow scope, or that a consideration of American slavery is necessarily flawed without reminding everyone that other, worse slaveries existed, is particularly egregious.

“More shared that sentiment, and the first law in the European world to ban the slave trade was, in fact, the US Constitution, which in 1787 included language allowing the slave trade to be outlawed as of 1808 with the understanding that Congress would act on it at that time.”

What an odd lie. Including a provision that would allow Congress to legislate the status of the slave trade 20 years later is, in no way, a ban on the slave trade. The US constitution also, of course, such provisions as the electoral college, which Madison explicitly acknowledged as a concession to slave states to buy their support for the new constitution. That we still live with a counter-democratic institution explicitly designed to over-count the white citizens in slave-majority states is a testament to everything the 1619 project is about, of course.

“Economically, the institution of slavery, rather than develop the economy of the new nation, stunted its development.”

Not sure where anyone has argued the contrary in the 1619 project; on the contrary, this seems like…exactly the point of that work. You accuse the Times of a simplistic portrayal of the complexities of American slavery, but you don’t bother to engage the text itself at all beyond your perceptions of…the brief introductory text.

PS: you seem to read and engage with most of these comments, but the obscenely racist comment above by Danny Hamilton passes without comment from you. At least you’re thematically consistent.

Thank you for a very well written and enlightening article which lays out a difficult subject in an informative interesting read. Again I commend you and say thank you. This country needs some true history lessons. I pray this is read by many and more like it will be written. Well done.

Thank YOU for the kind comments!

Given how politically biased and fraudulent the NY Times has become, I doubt that they got anything remotely right, as all they peddle is democrat propaganda.

I am not a native born American citizens. I emmigrated to this country at the age of 27. I have always been interested in the history of this country. This article is an excellent description of the real history. Thank You

Frieda Keough

[email protected]

314-229-8720

You are most welcome. Thank you for taking the time tor read my article.

Why were White Folks in the market for people to work for them free? What were they doing in Africa in the first place.

It must be extremely difficult to face the real truth of who some of your ancestors were. The enslavement of African people in America was the worst human tragedy in human history.

What you should bring out is WHY it was changed from indentured servant to slave. The main problem was cultural. Most of the Blacks that ended their Indentured time, went back to living as they did in Africa. All the stereotypes of Blacks seem to stem from that time. The Blacks only worked when they had to, they had little feeling for property (crops in the field, chickens running loose, etc). The GOOD People could not stand these childish people. They needed someone to look after them because they couldn’t stay out of trouble on their own. So the GOOD People came up with a solution Slavery. It was a clash of cultures and the Blacks Lost. Those Black that did change their culture became members of society and prospered. The Slavery only came about because of the clash of cultures.

Have they changed from then until now? No.

You conclude this piece by saying that “The New York Times does a disservice to its readers with the 1619 Project by presenting a simplistic and misleading story of the complex role that the institution of slavery played in the history of the United States, and it largely ignores the role that the underlying values of the Anglo-Scottish Enlightenment that undergird the new nation played in ending slavery and the slave trade.”

You can fill in almost any topic for the “1619 Project” and “the institution of slavery,” and your indictment of the New York Times will remain true.

The so-called “newspaper of record” and “grey lady” has become the journal of discord and is a senescent lady.

Fantastic and obviously informed article. I learned a few new things as well.

While it is obviously our moral duty to hate the institution of slavery at all times, the current emphasis of so many on the Left in trying to tie the whole establishment and success of our government and society to that institution is obviously an error of extreme bias and power-seeking at the highest level.

Yes, we are imperfect. And, yes, our American predecessors on this land were imperfect as well. But, that is no reason to turn around, in Jacobin fashion, and pillory the entire American project that has brought our citizens and the rest of the world unprecedented benefit and the raising of the ideals of political equality (not absolute economic equality) everywhere.

Thank you – and you nailed my intentions with your comments. It is always rewarding to have readers understand what you are trying to say.